An initial approach to this subject may be found in: Bellamy, Denis. (1980). ‘A biological approach to the teaching of dance aimed at broadening the area of dance education within movement studies’. Physical Education Review. Volume 3 Number 1 pp-34-40.

“It is not long since three words were repeated as a magical spell that was to change our lives drastically – ‘scientific-technical progress’. The whole idea and final goal of the progress became an end in itself and the progressive social movement for the realisation of the principle ‘Everything to the benefit of man!’ receded into the background. The intensification of the self-destructive processes was accompanied by local ecological shocks such as the pollution of the water of Lake Baikal, Caspian and Ladoga, soil amelioration at Polesye, construction of the St. Petersburg dam, etc., the logical succession of which was the global disaster of Chernobyl. Cataclysms in the nature and economy shifted humanitarian values to the background. Time will show whether it will be uncontrollable nuclear energy or a spiritual Chernobyl paralysing the aesthetic and historical processes of culture that will prove to be a more destructive force in laying waste civilisations. No doubt the triad, ecology of mankind – ecology of culture – ecology of environment, is very topical”.

Ivan Kruk. http://www.folklore.ee/rl/pubte/ee/usund/fbt/kruk.pdf

1 Learning ecologies

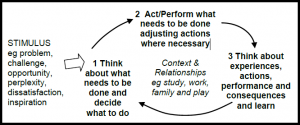

UNESCO defines Kruk’s three social ecologies, of ‘mankind’, ‘culture’ and ‘environment’, within its long standing programme linking humanity and the biosphere. They comprise, all forms of traditional and popular folklore where they are the social systems of intangible heritage. They are communicated through oral traditions, customs, languages, music, dance, rituals, festivities, traditional medicine and pharmacopoeia, the culinary arts and all kinds of special skills connected with the material aspects of culture, such as tools and the workplace habitat. Also included are peoples’ learned processes along with the knowledge, skills and creativity that inform and are developed by them, the products they create and the resources, spaces and other aspects of social and natural context necessary to their sustainability. These are all processes of survival which provide living communities with a sense of continuity with previous generations and are important to cultural identity, as well as to the safeguarding of the cultural diversity and creativity of humankind. In other words they are learning ecologies (Fig 1).

Fig 1 Model of a learning ecology

Barbara Kirchenblatt-Gimblett classifies these processes as metacultural heritage. She points out that unlike other living entities, whether animals or plants, people are not only objects of cultural preservation but also the subjects. They are not only cultural carriers and transmitters, but also agents in the heritage enterprise itself. They speak of collective creation within a particular local learning ecology.

As learning ecologies they carry the whole package of collective educative humanitarian works originating in a given community in a given time period and are based on tradition. Their creations are transmitted orally or by the gestures of dance and are modified over time through a process of collective recreation. It is intangible heritage that is dynamic. The task of educators is not only to define it for its preservation, but also to act as culture-makers, creating survival stories needed to embed all peoples safely in an expanding, unstable, global human ecological niche. In Kruk’s words this kind of story-telling signifies: “a progressive social movement for the realisation of the principle, Everything to the benefit of man!”

2 Behavioural coalitions

The term ‘ecology’, in our daily lives, places us in the perspective of human evolution and relates to how we have evolved humanitarianism to take care of ourselves, to conserve and relate to what we value in our landscape and each other, and ponder on whether or not we feel ‘at home’ in relation to the daily physical and social pressures that surround us. Education through gesture defines dance in this anthropological dimension. Dance as a learning ecology is a discipline for studying the purposefully selected sequences of human movement which have aesthetic and symbolic value, and are acknowledged as dance by performers and observers within a particular culture. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire of movements, or by its historical period or place of origin. In these ecological terms dance is a behaviour by which people have an evolutionary predisposition to form coalitions; to make a pact or treaty among individuals or groups, during which they cooperate in joint action, each in their own self-interest, joining forces together for a common cause. R.D. Alexander believes that the ability to form coalitions arose because the real challenge in the human environment throughout history that affected evolution of the intellect was not climate, weather, food shortages, or parasites—not even predators. Rather, it was the necessity of dealing continually with our fellow humans in social circumstances that became ever more complex and unpredictable as the human line evolved. Social cleverness, especially through success in competition achieved by cooperation, becomes paramount. Nothing would select more potential for increased social intelligence than a within-species co-evolutionary ‘arms race’ in which success depended on effectiveness in social competition.

