Ecosystem services and conservation management

“Here and there on the green plush surface of the moss were scattered faint circular marks, each the size of a shilling. So faint were they that it was only from certain angles that they were noticeable at all I wondered idly what could have made them. They were too irregular, too scattered to be the prints of some beast, and what was it that would walk up an almost vertical bank in such a haphazard manner? Besides, they were not like imprints. I prodded the edge of one of these circles with a piece of grass. It remained unmoved and I began to think the mark was caused by some curious way in which the moss grew. I probed again more vigorously, and suddenly my stomach gave a clutch of tremendous excitement. It was as though my grass-stalk had found a hidden spring, for the whole circle lifted up like a trap door. As I stared, I saw to my amazement that it was in fact a trap door, lined with silk, and with a neatly bevelled edge that fitted snugly into the mouth of the silk lined shaft it concealed. The edge of the door was fastened to the lip of the tunnel by a small flap of silk acts as the hinge. I gazed at this magnificent piece of workmanship and wondered what on earth could have made it”.

Gerald Durrell-as a boy partaking of cultural ecosystem services in wonderment..

1 Background

During the past decade there has been a global move towards holistic conservation management, with integrated plans for local ecosystem services (Fig 1) taken down to the level of the family and its neighbourhood. This is a practical approach to cultural ecology because such plans involve modelling the ecocultural dynamics of the local human ecological niche which encapsulates the dependence of humankind bonding with other creatures.. We now have to legislate to establish and maintain this vital relationship

Fig 1 Classification of ecosystem services

Two significant moves in this direction are the Future Generations (Wales) Act, recently introduced by the Welsh Government, and Section 38 of Kenya’s Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) Both initiatives demand that local government, in partnership with its communities, should co-produce plans for the well-being of future generations. In Wales these plans are called ‘well-being plans’ and in Kenya they are ‘district environment action plans (DEAPs)’. Regarding the format for such plans, a good Kenyan example is the Mount Elgon DEAP. Wales has yet to specify the required format of its well being plans.

The two systems of legislation have arisen independently as frameworks within which local government is required to make statutory conservation management systems to ensure the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (the sustainable development principle).

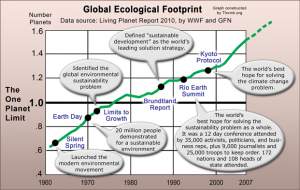

The plans will have to operate seamlessly from strategic to operational levels and manage the linkages between fragmented ecosystems and the interconnections amongst cultural practices, economic development, environmental stressors, ecosystem attributes and restoration activities for impacts on biodiversity, locally and globally into day living. Performance indicators for well being are required so that everyone can check out progress of their local plan to see how far their global footprint is from the ‘one planet limit’ (Fig 2).

Fig 2 The historic milestones in the hope for sustainability

2 Purpose

The starting point for managing ecosystem services is for people to have some sort of awareness of their local ecological assets and the importance of managing biodiversity for human well being.. This blog explores a knowledge system for assembling conceptual management models so that people can make contact with other living things in a managed ecological context, be it a potted plant, a private garden, trees in the street, parks, a pathway through the countryside, a zoo/wildlife park and large scale terrestrial, marine, and freshwater protected areas.

The early conservation movement included the protective management of fisheries, wildlife, water, soil and sustainable forestry. The contemporary movement has broadened from an emphasis on use of sustainable yields of natural resources and preservation of wilderness areas to include preservation of life in all its diversity. Conservation has come to define a management system that aims to preserve natural resources expressly for their continued sustainable use by humans as an intrinsic good and a contributor to human well being and survival.

Over time, large scale protected areas have moved from being places of physical isolation, where management was frequently hands-off or laissez-faire, to places where active restoration is done to restore biodiversity and other valuable features of the protected area. Although protected area management aims first at protecting existing ecosystems, a combination of previous degradation and continuing external pressures mean that restoration has become the norm for conservation management. This is because, on an overcrowded planet, ecosystems are no longer a pristine state in which humankind evolved and continuous management is needed to restore them to a past condition of low human impact. In recognition of this global situation the term ‘restoration for protected areas’ has been introduced by the IUCN for activities within protected sites and for activities in the wider system of connecting or surrounding lands and waters that influence protected area features. Sometimes a conservation plan necessitates restoration beyond protected area borders (e.g. to address ecosystem fragmentation and maintain well-connected protected area systems).

