Electric encounters’ with cultural heritage

“Landscape and identity are inherent components of our culture, one informing the other … access to, and freedom to enjoy the landscape as well as respect for spiritual and symbolic meanings people ascribe to their landscape, are some of the components that will support dignity and well being of communities”.

‘The Right to Landscape: Contesting Landscape and Human Rights’ – Cambridge (2008). Workshop, marking the sixtieth anniversary of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

1 An expression of cultural ecology

Academic definitions of landscape invariably encompass an area of land containing a mosaic of scenic patches. These patches are landscape elements that are discerned by eye, singly or in groups. We enter the countryside with a predisposed sense of attentiveness to make mental connections to these elements and their patterns. The discernment of visual heterogeneity is the initial response and in 1986 Forman and Godron defined landscape as a heterogeneous land area composed of a cluster of interacting ecosystems that is repeated in similar form throughout. Again stressing the importance of heterogeneity against a uniform background, Turner et al, in 2002 defined landscape as an area that is spatially heterogeneous in at least one factor of interest. To understand a landscape meaningfully therefore involves focusing on the management of factors, past or present, that produced the landscape elements. No landscape is pristine so in responding to the pictorial elements in this way we go back in human history. We pass through a sequence of historical periods each representative of the local human ecological niche at a time when the place provided an important ecosystem service for the people who had integrated their culture with its ecology.

In this broad cross-subject context it is desirable to widen the old ideas of nature, with its expressions of ‘awe’, ‘absolute’ and ‘distant from human capacities’, to a more complex and dynamic view of the reality of environment as a collection of natural processes to which are assigned human values and aesthetics. Landscape then becomes nature. Its elements are groups of ecosystems, including the human ecosystem, but there are interactions among them, which again places a cultural focus on spatial heterogeneity and the processes maintaining it, then and now.

To summarise, landscape is a universal pictorial facet of the human ecological niche linking culture with ecology, because there is now no place on Earth that humankind has not incorporated into the cultural traits of societies; their behaviours, beliefs, and symbols. In this respect, landscape has permeated the management of cultural heritage, leading in 1992 to UNESCO recognising the following three categories of cultural landscapes of outstanding universal value for world heritage listing.

(i) Landscape designed and created intentionally by man. This embraces garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons which are often (but not always) associated with religious or other monumental buildings and ensembles.

Fig 1 Duffryn Gardens: home of the Cory ‘coal owning’ family

(ii) Organically evolved landscape. This results from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. Such landscapes reflect that process of evolution in their form and component features. They fall into two sub-categories:

– a relict (or fossil) landscape is one in which an evolutionary process came to an end at some time in the past, either abruptly or over a period. Its significant distinguishing features are, however, still visible in material form.

– a continuing landscape (Fig 2) is one which retains an active social role in contemporary society closely associated with the traditional way of life, and in which the evolutionary process is still in progress. At the same time it exhibits significant material evidence of its evolution over time.

Fig 2 Griffith St, Maerdy, Rhondda Fach

(iii) Associative cultural landscape. This is defined by virtue of the powerful religious, artistic or cultural associations of the natural element rather than material cultural evidence, which may be insignificant or even absent (Fig 3).

This three part categorisation was predicated on the understanding that landscapes are the outcome of social processes at the interface of culture and nature, tangible and intangible heritage, biological and cultural diversity. In this respect they represent a closely woven net of relationships expressing the essence of culture and people’s identity.

Fig 3 St Mary’s Well, Penrhys, Rhondda Fach

The UNESCO world heritage listing inevitably devalues all landscape that are not so listed. Also the selection process is biased towards rural landscapes, which devalues the urban places where most people now live. In fact, landscapes, beautiful or ugly, urban or rural, all reflect a collective past and determine the future quality of life of the people who live there. Landscapes are about contemporary people and places. Wherever we live, they are fundamental to our health and well-being, and are an important part of our identity. It is critically important that the value of landscape is recognised in decision making locally as well as internationally.

