Every generation writes its own description of the natural world, which generally reveals as much about human society as it does about nature. Donald Worster, 1977

1 Background

The ecosystem approach

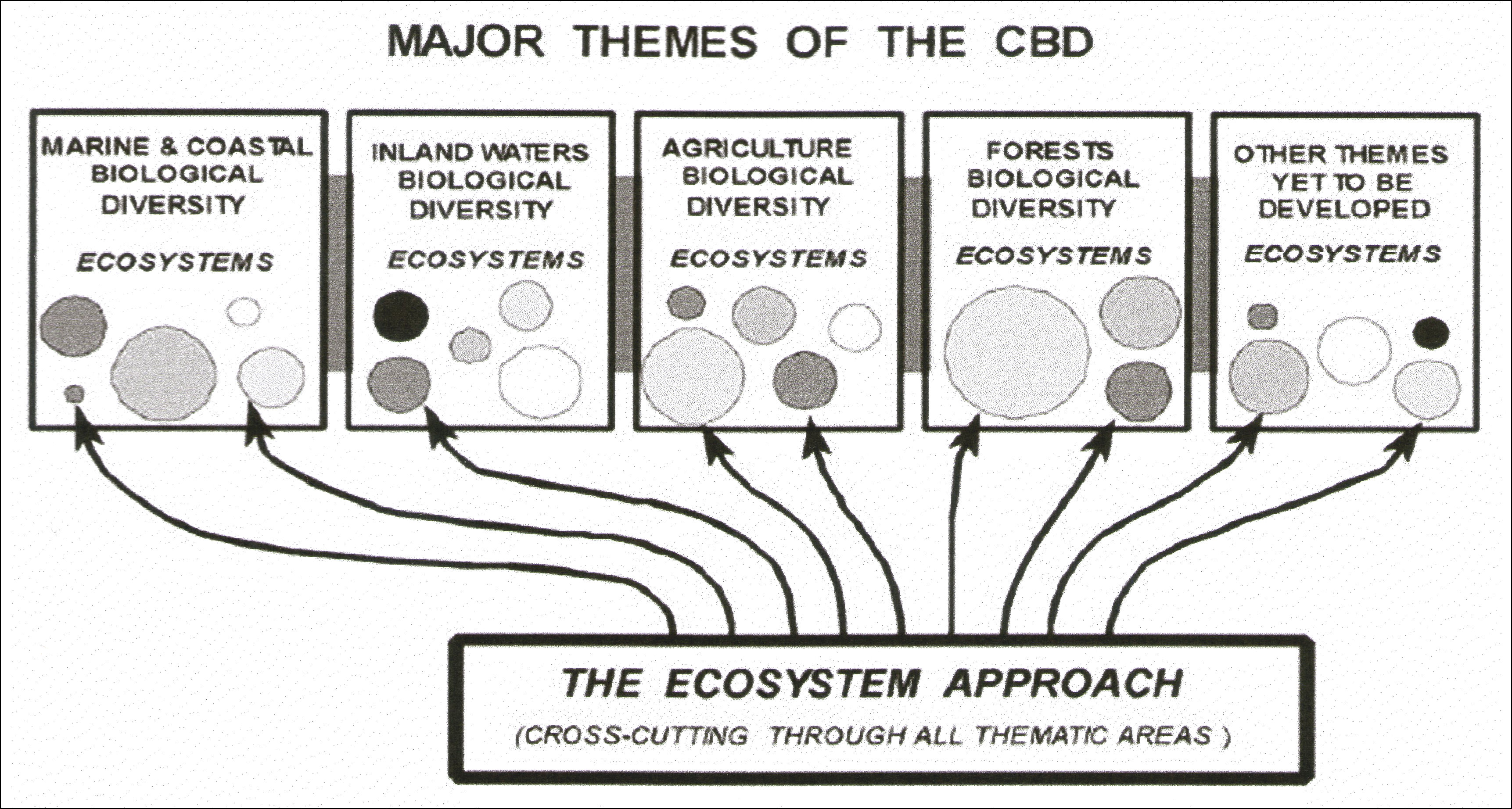

In 1998, the United Nations’ Environment Programme, through the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) at its meeting in Malawi, launched the ‘ecosystem approach’ to conservation management as an international policy. The Malawi conference defined the ecosystem approach diagrammatically (Fig 1) as a cross-cutting process of nature conservation through four thematic areas linking ecosystems at a landscape level with culture. These themes of cultural ecology were categorised as ‘marine and coastal’, ‘inland waters’, ‘agricultural’, and ‘forests’.

The four named themes in the original presentation of the ecosystem approach have now been augmented by the theme of ‘community biological diversity’. This theme encompasses the flows of resources into local communities that come from ecosystems and provide a range of social benefits. The services can be categorised by the following spatial characteristics:

* they are provided and used locally or at a wider landscape level;

* when they are provided locally they can be a form of global consumption, independent of proximity to the place of provision.

Fig 1 Major themes of the ecosystem approach (UNEP/CBD Malawi 1998)

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/cop/cop-04/information/cop-04-inf-09-en.pdf

The CBD recommended that the ecosystem approach should be taken because delegates decided that classical nature conservation had concentrated exclusively on rare uninhabited habitats, and failed to recognise that ecosystem functioning is vitally important for overall environmental quality in places where people live and work.