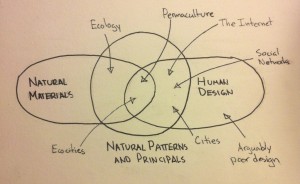

Fig 3 The human niche as the outcome of social design

Humans have a long history of niche construction—of modifying their environments, large and small by designed behaviour patterns that are both deliberate and inadvertent (Fig 3). Although the consequences of human niche construction in this way are not always anticipated, one of the primary goals of environmental engineering by human societies has been to increase their share of the annual productivity of the ecosystems they occupy by increasing both the abundance and reliability of the plant and animal resources they rely on for food and raw materials. Using fire and simple technology in the modification of vegetation communities, our distant ancestors were shaping environments more to their liking in ways that we can see in the archaeological record back perhaps as far as 40 000 years ago. The recent shift towards holistic management involves the integration of ecosystem services and conceptual models of conservation management should work within the socio-cultural characteristics of the local human ecological niche. As syntheses of the state of understanding of the dynamics of the human niche, conceptual models of ecosystem services can provide a basis for examining the potential risks and consequences of various restoration options and related actions. Modelled attributes of the restored ecosystem can also be used as benchmarks for evaluating the success of various stages of the management project and determining the need to change restoration actions or policies through an adaptive approach. Descriptions of the abiotic and biotic attributes of one or more sets of reference ecosystems are important contributors to conceptual models for ecological restoration projects. Mind maps are essential to visualise these complex models at a glance.

3 Definitions

Ecological restoration: ‘the process of assisting the recovery of an ecosystem that has been degraded, damaged, or destroyed’ (SER, 2004)

Protected area: ‘A clearly defined geographical space, recognized dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated human ecosystem services and cultural values’

4 Restoration

■■ Restoration in and around protected areas contributes to many societal goals and objectives associated with biodiversity conservation and human well-being, Indeed, holistic restoration management can be thought of as a wellbeing plan.

■■ Reasons for implementing restoration projects vary and may include, for example, recovery of individual species, the strengthening of landscape or seascape-scale ecosystem function or connectivity, improvement of visitor experience opportunities, or the re-establishment or enhancement of various ecosystem services

■■ Restoration can contribute to climate change adaptation by strengthening resilience to change and providing ecosystem services. It can contribute to climate change mitigation by capturing carbon in ecosystems

■■ Rapid climate change and other global changes create additional challenges for restoration and underscore the need for adaptive management

■■ Protected area managers need to work with stakeholders and partners inside and outside protected area boundaries to ensure successful restoration within and between protected areas

5 Operating Principles

Re-establish values

Effective ecological restoration for protected areas is restoration that re-establishes and maintains the values of a protected area

- ‘Do no harm’ when restoration is the best option

- Re-establish ecosystem structure, function and composition

- Maximize the contribution of restoration actions to enhancing resilience even when this may need changed objectives (e.g., to climate change)

- Restore connectivity within and beyond the boundaries of protected areas

- Encourage and re-establish traditional cultural values and practices that contribute to the ecological, social and cultural sustainability of the protected area and its surroundings

- Use research and monitoring, including from traditional ecological knowledge, to maximize restoration success

Maximise beneficial outcomes

Efficient ecological restoration for protected areas is restoration that maximizes beneficial outcomes while minimizing costs in time, resources and effort

- Consider restoration goals and objectives from system-wide to local scales

- Ensure long-term capacity and support for maintenance and monitoring of restoration

- Enhance natural capital and ecosystem services from protected areas while contributing to nature conservation goals

- Contribute to sustainable livelihoods for indigenous peoples and local communities dependent on the protected areas

- Integrate and coordinate with international development policies and programming.

Engage with others

Engaging ecological restoration for protected areas is restoration that collaborates with partners and stakeholders, promotes participation and enhances visitor experience

- Collaborate with indigenous and local communities, neighbouring landowners, corporations, scientists and other partners and stakeholders in planning, implementation, and evaluation

- Learn collaboratively and build capacity in support of continued engagement in ecological restoration initiatives

- Communicate effectively to support the overall ecological restoration process

- Provide rich experiential opportunities, through ecological restoration and as a result of restoration, that encourage a sense of connection with and stewardship of protected areas

6 Planning principles

Identify valued features

- These will usually be habitats and species but can also be ancillary systems, such as the facilities for access and visitor education,

Factor analysis

- Identify all major factors, sometimes called ‘barriers’, causing degradation—undertaking restoration without tackling underlying causes is likely to be fruitless.

