1 The spill

The Sea Empress oil spill occurred at the entrance to the Milford Haven Waterway in Pembrokeshire, Wales, on 15 February 1996. Sailing against the outgoing tide and in calm conditions, at 20:07 GMT the tanker was pushed off course by the current and became grounded after hitting rocks in the middle of the channel. The collision punctured her starboard hull causing oil to pour out into the sea. The Sea Empress, a state of the art supertanker, was en route to the Texaco oil refinery on the shores of the Haven near Pembroke.

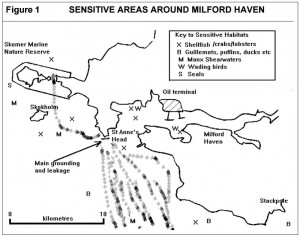

Tugs from Milford Haven Port Authority were sent to the scene and attempted to pull the vessel free and re-float her. During the initial rescue attempts, she detached several times from the tugs and grounded repeatedly – each time slicing open new sections of her hull and releasing more oil (Fig 1).

A full scale emergency plan was activated by the authorities.

Fig 1 The site and scale of the problem

During the next few days, frantic efforts were made to pull the vessel from the rocks.. Tugboats were drafted in from the ports of Dublin, Liverpool and Plymouth to assist with the salvage operation. Over the course of a week, she spilt 72,000 tons of crude oil into the sea. The spill occurred within the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park – one of Europe’s most important and sensitive wildlife and marine conservation areas. It was Britain’s third largest oil spillage and the twelfth largest in the world at the time (Fg 2).

Fig 2 Sensitive areas around Milford Haven

2 The place

The Sea Empress disaster occurred in Britain’s only coastal national park and in one of only three UK marine nature reserves. The tanker ran aground very close to the islands of Skomer and Skokholm – both national nature reserves, Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Protection Areas and home to Manx shearwaters, Atlantic puffins, guillemots, razorbills, great cormorants, kittiwakes, European storm-petrels, common shags and Eurasian oystercatchers. The whole area is one of National Park and Heritage Coast, with over 30 SSSIs, 2 of the UK’s 3 marine nature reserves (Skomer, Lundy), and sites of European conservation importance.

Birds at sea were hit hard during the early weeks of the spill, resulting in thousands of deaths. The Pembrokeshire grey seal population didn’t appear to be affected too much and impacts to subtidal wildlife were limited. However, much damage was caused to shorelines affected by bulk oil. Shore seaweeds and invertebrates were killed in large quantities. Mass strandings of cockles and other shellfish occurred on sandy beaches. Rock pool fish were also affected. However, a range of tougher shore species were seen to survive exposure to bulk oil and lingering residues.

Bird counts by the RSPB, CCW and other groups had revealed 12-13,000 birds in the Haven estuary on 13 February. Outside the Haven, guillemots were returning 2-3 weeks early to their colonies of which Skomer, Stack Rocks and Ramsey Island are the largest. There were also over 60,000 gannets and 10,000 seaducks (scoters) in the adjoining bays and sea areas. Manx shearwaters had yet to return and are were generally beyond the range of the oil. Birds in the area were very vulnerable to the many patches oil and by Feb 27, over 1,200 oiled birds were in treatment and some 400 bodies had been picked up (some experts consider these are likely to have represented only 10% of the total number so affected). In addition, some 5,000 of the birds that were flying were seen to have been oiled to some degree. A rescue centre for oiled birds was set up in Milford Haven. But, according to the Countryside Council for Wales (CCW), the government’s conservation organisation in Wales at the time, over 70% of cleaned, released guillemots died within 14 days. Just 3% survived two months and only 1% survived a year.

The Pembrokeshire coast is home to common porpoises and bottlenose dolphins. Significant numbers of both species were recorded in the waters off the Skomer Marine Nature Reserve during the spring and summer of 1996. But he effects of the oil and chemical pollution on these species remains unknown.