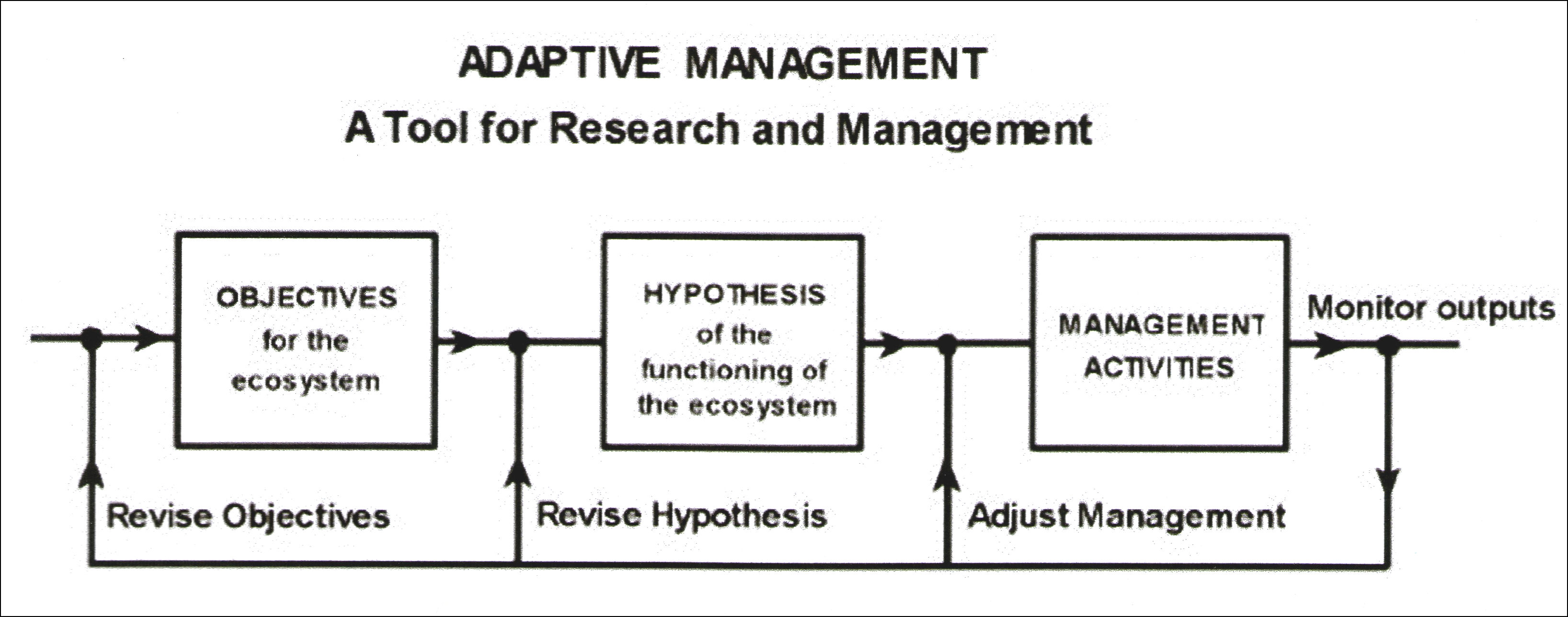

Because of the complexity of all themed areas identified at Malawi and their human interactions, the CBD stressed that managing the ecosystem approach needs to be adaptive, allowing for the modification of plans through ‘learning by doing’. The CBD presented this adaptive management system diagrammatically to show that monitoring the outcomes of the plans provided feedback for adjusting the underlying objectives and hypotheses of management (Fig 2).

Fig 2 Adaptive management a tool for research and management

http://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/cop/cop-04/information/cop-04-inf-09-en.pdf

Ecosystem services

Humanity has always depended on the services provided by the biosphere and its ecosystems. Further, the biosphere is itself the product of life on Earth. The composition of the atmosphere and soil, the cycling of elements through air and waterways, and many other ecological assets are all the result of living processes-and all are maintained and replenished by living ecosystems. Humanity is ultimately fully dependent on these flows of ecosystem services, while buffered against environmental change by culture and technology, This is why the ecosystem approach has now been adopted world wide as the central platform for the management systems of broad based nature conservation to deliver ecosystem services to sustain human well-being.

This ecological approach to the human economy can be traced to Herman Reinheimer’s book entitled ‘Evolution by Cooperation: a Study in Bioeconomics’. His thesis was that all organisms are ‘traders’ or ‘economic persons’ and must work to earn their way by rendering services to one another. A community of organisms that ceases to participate in the exchange of ecological services “cannot escape impoverishment”. In other words, the provision of services to humanity by ecosystems is actually part of a two-way obligation, which is expressed in the human economy through conservation management.

Reinheimer’s ideas about’ecosystem services’ were taken up in the late 1970s primarily as a communication tool to explain the dependence of human society on nature.