- Identify and where possible control external factors such as pollution that may compromise restoration efforts

- Restore, where possible, ecosystem functioning along with physicochemical conditions and hydrology

- Consider natural capital, ecosystem services, disaster risk reduction and climate change mitigation and adaptation

- Identify potential negative impacts of the restoration programme and take action to limit or mitigate them as much as possible

- Assess the possible impacts of climate change and other large-scale changes on the feasibility and durability of restoration and try to build resilience through adaptive planning

- Establish a rationale to manage each factor through researching how it impacts on the feature.

Participation

- Ensure a participatory process involving all relevant stakeholders and partners in planning and implementation, facilitating participation and shared learning, contributing to acquisition of transferable knowledge, improving visitor experiences, and celebrating successes.

Objectives

- Set clear restoration objectives for the state of each feature—it may not be appropriate to aim for a ‘pristine’ or ‘pre-disturbance’ state, particularly under conditions of rapid environmental (e.g., climate) change

- Recognize that some objectives or motivations for restoration may conflict and work collaboratively to prioritize among them

Scheduling

- Ensure that the time frames for the activities required to meet the objectives are clear

Monitoring

- Ensure that monitoring addresses the full range of restoration objectives and the intermediate stages needed to reach them

- Use monitoring results and other feedback to adapt the plan according to the outcomes

7 A Welsh model

The Well-Being of Future Generations Act

http://gov.wales/about/cabinet/cabinetstatements/2014/8995356/?lang=en

Fig 4 A well being hierarchy of human needs

The Act provides for a set of long-term well-being goals for Wales within the context of a hierarchy of human needs. (Fig 4). These goals set for a prosperous; resilient; healthier; more equal Wales; with cohesive communities; and a vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language. Placing them in legislation will provide a clear definition of a sustainable Wales, and help deliver the long term consistency and certainty that is needed to tackle future challenges, for example climate change, tackling poverty, and health inequalities.

The Act will require Welsh Ministers to establish national indicators to measure progress towards the achievement of the well-being goals and report on them annually.

About the Act

The key purposes of the Act are to:

- set a framework within which specified Welsh public authorities will seek to ensure the needs of the present are met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (the sustainable development principle),

- put into place well-being goals which those authorities are to seek to achieve in order to improve wellbeing both now and in the future,

- set out how those authorities are to show they are working towards the well-being goals,

- put Public Services Boards and local well-being plans on a statutory basis and, in doing so, simplify current requirements as regards integrated community planning, and

- establish a Future Generations Commissioner for Wales to be an advocate for future generations who will advise and support Welsh public authorities in carrying out their duties under the Bill.

The Act sets out six well-being goals against which every public body must set and publish well-being objectives that are designed to maximise its contribution to the achievement of the well-being goals. The Well-being goals are:

- A prosperous Wales

- A resilient Wales

- A healthier Wales

- A more equal Wales

- A Wales of cohesive communities

- A Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language

Sustainability is at the forefront of the Bill and it seeks to ensure that the long term effects of current decision making are considered at all times. It will, if passed (it has the backing of all political parties), formalise partnerships across the public sector to ensure a joined up approach to delivery and planning. In applying the sustainable development principle the Bill requires that public bodies take into account:

- The importance of balancing short term needs with the need to safeguard the ability to meet long term needs

- The benefits of taking an integrated approach by considering how: an objective may impact upon each of the well-being goals and the social, economic and environmental aspects and; the impact of the body’s objectives on each other and upon other public bodies’ objectives.

- The importance of involving those with an interest in the objectives, seeking views and taking them into account

- How collaborating with any other person could assist the body to meet its objectives, or assist another body to meet its objectives.

- How deploying resources to prevent problems occurring or getting worse may contribute to meeting the body’s objective, or another body’s objectives

There must be a Public Services Board for each local authority area in Wales. The board will include the Local Authority, Local Health Board, the Welsh Fire and Rescue Authority and Natural Resources Wales as statutory members. In addition the board must invite (‘invited participants’) the Welsh Ministers, the Chief Constable of the police force in that area, the Police and Crime Commissioner, a person required to provide probation services in relation to the Local Authority area and a body representing voluntary organisations in the area. Other relevant organisations can also be invited to join the board.

The aim of the Public Services Board will be to improve the economic, social and environmental well-being of its area in accordance with the sustainable development principle. Each board is required to publish an assessment of the state of the economic, social and environmental well-being in its area prior to the production of a local well-being plan. This is similar to current arrangements for Local Service Boards and the existing practice of undertaking needs assessments and producing a Single Integrated Plan but will be a statutory requirement.