3 The effects

Oil spread some 10km up the estuary. Mortality of intertidal fauna was 100% near the main spill and oil also spread over wide areas of coast to the north and south of the Haven entrance; additional contamination is likely to have taken place with onshore winds. Potentially sensitive estuaries were boomed by the river authority , but the foreshore could not be so protected.The main commercial resources at risk outside the Haven were coastal crab and lobster fisheries and offshore fin fisheries – both from the reality and perception of contamination. Most vulnerable were the Haven’s shellfisheries (mainly mussels). Fishermen applied a voluntary ban on sales from the area and there was an immediate ban on fishing off the coast of Pembrokeshire and south Carmarthenshire, which had a devastating impact on the local fishing industry. The ban remained in place for several months and was lifted in stages. Many local fishermen received financial compensation for the loss of income due to the ban.

The major problem encountered initially with the Sea Empress was the failure to offload the oil from the vessel until it had been badly damaged and lost over half its cargo. Offloading to tankers was thwarted by the heavy weather and the inability of the tugs available to prevent the Sea Empress from repeated grounding. The tanker was removed from the rocks and berthed to allow off-loading the remaining oil on February 21/22, but not before 70,000 tonnes had been spilt. The oil was Forties (North Sea) crude, which is comparatively light and therefore contains a substantial proportion of volatile components. This is amenable to dispersant spraying provided it can be attacked within several hours, after which ‘mousse’ (water in oil emulsion) can be formed, rendering it less amenable to dispersion.

In view of the richness of the local marine life the Ministry of Agriculture Fisheries and Food, (MAFF) withheld approval for the use of dispersants within Milford Haven, in a coastal strip one nautical mile from the shore and within one nautical mile of Skomer Island National Nature Reserve. Six aircraft were able to spray the bulk of the slick as it moved into the outer Bristol Channel, and reported success (combined with the generally active sea conditions) in dispersing much of the oil in open water. After the vessel was moved inside the Haven on 23 Feb, spraying was discontinued because there was no oil outside the Haven amenable to dispersion. By this time, some 440 tonnes of detergent had been sprayed – perhaps dispersing 4-8,000 tonnes of oil.

With evaporation removing perhaps 30-40% of the oil, many thousand tonnes of weathered oil and mousse remained to contaminate seabirds and the sandy and rocky shores. Remnants in the form of sheens and weathered oil/mousse were widespread, affecting waters and shores from North Devon to north of Skomer, and as far as Porthcawl into the Bristol Channel.

4 The outcomes

The main containment and dispersement of the oil slick at sea was completed within six weeks. However, the removal of oil on shore took over a year until the late spring of 1997. Three years after the spill, small amounts of oil were still found beneath the sand on sheltered beaches and in rock pools.

Bad as they were, the effects of the spill on local wildlife were not as serious as initially predicted. This was due in part to the time of year when the spill occurred. In February, many migratory birds had not yet arrived back in Pembrokeshire for breeding. Along with stormy weather, which helped break-up and naturally disperse the oil, the effect on wildlife would have been much worse if the spill had occurred just a month later when the prodigious colonies of sea birds would have been nesting. The spill would undoubtedly have been catastrophic for both the environment and local economy if it had occurred during the summer months.

The spill occurred just a few weeks before the Easter break when many holidaymakers would be visiting the area. Some sheltered beaches and tidal estuaries were still covered with oil (Fig 3), but the main tourist locations of Tenby, Saundersfoot, Pendine, Manorbier and Bosherston were superficially cleaned .

A large clean-up operation began as soon as the Sea Empress started spilling oil. Volunteers and paid hands alike, came together to restore the beautiful beaches of Pembrokeshire. In the immediate days and weeks that followed, one thousand people, including local celebrities, worked around the clock to rescue oiled birds and remove oil from beaches using suction tankers, pressure washers and oil-absorbing scrubbers. The main clean-up operation lasted several weeks and continued on a reduced scale for over a year.

Fig 3 Clean up at Tenby

Almost three years after the spill in January 1999, Milford Haven Port Authority was fined a record £4m after pleading guilty to the offence of causing pollution under the Water Resources Act 1991. The MHPA was also required to pay a further £825,000 prosecution costs by agreement.

The cost of the clean-up operation was estimated to be £60m. When the effects to the economy and environment are taken into account, the final cost is estimated to have been twice that, at £120m.