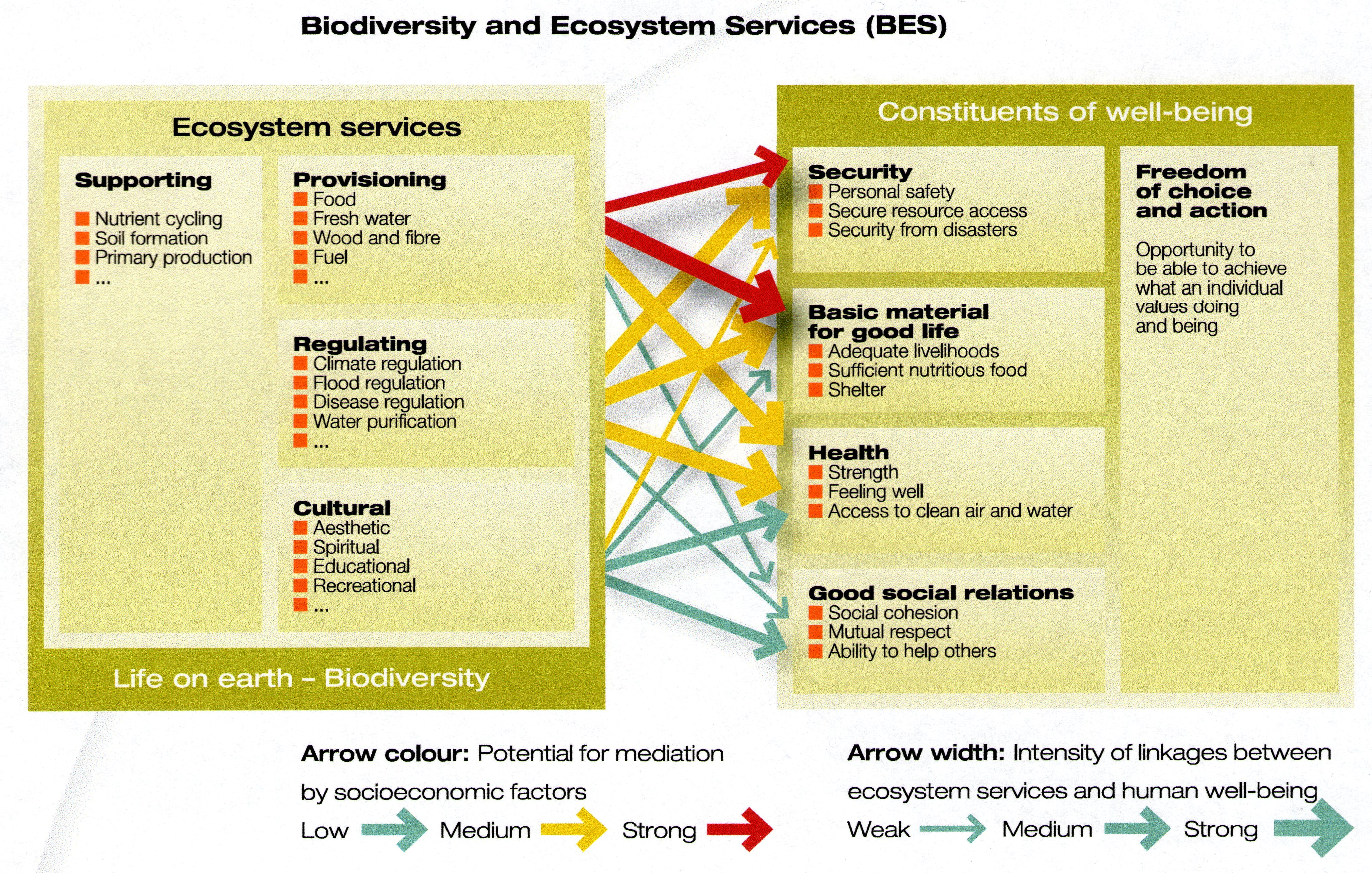

UNEP’s Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), published in 2005, marked a major milestone in the historical development of the ecosystem services concept. It sought a strong scientific understanding for how ecosystems affect human welfare and how they can be managed. Towards this end, the MA set out a typology of ecosystem services under four broad headings: ‘provisioning services’, ‘regulating services’, ‘cultural services’ and ‘supporting services’ (Fig 3). Ecosystem services now incorporates firm economic dimensions and provides help to decision makers for implementing effective conservation policies to support human well-being in the context of sustainable development.

Fig 3 Biodiversity and ecosystem services (UNEP March 2008)

http://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/bloom_or_bust_report.pdf

2 Role of local government

The theme of ‘community biological diversity’ is predominately concerned with ecosystem services that are managed at the local government/community interface. Here the objectives are to provide, security, health and good social relations in neighbourhoods, which, world wide, are increasingly urban (Fig 3). This leads to the hypothesis that cultural ecosystem services, as constituents of well-being, can be strongly correlated with the quality of life and particularly the well-being of those people who can become directly occupied with land use. However, up to now, the specific forms and relations between urban landscape elements such as parks, gardens, undesignated community green/blue spaces and quality of life have been elusive.

However, the exact terminology relating to ecosystems services is less important than the point that ecosystems provide valuable services for people. There is no single way of categorising ecosystem services, but they can be described in simple terms as providing:

* natural resources for basic survival, such as clean air and water;

* a contribution to good physical and mental health, for example, through access to green spaces, both urban and rural, and genetic resources for medicines;

* natural processes, such as climate regulation and crop pollination;

* support for a strong and healthy economy, through raw materials for industry and agriculture or through tourism and recreation;

* social, cultural and educational benefits, and well-being and inspiration from interaction with nature.