The Public Services Board must also review and amend its local wellbeing plan and produce annual progress reports.

8 A Kenyan model

District, Provincial and National Environment Action Plans (NEAPs)

Section 38 of Kenyan Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) provides for the preparation of District, Provincial and National Environment Action plans every five years. The preparation of the District and Provincial Environment Action Plans commenced with initial training of six technical members from the District Provincial environment committees. This was through four regional training workshops based on the NEAP Manual. The District Environment Officers and Provincial Directors of Environment who are secretaries to their respective committees informed the District and Provincial Commissioners who chair the Environmental committees. Members of the District and provincial committees were informed and participated in preparation and validation of their respective environment action plans. Other committees including the District and Provincial Development and Executive committees were informed. During barazas or public meetings, members of the public were informed of the ongoing process. The District environment Action Plans are forwarded to the Provincial Directors of Environment to enable input of issues identified into the Provincial Environment Action Plans. The Provincial Environment Action Plans are passed to the National Environment Management Authority to incorporate issues identified at the Provincial level.

9 Managing giraffids: interactions between cultures and ecology

The giraffe has suddenly come to the fore as an endangered species in a rapidly deteriorating indigenous habitat.According to the Giraffe Conservation Foundation, at the beginning of this century there were about 140,000 giraffes roaming the plains and open forests of Africa. Today that number has plummeted by more than 40 percent. As with so many other species, the causes of this decline is rapid change which activates unmanaged conflicts between the human demand on its habitat for different ecosystem services.

Modern culture thrives on change. It creates new goods and services, and teaches us to want them. It adds new technologies, things and ideas at an increasingly rapid rate. Change in modern culture is propelled by all the same forces that cause change in traditional culture, only in modern culture the changes happen more quickly. Modern culture is a more mutable system that tends to change often. Another way in which traditional culture and modern culture differ is in their relationship to environment. Traditional cultures lived in close contact with their local environment. This taught that nature must be respected, cooperated with, in certain ritualized ways. One did not make huge changes in the environment, beyond clearing fields for agriculture and villages. Society saw itself as part of nature; its spiritual beliefs and values held humans as the kinsmen of plants and animals.

In contrast, modern culture creates its own environment, exports that cultural environment to colonies in far away places. It builds cities and massive structures. It teaches that nature is meant to be manipulated, to be the source of jobs and wealth for its human masters. It sees itself as being above nature. Its religions commonly cast humans as the pinnacle of nature: at best its paternalistic supervisors, at worst its righteous conquerors. This results in habitat loss, and habitat fragmentation, through food production, hunting and poaching, collecting wood for domestic fuel, using rivers and streams as waste sinks, artisan mining for minerals and the growth of urban settlements. The latter is linked with high population growth. For example, in 2015, Eye on Earth reported a study carried out in Uganda by the Population Reference Bureau. The message is that the country’s current population of 27.7 million will expand to 130 million by 2050, a nearly fivefold increase. Uganda’s current growth rate is 3.1 percent, while the world average is 1.2 percent. The PRB believes a low level of family planning is the main reason for the country’s extraordinary population growth. Only 20 percent of married Ugandan women between the ages of 15 and 49 have access to contraception. Women in Uganda have an average of 6.9 children, compared with a global average of 2.7 and an African average of 5.1.

Unfortunately, the decline in giraffes has occurred with little public attention. To place this in a larger conservation perspective there are an estimated 450,000 African elephants compared to 80,000 giraffe. Indeed, the giraffe is more endangered that the panda in terms of the numbers in its indigenous habitat.

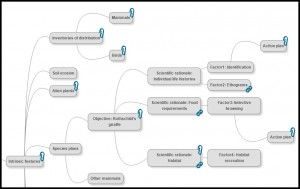

There are several large national nature reserves in Kenya with online public conservation plans which include the giraffe. There are also several privately owned conservancies, such as the Kigio Wildlife Conservancy, occupying 3,000 fenced off acres of a former colonial cattle ranch. These sites, protect smaller pockets of planned biodiversity that allow some species to utilize multiple cross boundary areas. Resilience-UK is using these operational plans as an information source to exemplify an online educational wiki, which compares the logic of different conservation systems being developed for controlling ecosystem services. In this context, there is scope in Kenya for developing a common conceptual format for conservation plans in order to share ideas, experience and achievements about managing habitats and species, between sites. Since wildlife and habitats transcend national boundaries there is also scope to promote ideas of transnational planning to a common conceptual format. The central philosophy is adaptive management (Fig 5) where monitoring of outcomes provides feedback to the objectives, hypotheses and management activities of the plan.