By 2001, it was officially accepted that the affected marine wildlife population levels had more-or-less returned to normal.

5 Resilience

The rapid recovery of the ecosystems affected by the oil spill illustrate ecological resilience, also called ecological robustness, the ability of an ecosystem to maintain its normal patterns of nutrient cycling and biomass production after being subjected to damage caused by an ecological disturbance. The term resilience is a term that is sometimes used interchangeably withrobustness to describe the ability of a system to continue functioning amid and recover from a disturbance.

The resilience or robustness of ecological systems has been an important concept in ecology and natural history since Charles Darwin, who described the interdependencies between species as an “entangled bank” in On the Origin of Species (1859). Since then, the concept has come to hold special importance in the areas of environmental conservation and management. Its significance to the well-being of humans and human societies has also been recognized. The loss of an ecosystem’s ability to recover from a disturbance—whether due to natural events or due to human influences such as overfishing and oil pollution—endangers the benefits from ecosystem services (e.g., food, clean water, and aesthetics) that humans derive from that ecosystem.

Despite the scientific evidence that is available to the contrary, there is frequently a basic presumption that long-term damage must have been caused by an oil spill. Predictions of an environmental disaster therefore frequently accompany the first reports of a spill, long before any assessment of the true impacts and their likely duration has been made. It is in this sense that oil spills as ecological experiments’ do not generate principles of ecological resilience, because of possible underlying ecological processes from an unknown pre-spill baseline.

6 The responsibility

The official 1997 report into the Sea Empress oil tanker spillage in Wales blames the pilot for the initial error – but also catalogues a whole series of subsequent mistakes. In a separate move, the Milford Haven port authorities were prosecuted for their handling of the incident.

The report, by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch, says that the pilot, failed to keep the 147,000-tonne Liberian-registered tanker in the deepest part of the navigation channel. This was partly due to inadequate training and his lack of experience with such large vessels. One of the MAIB’s recommendations is improved training and examination of pilots.

The pilot was found guilty of incompetence by the Milford Haven Port Authority and was demoted. But he successfully appealed and was able to resume working with large tankers.

After the tanker had run aground, however, the report says there were not enough tugs of the right power and manoeuvrability available to refloat her. In addition, the authorities did not understand the effect of local tidal currents, the MAIB concludes. This led to the vessel being swept aground for a second time.

It was this second grounding which caused most pollution. The initial accident spilled some 2,500 tonnes of oil compared to nearly 70,000 tonnes in the second incident.

The MAIB also criticises Milford Haven Port Authority’s disaster planning. The accident was outside the scope of its emergency plans and the crisis management team became too unwieldy for effective action in a rapidly-changing environment.

National authorities also come in for criticism from the MAIB. The Marine Pollution Control Unit’s national contingency plan is described as “deficient”. It did not deal clearly with the unit’s involvement in the salvage of a vessel within harbour waters and it did not cater sufficiently for an incident which quickly worsened.

7 The culture shock

Natalie Beyer, who was living in Germany at the time, but who had relatives in the local community, wrote a dissertation on the disaster. She described the reaction of the people living in and around Pembrokeshire to the disaster was one of anger and sadness first of all which was followed by a ground swell of public opinion to prevent it happening again.

‘They saw all the beaches they loved to visit covered with thick black oil and they could smell the stinking fumes. The newspapers were full of letters from the public, in which people expressed their bitterness and frustration about the situation and called it “shameful” and “a complete tragedy”. Even young children were obviously very upset and touched, as they were forced to realise that their former “playground” beaches, with all their rock-pools, containing interesting creatures like sea anemones and water fleas and the occasional crab or star fish, with their huge variety of shells they loved to collect, the rocks and cliffs they enjoyed climbing on, the safe clear water for bathing in and with all the adventures these beaches had to offer, had turned into horrible, oily, ugly places covered with dead fish and birds and other sea creatures. During my visit in Wales I talked to many parents who told me they had been too worried to let their children go to the beaches, as they had been afraid that they might be harmed in their health by the oil lying everywhere, not to mention the problem of removing the oil stains from their clothing. The children wrote down their feelings or expressed them in paintings, composed poems, wrote little stories and also sent letters to the Prime Minister to tell him their disgust and sadness at what had happened. Everyone was upset and angry that the disaster had occurred in the first place and that, when it had taken place, the salvage operation had been so slow and full of mishaps. Most local people I talked to were demanding an independent public inquiry, so that those responsible for the catastrophe would also be made responsible for it with all consequences. Action groups were formed and these involved themselves in the clean-up processes. Local collections to support these groups raised high sums of money. One housewife in Freshwater West, a magnificent beach, which was particularly badly polluted, started collecting signatures against the use of single-skin tankers, in order to reduce the risk of another similar disaster.’