The MA community assessments were conducted across five continents in many different settings. The contexts ranged from remote, highly traditional people using ecosystems on a day to day basis, to recently democratized but poor semi-urban people who are forced to rely on ecosystems as safety nets during times of extreme poverty. At the other end of the spectrum were urbanized professionals who care about ecosystems and who want to manage them better for biological and cultural values. Apart from being in different countries and on different continents, the community assessments that formed part of the MA varied widely in terms of the livelihoods of the communities involved, the nature of the people’s relationship with their natural resources, the cultural characteristics of the community and the biomes or ecosystems where people were situated.

Urban ecosystems

Regarding the importance of urban ecosystem services, more than half the world’s population now lives in cities, compared with about 14% a century ago. The net flow of ecosystem services is invariably into, rather than out of urbanised places. These flows have increased even more rapidly than has urban population growth and the average distance of these flows, for example in supplying supermarket foods, has increased substantially as well.

Urbanisation radically modifies the ecology of landscapes where people live and work. The effects include alteration of habitat, such as loss and fragmentation of natural vegetation. Novel habitat types are created, such as roadside verges and avenues of trees. Resource flows are altered resulting in reduction in net primary production, increases in regional temperature and degradation of air and water quality. Many urban ecosystems experience more frequent disruption with the alteration of species composition, species diversity, and proportions of alien wildlife, particularly plants. Urban biodiversity, as measured by the number of different species living in cities, is often higher than that of rural regions. This is perhaps due to agricultural practices that favour turning large tracts of rural land over to monoculture of specific food plants and animal species. However, there is also a tendency for urban social inequity to be matched with inequity in the environmental quality of the urban landscape.

ICLEI, an international organisation that represents local governments for sustainability, mounted the first world congress on ‘Resilient Cities’ in 2010 and included biodiversity and related ecosystem services in their talks as a cornerstone for climate change adaptation. Members of ICLEI have made a commitment to sustainable development through the Local Government Biodiversity Roadmap and Local Action for Biodiversity (LAB).

The EU supports such further local authority commitment and awareness raising of the importance of ecosystem services. For example, by honouring the most sustainable cities with the European Green Capital Award, and establishing the legal framework to protect biodiversity through instruments such as the Natura 2000 network under the EU Habitats and Birds Directives, air quality directives, the Water Framework Directive and the development of a soil directive.

The EU is also developing a strategy on green infrastructure to protect biodiversity and ecosystem services in the 83 % of the EU territory falling outside the Natura 2000 network, including most parts of cities. The green infrastructure concept brings considerations for biodiversity and ecosystem services to the heart of wider spatial planning. It will be key to further strengthening sustainable urban development and related EU-wide spatial policies and actions like the urban dimension in regional policy, the EU Territorial Agenda and the Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities.

The key messages from the EU are:

* In Europe, where the overwhelming majority of people live in urban areas, tackling the interlinked challenges between biodiversity and its network of towns and cities is crucial to help halting biodiversity loss.

* Urbanisation can be an opportunity or a threat for biodiversity. Seizing the opportunity demands a mix of high quality urban green areas with dense and compact built up zones.

* Quality of life in cities depends on the existence of sufficient attractive urban green areas and corridors for people and wildlife to thrive. But equally important for urban life are the ecosystem services delivered by biodiversity in green areas outside city boundaries. This will entail the cultural shaping of ecosystem services to deliver cultural assets to communities and neighbourhoods.

* Although biodiversity and ecosystem services are global common goods, local and regional authorities have the legal power to designate conservation areas and to integrate biodiversity concerns into their urban and spatial planning. Public commitment is apparent in the numerous participatory Local Agenda 21 processes aimed at building sustainable communities that identify biodiversity as a precondition for resilient cities.

