(A Partnership Between Children Watch & The Bellamy Fund)

Baba Dioum, a Senegalese forestry engineer, authored one of the greatest insights into the importance of education for conservation during a 1968 speech in New Delhi on Agricultural Development. “In the end, we will conserve only what we love, we will love only what we understand and we will understand only what we’re taught.”

1 The Project:

It is interesting and significant that two charities working to meet the needs of young people and adults in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu have independently settled upon the ideas behind school/community democracies. They are seen as the routes to actions for improving well-being in both school and community. One of these NGOs ‘Children Watch’ is working with the Irula tribal villagers in Kanchiporum, people who have been expelled from their forest heartland in the Western Ghats.

In 2021 The Bellamy Fund supported a development worker to make an assessment of how school/democracies could be established in Irula communities to create a sense of place. The idea is to develop the educational theme of animal conservation, expressed as a combination of peer educators, animators, child protection units, parent classes and children parliaments. This led to the Bellamy Fund in 2023 supporting a day out at the local zoological gardens, organised in partnership with Children Watch, where mothers and their children could begin to bond through the life of animals to create a shared sense of place.

This project, called ToTheZoo, has been initiated with 150 Irula children, aged between 10 to 16, with their mothers. They are going for a day trip to the local Arignar Anna Zoological Park in batches of 60 children and mothers each with 3 volunteers representing Children Watch. AAZP is a zoological garden located in Vandalur, in the southwestern part of Chennai. Established in 1855, it was the first public zoo in India. It is situated at a distance of 60 kms from the main Kanchipuram tribal villages.

The park has 81 enclosures and more than 170 species of mammals, birds and reptiles. The dense vegetation of the park supports about 56 species of butterfly. The children with their mothers will spend their time at the zoo from 9.00 am to 5.00 pm, the working hours and opening hours of the Zoo. They will be guided by the Children Watch volunteers and Children Watch’s Chief Functionary to get the most from their visit, applying informal or free choice learning to understand the relationships between people and animals under the threat of extinction.

Free choice learning refers to the process of individuals pursuing their own interests and learning in an informal and self-directed manner. Zoos can provide an excellent environment for free choice out of school learning because they offer a wide range of educational opportunities and experiences for visitors of all ages. The Irula groups will be encouraged to share their experience with feedback when they return to their homes in the evening. In this way a visit to the zoo enables children to self learn about animals and effectively, foster cognitive development and promote empathy and compassion for animals. In addition the group visit provides opportunities for societal bonding between children and their mothers, between children and between families. This is a general starting point for building a bottom-up democratic learning community facing up to a world deprived of animals.

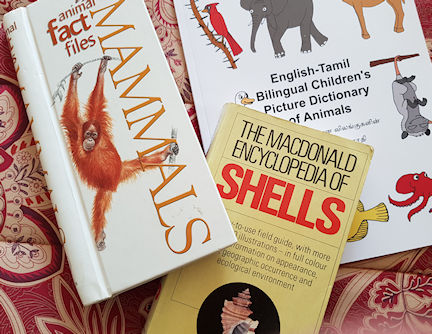

A Managing Trustee of Children Watch, with 3 volunteers, will facilitate, coordinate and implement the project activities of ToTheZoo. Volunteers, and the Managing Trustee will report on the project activities on a day to day basis and a report on the whole project will be produced by the Children Watch Team. There will be reviews to evaluate and compare the future of ToTheZoo to spark an interest in learning for its own sake. In this connection, an important learning target for ToTheZoo is to make a bilingual picture dictionary of animals.

2 The Hunter Gatherer Legacy

In 2018 Joseph Berger and Trevor Bristoe, published a paper entitled ‘Hunter-gatherer populations inform modern ecology’ which highlighted questions for understanding how humans have rapidly transitioned from a sparsely inhabited planet of hunter-gatherers to the densely populated agricultural and industrial lifestyles of today. Hunter-gatherers hunt animals in the wild. To hunt food successfully requires the application of knowledge about the human ecosystem from close day-to-day contact with wild animals as prey and the intergenerational learning of a local cultural ecology of animal behaviour. Often nomadic, this was the only way of life for humans until about 12,000 years ago when human lifestyles began to change. Groups formed permanent settlements and tended crops. Few of these tribal groups survive and those that do are well aware of the social, economic, environmental and political challenges that they are facing. They are seeking to address these challenges along with support organizations and researchers in an attempt to ensure their long-term security and well-being in biodiverse managed landscapes.

People who recently have had to define themselves as former indigenous hunter-gatherers are well placed to consider both past and present in their education systems. In this context, ‘being an animal’ is the unifying theme for successful resettlement in an industrial society, where they also have to focus on the non-hunter-gatherer societies with whom they are interacting. They must do both these things with pride in their tribal origins when they may be viewed as conservationists who coexisted closely with animals as did the whole of humanity. When humans coexist with animals, avoiding persecuting them in and around communities, they safeguard ecosystem health, agricultural stability, food security, and the creation of new sustainable economies (e.g., ecotourism). Ultimately, coexistence with animals is essential for human survival in a hot, hungry, and crowded world. Increasingly obvious are the impacts of education’s old negative attitudes towards animals as competitors. We can no longer separate humanity from nature, fail to consider long-term effects of our actions, and perpetuate conflict by indiscriminately killing wildlife. Inter-species harmony is required to sustain life on Earth in the Anthropocene, imparting what can be learned from living with animals, such as how to share and give fair treatment to others regarding compassion with moral values.