Natalie Beyer’s account in full

8 What happened next

Following the spill, the Sea Empress was repaired and renamed five times. In 2004, she was sold and moved to Chittagong as a floating production, storage and offloading unit. In September 2009, she was acquired by Singapore-based Oriental Ocean Shipping Holding PTE Ltd, renamed MV Welwind and converted from an oil tanker to bulk carrier. In 2012, she was renamed for a fifth time and is currently known as Wind 3. She remains prohibited from entering Milford Haven.

Since the Milford Haven disaster, globally, there have been about 100 more oil spills up to 2015.

The disaster happened when the schools of Pembrokeshire had opted to take part in the Schools and Communities Agenda 21 network, the Welsh educational initiative outlined in the previous blog. The young people were very upset and these emotions sparked a burst of creativity to express their feelings in poems and pictures. This is exemplified by the following poem by Bethan Swaine. The National Museum in Cardiff hosted SCAN fora for children, affected and unaffected to discuss the issues of dependence on an oil economy in a pristine nature conservation area.

A Fisherman’s Life

A lonesome figure at the clifftops being battered by the sea.

Hands in his pockets, shoulders shrugged, head bowed, weeping unashamedly.

Thinking of how for all his life, he’d fished around the Pembrokshire coast,

And how with pride when asked what he did “I’m a fisherman” he’d boast.

What now for his future? What would become of the team?

What would be moored in the harbour, where his fishing boat had been?

No other life had he ever known – the sea set him free.

No seabirds flying, no seals playing, no dolphins for company.

Then he turned his head and looked at the crowd.

And realised they too were sharing the sound.

Instead of the sea crashing full of life onto the shore,

It crept in carrying its burden of oil, each wave bringing more.

The air reeked of oil, of death, of human sorrow.

We all knew that today was the same recipe for tomorrow.

The desperate fight to clean oil off the beach.

Crying with frustration for the wildlife just out of our reach.

This thick black stuff – the produce of modern man’s needs.

This stuff called oil, at what cost for man’s greed?

To take another man’s living, to spoil our beautiful coast,

And leave its memory behind like a sorrowful ghost.

Bethan Swaine Yr.9

Ysgol Gyfun Dewi Sant

9 Newspapers and reports

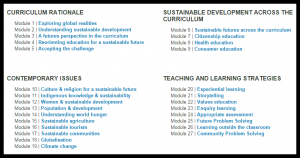

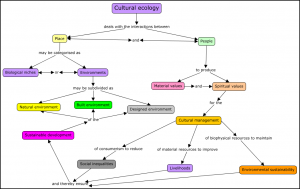

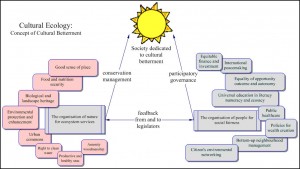

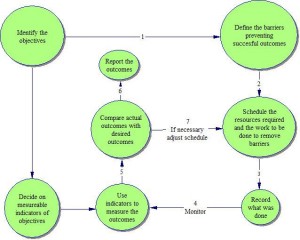

A database of newspaper cuttings was produced as a memorial resource for the Schools in Communities Agenda 21 Network (SCAN), which had the aim of encouraging pupils to engage in the problems, issues and challenges of cultural ecology associated with local economic development. It was part of the response of children trying to understand, and come to terms, with the oil spill which had assaulted their coastal paradise (Fig 4).

Their cuttings can be accessed as a Google document from HERE

Fig 4 Oiled seal on Skomer Island NNR: pictured by Warden Mike Alexander