Intimately connected with landscapes are people’s stories and the things of which memories are made. These stories make up the cultural richness that promotes a sense of local distinctiveness. Locals and visitors alike can be given a sense of participation with the past through presentation of appropriate interpretative material. Thereby people’s surroundings can be appreciated as a human right in terms of access to encourage personal fulfillment through states of mindfulness and meaningfulness.

2 Attentiveness to heritage

“I saw behind me those who had gone, and before me, those who are to come. I looked back and saw my father, and his father, and all our fathers, and in front, to see my son, and his son, and the sons upon sons beyond.- Richard Llewellyn. How Green Was My Valley

The past has always been with us, but heritage is a recent invention. The word “heritage” in its present English usage carries a complex of cultural, economic and political associations. These associations articulate social drives such as the need for a sense of connection with the past, the desire for the reassurance of identity and a sense of place which includes humankind’s dependence on nature. Richard Llewellyn took up the latter theme in his novel How Green Was My Valley;

‘The quiet troubling of the river, and the clean, washed stones, and the green all about, and the trees trying to drown their shadows, and the mountain going up and up behind, there is beautiful it was.’

Llewellyn gathered material for his novel in the 1930s from conversations with local valley mining families in Gilfach Goch, which he contrasted with an imagined pastoralism of the preindustrial wooded valleys of South Wales.

The possessive passion is universal. ‘It’s our land’, say the tenant farmers in John Steinbeck’s novel, Grapes of Wrath. ‘We measured it and broke it up. We were born on it, and we got killed on it, died on it. Even if it’s no good, it’s still ours. That’s what makes it ours — being born on it, working it, dying on it.’ Set in the US during the Great Depression, the novel focuses on a poor family of tenant farmers driven from their Oklahoma home by drought and economic hardship.

We cannot help but make contact with heritage through landscape because no matter how academics define it, our local environment is our heritage, Even when we enter a stretch of countryside for the first time in a recreational mode we define it pictorially as a scene that opens up a discourse about nature through images. The discourse starts with the visual cropping of one’s surroundings as if taking a snapshot. This isolates areas that we feel make satisfactory pictorial entities. Invariably, these pictorial entities are also cultural ones upon which we inevitably have to cogitate.

Random mental connections with landscape elements may be made through a sense of wonderment: e.g. an unexpected rainbow, a flock of birds. Usually these elements are described as beautiful expressions of nature. These have been described as ‘electric encounters’. The other reaction is a response to having prior information for interpreting the landscape and its elements that draws a person to visit it, either to reinforce personal knowledge or to amplify it.

An unexpected surprising encounter may or may not trigger a desire for information. It is akin to a state of mindfulness. The visible and invisible come together as a spiritual experience. Often, the latter response results in, or augments, a sense of meaningfulness. This characteristic relates to an individual’s sense of who they are and how they navigate their way through life. This is directly related to the answers a person has to what are traditionally thought of as life’s ultimate questions:

Who am I?

Why am I?

What is the meaning of life?

What is the meaning of my life?

These are the questions that humankind has pondered since it became self-aware and developed the capacity for critical reflection.

In chance encounters with landscape elements there seems to be a general fear of not understanding what one sees and this search for meaning often tips people away from cultivating and holding on to a sense of mindfulness. Mindfulness in this context involves accepting that we pay attention to our thoughts and feelings without judging them—without believing, for instance, that there’s a “right” or “wrong” way to think or feel in a given moment. When we practice mindfulness, our thoughts tune into what we are sensing in the present moment rather than rehearsing the past or imagining the future. For there to be a shift from mindfulness to meaningfulness there has to be a quest for information about the past and future.