Dance is a powerful evolved coalition-maker because it connects people to belief systems that determine our ecological niche. It is a folkloric route to discover and transmit the underlying cultural values of Kruk’s three ecologies, their uncertainties, fears, ambitions, motivations and morals. Examining these archetypes of the human subconscious is important when thinking about ecological and cultural conservation: They represent the successful societal collective and inherited patterns of thought. As one of the most powerful communication systems dance should be at the heart of a global education system to present the multiple belief systems, across cultures, which are occurring simultaneously in any given place at any given time. These systems encompass modern folklore, which was succinctly defined by William A. Wilson. He wrote, in his paper, ‘The Deeper Necessity: Folklore and the Humanities’ (in the 1988 Journal of American Folklore), as follows:.

“Surely no other discipline is more concerned with linking us to the cultural heritage from the past than is folklore; no other discipline is more concerned with revealing the interrelationships of different cultural expressions than is folklore; and no other discipline is so concerned …with discovering what it is to be human. It is this attempt to discover the basis of our common humanity, the imperatives of our human existence, that puts folklore study at the very center of humanistic study”.

While the world’s major religions are highly influential in building behavioural coalitions and include archetypes of ‘humankind’, ‘culture’ and ‘environment’, looking only at the way these ecologies are represented in organized religion leaves out a much wider breadth of collective knowledge about human survival. This is where, the examination of modern folklore, defined by stories, poetry, music and dance is valuable because of their deep spiritual, political and historical reaches. Folklore today is an important knowledge collective which speaks to common global spiritual concepts, transcending religious divisions and values. It encompasses ideas on contemporary history and localized environments, something that religious texts alone do not; folklore should be brought to the fore as a category of knowledge that best embodies the collective unconscious of all kinds of cultures at different stages of development..

There are many subdivisions of folklore, but it is dance that, since time immemorial, societies have used for their spiritual, physical, socio-political and economic advancement. For this reason, dance means different things to different societies with underlying different preoccupations. While to some it is a channel of expression of feelings of joy, hope, aspiration, anger, hatred, sadness, happiness, etc, others see it as the transformation of ordinary functional and expressive movement into extraordinary movement for extraordinary purposes. These varied meanings explain why the physical and psychological effects of dance enable it to serve many functions. In this context, it is commonly accepted that dance is a treasure-trove of social values. For instance, it is against a background of multiple values claimed for ‘community dance’, that Gordon Curl highlights the relevance of its aesthetic values and their noticeable absence in current community dance dialogue. Yet, the gap between dance and understanding its community applications has been known for almost a century. This is what Rudolf Laban said in his address to a 1936 Pre-Olympic Games gathering in Germany,

‘… Interest in the idea of modern community dancing seems to be widespread, for today I am able to look on your assembly of nearly a thousand people who have come here as representatives from our movement-choirs in more than sixty cities…’

His use of the term ‘movement-choirs’ is significant because singing, like dance, is a profound coalition maker. From Laban’s remark by we might well question the nature of the ‘interest’ of those ‘thousand people’ engaged in community dance!. Was it social, health, sport, therapy, aesthetic, artistic, political – or a combination of these?

Rudolf Laban created a system of analysing movement characteristics, as pathways through space, and the ‘effort’, ‘shape’ and ‘drive’ of a human movement. Known today as Laban Movement Analysis, Laban also developed a system of movement notation, known as Kinetography for documenting professional dance practice. His work, based in England after the second World War, established dance as a special form of social communication and inspired educational dance as a cross curricular subject, incorporating, acting, therapy, and workplace assessment. An important message from Laban’s work is that if, through dance, we change our ways of seeing and believing, then our ways of doing will follow suit. However, ‘movement analysis has failed to penetrate and diffuse naturally into the general education system at any level.

3 Coalition dancing in Tonga

Any dance gathering can be taken as an example of the multipurpose communicative value of dance. For example, dancing in Tonga can be used as a demonstration that it is imperative that we must go back to the more basic art of poetry to understand dance. This is because understanding poetry is essential if one is to understand the meaning of dance. On the other hand, if one is to study poetry or any other verbal art, it is essential to study dance, for today’s folklore, as ever, is expressed mainly through the medium of dance. Folklore and dance, then, are interrelated expressive human behaviours saying something uniquely important about the relationships between culture and environment.