* Besides protecting areas, it is essential to integrate biodiversity into spatial planning at regional and local levels, including cities. Developing the European Green Infrastructure concept presents an opportunity to do this.

However, there is relatively little research on how urban ecosystems can be designed, built, maintained, and adapted to enhance ecosystem services such as water filtration, climate moderation, flood regulation, and a variety of cultural ecosystem services, including local heritage which is a record of past ecosystem services. Furthermore, cities cast large ecological shadows because they import products and services from distant places.

http://www.aibs.org/bioscience-press-releases/resources/Raudsepp-Hearne.pdf

3 Community ecosystem services plans

A community ecosystem services plan (CESP) is essential for managing the integrated delivery of ecosystem services to communities, neighbourhoods and families. CESPs are vital to the cost-effective integrated inputs of top down resources into communities. They are about the transfer of the ecosystem services approach into environmental management, although the type of conservation management system necessary to achieve this has not been sufficiently addressed so far.

Fundamentally, a CESP functions as a project database for channelling governmental/ private sector resources into joint local authority community actions and records progress towards outcomes that enhance and maintain local well-being. In this managerial sense, promoting the ideas of ecosystem services falls within the guidance to local authorities on implementing the UK’s Biodiversity Duty according to the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act of 2006. By promoting understanding and awareness of community ecosystem services, local authorities can meet their Biodiversity Duty by helping to encourage land managers, businesses, educational services and the general public, to act in ways that benefit biodiversity conservation.

Fig 4 Local authority guidance on the ‘Biodiversity Duty’ http://archive.defra.gov.uk/environment/biodiversity/documents/la-guid-english.pdf

The role of local authorities in providing external advice, education and awareness raising activities, can be split into four core areas (Fig 4). Raising awareness of ecosystem services and biodiversity run hand in hand as a cross-cutting theme that relates to all local authority functions, and is of significant importance in facilitating the implementation of the Biodiversity Duty. The core functions have close links and are also inter-related. For instance, many activities aimed at engaging the community are also likely to raise awareness of biodiversity, and may provide opportunities to link with local schools, environmental NGOs or public advisory services.

The key messages to local authorities regarding their Biodiversity Duty are:

Local authorities have an important role in promoting understanding and awareness of local ecosystem services, which underpins a wide range of biodiversity conservation activities.

Having regard for the conservation of biodiversity involves incorporating messages about the place of biodiversity messages into a wide variety of interactions with land managers, businesses, other organisations and the general public.

Methods include the operation of the education system, provision of advisory services, promotion of community engagement in ecosystem services, and raising awareness of their importance in everyday life through communications with the public.

4 Cultural shaping of ecosystem services for human well-being

Culture is the result of the two-way interaction between people and environment in search of ecological assets. The interaction is a source of creativity, imagination and innovation. It is a driving force for new and sustainable designs for life and a spur to economic development. In this respect, the current pattern of ecosystem services is the result of changes in the environmental knowledge, practices and beliefs that have occurred over the last 70,000 or so. Between 50 and 100,000 years ago the human population began to grow and spread, first in Africa and then across the world. With this expansion came a diversification of their languages, subsistence systems, patterns of social organization, and other cultural features. As more complex societies began to evolve about 5,000 years ago, subcultures- classes, castes, occupational groups, religious faiths -began to diversify within cultures. In the very long run, cultures actually created the environments to which its members must adapt genetically. This leads to the co-evolution of genes with culture because culture permits adaptation to a wide range of environments.

Adaptation results in the cultural reshaping of the Earth’s surface through the processes of gathering ecological assets. One can look at this cultural moulding of landscape from the standpoint of civilizations and nations all the way down to hamlets, neighbourhoods and individuals. Within this geographical spectrum of ecosystems and services it is possible to discern two levels of ecosystem management. On the one hand ecosystem services are provided that are clearly cultural assets at the neighbourhood and family level. On the other hand, there are natural assets of the wider landscape with which the local cultural assets merge and overlap. This distinction maps a typology of ecosystem services, which can be used to define the geographical elements of a conservation management system. This map is essential to trace outcomes through CESPs. In this connection, a CESP consists of scheduled actions, which are held in a database to enable a manager to track multiple projects to and from selected ecosystem services to people in the places where they live.