Although a state of mindfulness may be triggered by a natural phenomenon it can be induced by a man-made object that is an element of the landscape whose purpose is unknown. For example, “applied art” refers to the application (and resulting product) of artistic design to utilitarian objects in everyday use. Whereas works of fine art have no function other than providing aesthetic or intellectual stimulation to the viewer, works of applied art are usually functional objects which have been “prettified” or creatively designed with both aesthetics and function in mind. Applied art embraces a huge range of products and items, from a teapot or chair, to the walls and roof of a railway station or concert hall, a fountain pen or computer mouse. For the sake of simplicity, works of applied art comprise two different types: standard machine-made products, which have had a particular design applied to them to make them more attractive and easy-to-use; and individual, aesthetically pleasing but mostly functional, craft products made by artisans or skilled workers. Applied art is a feature of landscape heritage,which is often exemplified by a piece of left-behind applied art that is slowly decaying (Fig 4) . In this connection architecture, too, is best viewed as an applied art.

Fig 4 A piece of unlabelled mining machinery: Rhondda Heritage Centre, Trehafod

3 Access and interpretation

“How can there be fury felt for things that are gone to dust.”

-Richard Llewellyn, ‘How Green Was My Valley’

As people increasingly seek out meaningful activities in the outdoors, heritage conservation seeks an every increasing grip on scarce public finances. Questions are being asked about the purpose of heritage sites. A central question is how can people use heritage sites to seek and maintain meaningful lives. This has been taken up by the Dutch nature conservation organisation Staatsbosbeheer (National Forestry Service) which discovered that its constituents are increasingly seeking out meaningful activities in nature. However, the focus is not on the ultimate meaning of human life but rather on what are the conditions in which a person experiences that his or her life is meaningful? In other words, there is a process of self searching about how he or she feels that life is fulfilled by meaning. The search for meaning in life or for meaningful nature experience, requires some kind of meaningful activity as a prerequisite. But what is actually considered a meaningful activity in nature? What do people consider to be meaningful and how are these questions to be addressed by organisations involved with heritage conservation?

Opening up access and the interpretation of what there is to see are integral parts of an overall landscape management plan. Virtually every management decision has a direct or indirect impact on these two goals. Interpretation of the site must include its social and historical significance: which social groups built the site? What were their links with the surrounding countryside? What materials, know-how and techniques did they use? In what historical conditions was it built? What were the economic, aesthetic or strategic purposes of the site? What problems were encountered when it was being built? etc. These are some of the questions interpretation must answer, and which the management of the site must be designed to elicit.

Access and interpretation of any aspect of landscape as heritage should motivate the visitor to assist in conserving it. This is expressed in the U.S. National Park Service formulation of visitor interaction as a linear process. “Through interpretation, understanding; through understanding, appreciation; through appreciation, protection”.

Regarding the benefits of heritage conservation, which also includes nature conservation, the following quotations about interpretation from UK conservation management exemplify the positive approach which is needed on the ground.

Firstly from Michael Hughes: “For many years Oxwich National Nature Reserve was perceived as a fragile site in need of a tightly controlled access policy. In the early eighties however, we recognised the inherent robustness of the reserve and much of the dunes, woodlands and marshes became open access”

Secondly, from Dan Hillier, on wildlife tourism: “The long term aim should be to make watching wildlife a small element of as many people’s holidays as possible”.

Finally two quotes from Richard Sharland, on the approach of the UK Wildlife Trusts:

(1) “Discovering the importance of the wider public has meant creating more access to sites of wildlife importance, so that people can realise the significance of their heritage through direct experience”.

(2) “The awareness generated by interpretation is also recognised as having importance in its own right. If people know more about their local wildlife, their quality of life is enhanced, they will make better citizens, they will have a better understanding of the world and their responsibilities within it”. These comments refer to wildlife conservation but they can also be applied to all kinds of landscape elements.

4 Benefits as management outcomes

Before public access can be properly assessed and desirable outcomes turned into measurable management objectives, heritage landscapes must first be recognized as indispensable to our own well being. People have been discussing their profound experiences in nature for the last several 100 years—from Thoreau to John Muir and many other writers. Now we are seeing changes in the brain and changes in the body that suggest we are physically and mentally more healthy when we are interacting with nature.