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is a Polynesian sovereign state and an archipelago comprising 177 islands. There are two basic kinds of dance in Tonga—one which has movement as its main element, and one which accompanies poetry. The latter type can further be divided into two types. One type sings the praise of the royal family, the high chiefs, and an ethnocentric love of Tonga. It is essentially an expression of allegiance of the many islanders to a central established political and social order. The second kind comprises legends and folklore from Tonga’s hallowed past, and also from more recent times. Indirectly, however, this second type of poetry functions in the same way as the first. They can be unified in terms of their function of signalling that Tongans belong together; they are a cultural coalition.

Fig 2 Tongan lakalaka

The usual kind of Tongan dance that accompanies poetry is called lakalaka, which literally means “to walk” and, indeed, the leg movements are basically a walk that moves one step to the left, then one step to the right, and occasionally forward and back. The arm movements (Fig 2) are graceful and intricate, deriving their distinctive character from the rotation of the lower arm. The dance is performed by all the men and women of a village ranged in two or more rows facing the audience. The men stand on the right side (from the observer’s point of view) and women stand on the left; the order in which they stand is determined by social status. The men do one set of virile movements while the women do another set of very graceful movements so that there are two dances going on simultaneously. Each group interprets the poem in a manner consistent with the Tongan view of movements suitable and appropriate for each sex. The movements dramatize the poetry. They do not pantomime the words, nor do they symbolize in the sense that one movement symbolizes one phrase, or idea. Rather they are figurative: the movements create an abstract picture to which a number of meanings can be assigned, and conversely, one idea can be alluded to by several different sets of movements. As with modern contemporary dance the meaning is in the mind of the beholder

4 Community dance

One of the problems facing any commentator on ‘community dance’ is the sheer breadth and scope of the concept itself – a breadth and scope illustrated in the Report submitted by the Foundation for Community Dance to the UK Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2004), which affirms that:

‘Community Dance practice and provision recognises an astonishingly broad diversity of dance styles and traditions: we identify 42 different forms in our Mapping research, including Ballet and contemporary dance, folk dance, African People’s Dance, South Asian classical dance, popular social dance, as well as a range of ‘national’ dances – 4.78 million people participated in community dance activity…’

Ken Bartlett, in his article in the Laban Guild Magazine, questions the concept of ‘community dance’ by asking: ‘Is every kind of dancing community dance?’ To which he replies: ‘a qualified yes’! If this is the case, community dance (with some qualifications) must hold hegemony over the whole domain of dance – it spreads its tentacles over a vast territory of terpsichorean space – an all-embracing ‘community of dance’!

Ken Bartlett and his colleagues have examined community dance over the years and have discovered a treasure-trove of putative ‘values’. There are claims of: ’emotional and mental health’, ‘mood enhancement’, ‘stress reduction’, ‘anger management’, ‘energising and revitalising experience’. At a more general level there are designated values of: ‘celebration the human body’, ‘equality of opportunity’, ’empowerment and human rights’ – as well as ‘the amelioration of social exclusion’, the ‘reinvigorating pride in where people live’, ‘relieving suffering or violence’ and ‘making the world a better place’.

This remarkable list of accreditations for community dance would seem to provide a panacea for all educational ills! But Bartlett cautiously believes that we should do a little ‘prodding and poking’ at these widespread claims, by asking: ‘Why are people so keen to involve members in community dance? Surely’, he says, ‘they can be empowered in other ways and could be members of all kinds of groups concerned with wholeness of their being’. Perhaps, some carefully controlled research would determine whether or not such groups, including community dance, were consistently – rather than anecdotally – capable of achieving such claims. Could it be that in attempting to focus on ‘stress reduction’, ‘anger management’ or the ‘alleviation of ‘social exclusion’ etc., that community dance would itself become emasculated – transformed into such specialised domains as ‘psychotherapy’, ’emotional rehabilitation’ or ‘social engineering’ – thus diverting attention away from community dance as an end in itself and thereby losing its integrity as an autonomous aesthetic/artistic pursuit? Such a perspective points to the need for research into ways in which community dance can become the hub of lifelong learning for individuals and communities.