The smallest focal point for delivery of ecosystem services as cultural assets is the neighbourhood, which is increasingly conceptualised spatially as the square mile that people accept as being ‘their place’. It is sometimes easy to take for granted what one values in neighbourhood and the changes happening around it can seem hard to influence. To make it easier, the ‘Talking About Your Place’ toolkit was produced by Scottish Natural Heritage to help address these issues: it can help people gain a better understanding of their local place and develop ways of using this understanding to shape and enrich local plans and decisions about the provision of ecosystem services. It may also encourage celebrations of what’s special about place and stimulate schools to work with the people and places they serve to produce community ecosystem services maps. http://www.snh.gov.uk/docs/B1117673.pdf

In Wales, guidance for people to evaluate their square mile has been produced by the Design Commission for Wales under the following themes, which are fundamental to making a community well supplied with ecosystem services where people are content to live and work.

* context and character;

* movement;

* public realm;

* built form;

* materials and details.

http://rescuemissionplanetwales.wikispaces.com/My+square+mile

Both approaches take the view that cultural heritage is an ecosystem service because it can contribute to a sense of place by making people aware of past ecological interactions of those who came before and have left evidence of their way of life in the local landscape.

5 Making management maps

An example of a provisional typology for mapping community ecosystem services is set out in Figs 5-7. It addresses the need for citizens to become more innovative and resilient but also more engaged with the management of ecosystem services by becoming more resourceful and pro-social. As a set of pathways to action it is essentially a system to help build bridges between the kind of society we say we want to live in, and the kind of society we do live in. Only by overcoming this ‘social aspiration gap’ will communities be better placed to achieve more environmentally sustainable lifestyles facing them. To be cost effective and efficient means working with existing community organisations and through established communications channels based on current ways of thinking and doing things.

http://www.thersa.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/369490/The-Ecology-of-Innovation.pdf

Fig 5 Cultural reshaping of ecosystem services for human well-being

Taking as a starting point the local authority’s biodiversity duty, a potential communication channel would be through the existing structure set up to address this duty, which is expressed mainly in the production of the local biodiversity action plan and reporting on the state of local habitats and species to central government. To extend this current duty to the management of ecosystem services, a suitably trained area project manager within the biodiversity section of the local authority would be responsible for promoting and resourcing action plans for community projects and reporting on their outcomes. These projects would address the need to manage people’s interactions with ecosystem services in the community’s one square mile and the wider landscape (Figs 6 and 7).

The CESP management system could help bring together the principles of ecosystem services, which focus on life support systems, with more non-material services such as cultural assets and tourism. Enhancing the local production of ecosystem services that support human well-being can enhance the quality of life in cities while reducing the environmental demand on distant ecosystems. However, to achieve such a goal requires the integration of ecosystem service concepts within engineering, architecture, and urban planning.

Fig 6 Environmental services as cultural assets for communities neighbourhoods and families

There is no standard way of making connections between citizens and the management of the ecosystem services upon which they depend for well-being. However, there can be no doubt that when community-led projects are well connected, both into their communities and into higher level policies and resources of government, the project team is more efficient. It has more detailed and locally specific knowledge about needs and how they can be met and also about local assets and resources. Local knowledge can identify and fill very specific gaps in provision that might be missed or be unappealing to larger scale providers. Local community organisations guided to operate their own CESPs can be better at generating new ideas from different sources by accessing people that are not usually reached. They are able to motivate those around them by building on existing networks and established, trusting relationships to meet their own planning goals.

Fig 7 Environmental services as natural assets in the wider environment