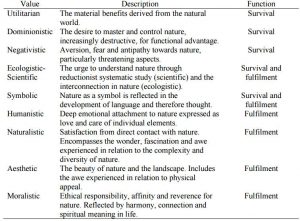

The fundamental aim of a landscape management plan is to develop connections between the visitor/observer and then obtain feedback on the way the landscape was valued and utilised mentally and physically, once a connection was made. In their study of the psychological rewards from nature connectedness Miles Richardson and Jenny Hallam related values and functions of biophilia to the psychological rewards of engaging with the natural world. The rewards cover aspects such as restoration, personal growth, creativity and inspiration. For example, there are reports of the amazing feelings of happiness and inner calm of being close to nature. Similarly, self-reports of nature connectedness, which included a wide range of descriptions, including calmness, wholeness, wonder and peacefulness. These responses are included in Kellert’s nine values of biophilia (Table 1).

Table 1 Kellert’s nine values of biophilia

However, this research relates to interaction with ecosystems and the value of relating to human heritage artifacts was not examined.

Nevertheless it has a bearing on the move by some educationalists to replace the traditional goals of knowledge and understanding with personal and social objectives concerned with enhancing and developing confidence and self-esteem in learners. In this connection, Terry Hyland believes that the concept of ‘mindfulness’ can be an immensely powerful and valuable notion. This is because it is integrally connected with the centrally transformative and developmental nature of learning and educational activity at all levels. For example, Wordsworth was in a state of mindfulness when he wrote the following poetic lines, the outcome of contemplating the landscape of the dramatic limestone gorge of the River Wye above Tintern Abbey.

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of the setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man:

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of thought,

And rolls through all things.

In a mood of secular spiritualism, Wordsworth looks beyond surface appearance to gain insight into a deeper level of existence. which fuses mind and nature in a living whole.

5 The Rhondda Fach model

Rhondda, or the Rhondda Valley, is a former coal mining valley in South Wales consisting of sixteen pit-head communities that settled along the course of the River Rhondda during the 19th century. The area is, in fact, made up of two valleys: those of the larger Rhondda Fawr valley (Welch: mawr = large) and the smaller Rhondda Fach valley to the East (Welch: bach = small). The latter valley has been selected for modelling people’s interactions with landscape heritage because of its relatively small size and because it represents a semi rural cultural landscape densely packed with scenic heritage, from prehistoric times to the post industrial period. A skeleton management plan targeting mindfulness is structured according to the following logic.

Vision

Residents and visitors as individuals and groups interacting with the visual elements of landscape heritage using maps and interpretation material, cogitating on what they discover. Then uploading pictures with comments describing their feelings, relating the experience to their place in a grand scheme of things.

Objective:

The objective is to involve residents and visitors in highlighting their personal selection of landscape heritage elements, with their reasons for selecting them, online.

Rationale:

Informed by community heritage values, the rationale of the plan is to encourage the uptake of William Wordsworth’s view of landscape beyond its surface appearance. Thus, residents seek important landscape elements that are representative of their identity. Visitors investigate heritage pertaining to the character of local communities through which they pass. The elements and commentaries will have beneficial outcomes for residents and visitors alike. They will help people utilise landscape as an ecosystem service to to interpret outdoor experiences, probe identities, interrogate cultural/urban assumptions and understand historical, social, economic and political contexts. In these respects these outcomes will become an important stakeholder input to local plans for conserving landscape heritage as a facet of sustainable development..

Methodology:

The methodology will show how landscape elements can be selected for online display and viewer interaction that have contemporary historic/cultural significance in the minds of residents and visitors. A freely accessible community IT system for interaction and display will be used.

Outcome:

The outcome is the inculcation of environmental awareness down to the deepest levels of mindfulness and meaningfulness that can be displayed online through personal creativity with pictures, poetry, fable, myth and story.