As an example of what community dance can achieve, In the spring of 2004, Jennifer Monson led a team of experimental dancers from Texas to Minnesota, following the northern migration pathway of ducks and geese. This was known as BIRD BRAIN, one of several ‘Navigational Dance tours’ that Monson has organized. The dancers stopped in ten communities along the Mississippi migratory flyway. Each stop was comprised of a public outdoor performance, a panel focusing on local migration issues, and a dance workshop linking migration with how the body navigates. The tour lasted eight weeks, beginning as the first waterfowl began to migrate and ending as the last birds arrived at the northern tip of the country. For this tour, Monson developed a classroom resource guide as a legacy to engage elementary schools in each community along the way

5 Evolution of dance

Behaviour is what all living things do. It can be defined more precisely as an internally directed environmental system of adaptive activities that facilitate survival and reproduction. Ethology is the scientific study of animal behaviour — particularly when that behaviour occurs in the context of an animal’s natural environment. Ethologists observe, record, and analyse each species’ behavioural repertoire in order to understand the roles of development, environment, physiology, and evolution in shaping that behaviour for individual and group survival. Dance is an example of human ethology.

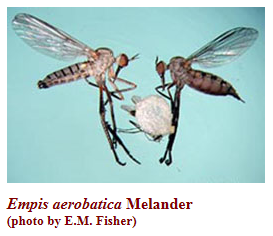

Both information and social cohesion determine collective decisions in animal groups. Before there were people, swarm behaviour, or swarming, had evolved as a collective behaviour exhibited by animals which aggregate together, perhaps milling about the same spot or maybe moving en masse or migrating in some direction. As a term, swarming is applied particularly to insects, but can also be applied to any other animal that exhibits a gathering-together behaviour. The term flocking is usually used to refer specifically to swarm behaviour in birds, herding to refer to swarm behaviour in quadrupeds, shoaling or schooling to refer to swarm behaviour in fish. The following paragraph summarises the swarming behaviour in a group of insects, the family “Empididae”, known as ‘dance flies’.

Fig 3 Exchange of a nuptial gift between a pair of dance flies

The “Empididae” is a diverse group of flies consisting of over 4,000 described species worldwide and about 800 described species in America north of Mexico. Numerous species remain to be described and it is estimated that the total diversity of the group will exceed 7,500 species worldwide. Many species of “Empididae” mate on the ground or on vegetation while others gather in mating swarms. The synchronized movement of adult flies within these mating swarms is the basis for the common name “dance flies”. Members of one large subfamily, the Empidinae, transfer nuptial gifts from male to female during courtship and mating. Depending on the species, these gifts include prey, various types of inedible objects, or secreted ‘balloons’ (Fig 3). Within the Empidinae mate, choice is generally by females that visit male-dominated swarms. However, many species exhibit sex-role reversed courtship behaviour where females gather in swarms to await males that choose mates. These species exhibit many female secondary sexual characters used in courting males, such as enlarged wings, pinnate leg scales, and eversible abdominal pleural sacs. It is not easy to avoid concluding that these gatherings are analogous to human behaviour in dance halls.

Then there are the pre-human bizarre dances of birds-of-paradise. Young males inherit those dance steps from their fathers, then refine them through practice and watching adults. Less obvious but equally important are the watchful females. It’s ultimately their choices that decide which dances reach the next generation.

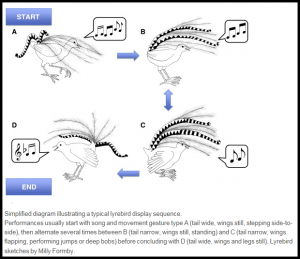

Fig 4 A song and dance performance in lyre birds.

Coordinating movements to music is often considered a uniquely human skill. A study of Australian lyrebirds dispels this notion by showing that male lyrebirds also perform ‘dance’ moves which are predictably matched with specific songs in an individual’s display routines. This involves the creation of the complex matching of subsets of songs from a individual bird’s extensive vocal repertoire with different but precise combinations of tail, wing and leg movements. The outcome is to form predictable ‘gestures’, and so appear to engage in intentional choreography (Fig 4). These dances also suggest that accurate synchronisation of the acoustic and locomotory elements of a display should be cognitively and physically challenging to achieve, and thus difficult to fake. If so, females might exercise mate choice by discriminating among males on the basis of integrated performance coordination. In terms of the coalition hypothesis a dancing lyre bird has been likened to a pop singer who combines song and dance to attract an audience of males and females. Male Birds of Paradise give similar displays which are viewed by potential mates but also by an audience of young male ‘learners’.