Fig 5 The logic of adaptive management

It was in the 1980s that the idea of developing a common conservation planning/recording system brought together UK government and non-governmental nature protection organisations to create a software database known as the CMS. This computer package was based on the needs of site managers to schedule and report on the outcomes of their day to day activities and share best operational practice.. The CMS is now developed and promoted by the Conservation Management System Consortium, a not-for-profit organisation. The system is the gold standard for conservation management in the UK and The Netherlands. As such, it provides a well-worked and tested planning, recording and reporting logic for making international comparisons, particular in the context of developing education/training packages to link communities and their local ecosystem services to support the topic of cultural ecology. A network of Wikis is the focus for this cross-curricular educational initiative.

Fig 6 Excerpt from a conceptual ecosystem services mind map https://atlas.mindmup.com/resilienceuk/kigio_wildlife_conservancy_a_concept_m/index.html

An ecosystem services mind map (Fig 6) is being developed to illustrate a conceptual management system based on the conservation plan produced by Projects Abroad in partnership with the Giraffe Research and Conservation Trust and the Kigio Wildlife Conservancy. As a concept management plan the mind map conceptualises a one-to-many database, which is the most appropriate software solution to make, record and report on operational management. The plan is taken down to the level of actions for one of its intrinsic features, the Rothschild’s giraffe, which is an iconic indicator of the the state of the ecosystem services of the African plains.

The family Giraffidae has two extant members: the savannah-dwelling giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) and the forest-living okapi (Okapia johnstoni). Native to Africa, this family is highly adapted for browsing, although the two species inhabit very different habitats, both feed at a level higher than any other sympatric terrestrial herbivore. The giraffe is the tallest living mammal, towering up to 5.9 meters above the ground. The forequarters of both species are overdeveloped, and the back slopes downward to the rump.

The fossil record of the Giraffidae begins in Africa during the Miocene, extending to the present on this continent. Giraffes also ranged widely in Eurasia from the middle Miocene to the Pleistocene. Some of these giraffes bore highly developed, branching horn-like projections. The modern-day okapi, on the other hand, closely resembles the ancestral form of the early Pliocene giraffids.

Competition for local ecosystem services also affects okapi conservation, which is very evident in the conflicts surrounding the declaration and management of the Congolese forest Okapi Wildlife Reserve, which is home to a substantial proportion of the remaining world population of okapi. One year after giving it World Heritage status the okapi was placed on the list of World Heritage in Danger in 1998, because armed conflict in early 1997, had led to the looting of facilities and of equipment donated by international conservation organisations, the incursions by thousands of miners seeking gold and rare metals and by bushmeat hunters and cultivators. Most of the staff were evacuated. By 2001, exploitation of the Reserve by armed militias, miners and hunters had decimated the animal population around all camps and the park was too dangerous to visit. That year UN agencies responded to pleas from staff and NGOs for international pressure to stop the destruction and help to restore funds, morale and order. The political situation is still fragile

10 Postscript

“This animal has a body as big as a horse but with an extremely long neck. Its forelegs are very much longer than the hind legs, and its hoofs are divided like those of cattle.

The length of the foreleg from the shoulder down to the hoof measured, in this present beast, 16 palms, and from the breast thence up to the top of the head measured likewise 16 palms: and when the beast raised its head it was a wonder to see the length of the neck, which was very thin and the head somewhat like that of a deer. The hind legs in comparison with the forelegs were short, so that anyone seeing the animal casually and for the first time would imagine it to be seated and not standing, and its haunches slope down like those of a buffalo.

The belly is white but the rest of the body is of yellow golden hue cross marked with broad white bands. The face, with the nose, resembles that of a deer, and in the upper part it projects somewhat acutely. The eyes are very large, being round, and the ears like those of a horse, while near its ears are seen two small round horns, the bases of which are covered with hair: these horns being like those of the deer when they first begin to grow. The animal reaches so high when it extends its neck that it can overtop any wall, even one with six or seven coping stones in the height, and when it wishes to eat it can stretch up to the branches of any high tree, and only of green leaves is its food. To one who never saw the jornufa before this beast is indeed a very wondrous sight to behold”

From Gonzalez de Clavijo’s account of his journey to Samarkand (1402-6). It reveals the considerable awe felt by a man who has just gazed at a giraffe for the first time.

This blog builds on the document ‘Ecological Restoration for Protected Areas’, produced by the IUCN. https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/PAG-018.pdf