The planning procedure is based on the following sequence of actions:

1 Map an inventory of heritage landscapes.

2 Define access routes

3 Provide interpretive material.

4 Define the barriers preventing the establishment of 1-3.

5 Scedule work has to be done to overcome the barriers.

6 Monitor progress 1-5 with performance indicators.

7 Monitor the outcomes using site statistics to assess the level of meaningfulness..

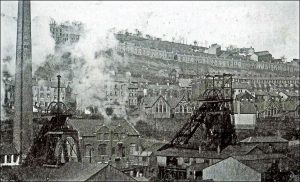

Fig 5 Installation (2016) commemorating Tylorstown Pits 8 (Cynllwyn-Du) and 9.

Fig 6 Pits 8 and 9 (early 20th century) and the Tylorstown community that served them.

This Rhondda Fach model is being developed further at:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mGq-xRgE6VLlbwRUyNGktrt_G32dYdAefsq4eRszEjY/edit?usp=sharing

5 References

http://sprite.bolton.ac.uk/186/1/ed_journals-13.pdf

http://eyes4earth.org/2015/07/the-search-for-meaning-in-life-what-can-nature-conservation-do/

Emrys Pride, Rhondda My Valley Brave (Stirling Press,

1975) 942.972 PRI

E D Lewis, The Rhondda Valleys (Phoenix House 1959)

942.972 LEW

John and Norah Morgans, Journey of a LIfetime (John and Norah Morgans 2008)

Appendix

Life by Numbers

Celebrating the Deaths of Heroes

1 Foreword

One of 2 tributaries of the Rhondda River.

No.1 colliery of the Ferndale group,

Alias Blaenllechau Farm,

First of 9 pits in the Ferndale cluster

2 The Heroes

Here in the slowly regreening valley of the Little Rhondda,

Contemplating an artistic tram brimming with coal,

We focus costing the black gold

And the wealth promised by a grocer,

David Davis of Blaengwawr,

Sinker of Ferndale Pit No 1 in 1857.

Penetrating with scientificl hope

Deep into the unprofitable wildness

Of pastoral bracken

With its own money-making plant lore

For farmers:

Under gorse – copper.

Under brambles – silver.

Under fern – gold.

Day 6 of the week dated 8-11-1867.

2 consecutive explosions.

With Christian hope

It took a month of long days to recover

The unidentifiable remains of 178 men,

And an unknown number of dead horses.

Blame:

Subheading 1

An unmeasurable accumulation of gas,

Due to the neglect of the manager,

And inaction

Of an unrecorded number of colliery officers.

Blame:

Subheading 2

Gas fired by 1 or more of the colliers

Carelessly taking off the tops of their lamps

To work with naked lights.

Tylorstown

17 months later 10-6-1869

No 9 colliery of the Ferndale group

Companion to Ferndale No 8

Alias Cynllwyn-Du, in a pastoral past.

Another killing recorded as 53 men and boys.

Blame:

Subheading 1

Managers ignored recommendations after 1867.

Blame

Subheading 2

Failure of the pit’s fresh air ventilation system.

3 A Final reckoning

Pit No 8 provided 77 years of employment

Pit No 9 provided 53 years of employment

1913: Peak coal output from South Wales;

56 million tons.

Or, to put it another way,

127.000 tons were won per miner killed

That year.

Coal is long dead,

Hope is now a political commodity.

4 Postscript

No 5 pit 13-2-1908,

Here is

55-year-old former Private

Thomas Chester,

An uncrossed hero,

Who 29 years earlier,

Helped forge an Empire.

At Rorke’s Drift

Where rifles enriched by Rhondda coal,

Killed Zulu warriors,

Thrusting spears and leather shields,

Thomas is working in the washery,

Trimming coal,

He allows two wagons to pass,

Then steps onto the tracks

Leading to No.1 pit screens,

To break up a lump of coal,

Fallen by chance onto the empty

road.

He is crushed to death by a wagon,

Being lowered towards the screens,

Unaware that other wagons were to follow.