3 Societal importance of interacting with animals

Five principal categories of benefits that people may seek during a zoo visit are family togetherness, novelty seeking, enjoyment, education and escape.

Interacting with animals almost always has a positive influence on children because animals play a role in socializing and humanizing people. Many researchers and writers have noted the value of utilizing animals as mediators to help people who are not being reached by other methods. That is why everyone should have the opportunity to build their own personal body of knowledge to live sustainably. This means sharing Earth with other animals in a global network of protected sites governed by conservation management systems. The network is really a huge animal sanctuary, keeping those under threat from human activities safely until sometime in the future when they can be free. This is the essence of how modern zoos see themselves, being on a par with UNESCO biosphere reserves, oceanic fishing stocks and local nature sites. Visiting a local zoo from these perspectives can make visitors think that maybe there isn’t that much that makes us uniquely human. Maybe we need to pay more attention to what animals are doing, and try to view the world through their eyes. And, perhaps our ability to consider animal’s feelings and hope for the well-being of these other creatures is our best, and most uniquely human ability to bridge the gap between people and other animals.

Nowhere is this gap wider than in the Indian tribal Irula community of Tamil Nadu who for millenia, have had a close relationship with the forest of India’s Western Ghats. Due to forest conservation policies and environmental protection laws, these people are actual forest dwelling conservationists who have been displaced and forced to leave their homeland, becoming rootless migrants. The Irula tribe is one of the victims within this process of deforestation. As forest resources are destroyed, Irula are denied the rights to collect minor forest produce they had as as hunter gatherers, and their activities have shifted to unreliable unorganised bonded manual labour available in farming and allied activities outside the forest, such as quarrying stone, making bricks, milling rice, making charcoal, cutting wood for fuel and harvesting sugar cane. As the vast majority of Irula adults are now uneducated and illiterate it is essential for Irula children to be allowed the opportunities of a formal education. Irula parents as a community do not understand the values of education as it’s never been a part of their unsettled lives. Irula who want their children to attend school face many obstacles. The concerned authorities hesitate to provide the children with the Community Certificates to access free education boarding facilities and scholarships earmarked by law for all Scheduled Tribes in India. Therefore admission and enrolment in schools, attending examinations, moving to other levels of school and higher education is being prevented. A lack of money for uniforms, school equipment and text books as well as social discrimination within educational institutions remains a block to their participation.

Irula self-esteem and mutual respect is lost as individual and local powers develop and expand to leave no room for displaced tribal peoples. They follow tradition, keeping their few customs with them. However, there is a gradual erosion of these practices in today’s India making them even more isolated and the poorest of the poor. Hence, enrolling in schools, attending classes regularly, listening to teachers, interacting with classmates from other communities is alien to the Irula children. Under these circumstances, the Government encourages Tribes to put their children in residential schools where children will stay in hostels and attend free schools under the Scheme for Scheduled Tribes. Children in other low income castes have opportunities to travel to villages, towns, festivals and other important historical places, with hill walks, and amusement parks. In contrast the Irula are living out of touch with modernity.

Under these circumstances, ToTheZoo is working in partnership with Children Watch, a local Indian NGO, to sponsor a new kind of humanitarian aid where the local zoo becomes an education window on a wider societal development. For Irula children, an outing to the zoo will open their eyes to a new understanding of the world of animals which they can explore through guided self education to reconnect them with the workings of the Western Ghat forest, now under protection as one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet.

4 A Democratic Learning Community

A democratic learning community is one in which each member has equal opportunity to influence change and contribute to the learning environment in a real and respected way, one in which learning is understood as something that every single person is capable of doing and has the right to access. In a democratic learning community the educator is no longer the omniscient teacher, telling students what to know and how to learn it. Teachers become facilitators of daily learning,who understand the many ways in which individuals learn and value the opinions/ideas/knowledge of each learner while providing them with ample space to share that knowledge with the rest of the community. Simply put, a democratic learning community is one in which learners are educators and educators are learners. Both contribute to the educational discourse of the learning space and both share power, never yielding it to those who want to control or manipulate learning or the space in which it occurs.

5 ZooPost

ToTheZoo is about involving communities in the educational process to provide real-world opportunities to make learning more memorable and impactful. ZooPost is about using a visit to a zoo to enhance ecological awareness using words and pictures to describe the natural world and our impact on it. It becomes a resource for students to observe, feel, enjoy and communicate to others. ZooPost uses the exchange of postcards, analog or digital, to reveal an attachment with the wider world, which can increase their motivation to learn. In a time where the world feels more divided than ever, connecting children with a global community of junior zoologists holds a whole wealth of positives for their education and wellbeing. It increases their motivation in school, giving them a sense of belonging. Students can see a reason as to why they’re learning what is being taught. Zoology is the easiest of the ‘ologies’ to democratise in this way.

6 The Welsh Connection

The ideas underpinning ToTheZoo, as an exercise in conservation education have emerged in Welsh schools where the Well-being of Future Generations Act requires public bodies in Wales to think about the long-term impact of their decisions, to work better with people, communities and each other, and to alleviate the persistent problems such as poverty, health inequalities and climate change. Teachers are free to design a humanities syllabus that is relevant to the needs of their learners and communicate their ideas and achievements with ZooPost across continents.

Socialising Influences of a Zoo Visitation

https://www.mdpi.com/2673-5636/4/1/6

https://exploringdemocraticlearning.weebly.com/

https://sites.google.com/view/tothezoo/home

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00938157.2019.1578025?journalCode=grva20