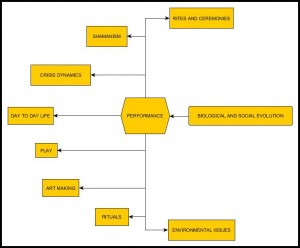

Physiological research suggests that humans have innate neurological specializations to combine music processing with patterns of muscular activity, and that special muscle-building genes determine the kinds of movements that different ethnic groups can achieve. The outcomes of these biological resources are to demonstrate to others who are interested how you get done what you do. Richard Schechner defines such activity as ‘performance’ (Fig 5). Performers of an assembly of humanitarian values are carriers, transmitters, and bearers of traditions, terms which connote a passive medium, conduit, or vessel, without volition, intention, or subjectivity.

Fig 5 Schechner’s categorisation of human performance

Performance has no character, plot, or action, and this distinguishes it from drama. In fact the concept of performance emerged during the last third of the 20th century and was part of a reaction against the predominance of western traditions in drama or theatre studies. Schechner explains that this approach can be applied to any event or material object. Performance takes everyday life as its stage and every form of human activity can come under its spotlight. From performance art to political rallies, to the law courts, religious ceremonies and sporting events, to simply dressing up for a night out on the town, the reach of performance studies is potentially limitless. In his 2003 book Performance Theory, Schechner dedicated a whole chapter to what he identified as the continuities between animal and human performance. Starting with a reference to Darwin’s view that there is a continuity of behaviour from animals to people, and driven by a desire to explore the question, “how are human religions, customs, and arts extensions, elaborations, and transformations of animal cultures?”, Schechner goes on to conclude that, “on several levels human and animal performances converge and/or exist along a continuum” manifested at different levels: structural, processual, technical, cultural, mimetic, and theoretical. However, rather than showing a primary interest in animal performance per se, Schechner calls for a study of the latter within performance theory solely as a strategy for better understanding their most evolved offspring, human performance.

However, a compelling account of the evolution of human musical and dancing abilities is lacking. The sexual selection hypothesis cannot easily account for the widespread performance of music and dance in groups, especially synchronized performances, and the social bonding hypothesis has severe theoretical difficulties. There is, however, a third evolutionary approach. This starts with the proposition that humans are unique among the primates in their ability to form cooperative alliances between groups in the absence of consanguineal ties. Edward Hagen and Gregory Bryan propose that this unique form of social organization is predicated on music and dance. In particular, they suggest that music and dance may have evolved as a coalition signalling-system that could, among other things, credibly communicate visually the intrinsic quality of a coalition, thus permitting meaningful cooperative relationships between groups. This capability may have evolved from coordinated territorial defence signals that are common in many social species, including chimpanzees.

In support of their theory Hagen and Bryan presented a study based on the idea that group performances are credible signals of collective interests. If most group members invested time and energy singing and dancing for visitors, the visitors might rightly conclude that the hosting group as a whole was strongly motivated to secure an alliance with them, whereas if only a small fraction of a large group bothered to do so, the visitors could rightly conclude the opposite. This argument has implications for the emotionality of music played in groups which the audience automatically classes as being good or bad . To test this, Hagen and Bryan set up an experiment in which manipulation of music synchrony significantly altered subjects’ perceptions of music quality. They found that the subjects’ perceptions of music quality were correlated with their perceptions of the coalition quality of the performers, supporting the coalition hypothesis. The hypothesis also has implications for the evolution of psychological mechanisms underlying cultural production in other domains such as food preparation, clothing and body decoration, storytelling and ritual, and tools and other artefacts.

In her paper ‘Music and Dance: Timeless Mediums in Uganda’, Katelin Gray paints an idealised picture of the role of dance in an emergent human culture where, “…. ancient agriculturalists and pastoralists linked hands and danced under the night sky, with soft drums beating syncopated rhythms in the background, and a flute made of bear bone emitting delicate melodies. The next day, most began sowing their millet and sorghum, while a few recorded the happenings of the night before on stone walls for us to find millennia later and consequently speculate about the meaning of art forms in prehistoric times”.

“Dancing and music were a means of education in a preliterate society and a method of unifying the different families that comprised the village. Music was more than entertainment; it reinforced and coordinated the community and connected the population through public activity”.

6 Dance in an ecological curriculum

Culture and society are not the same thing. While cultures are complexes of learned behaviours and perceptions, societies are groups of interacting organisms. People are not the only animals that have societies. Schools of fish, flocks of birds, and hives of bees are societies. In the case of humans, however, societies are groups of people who directly or indirectly interact with each other. People in human societies also generally perceive that their society is distinct from other societies in terms of shared traditions and expectations among its members..

While human societies and cultures are not the same thing, they are inextricably connected because culture is created and transmitted to others in a society. Cultures are not the product of lone individuals. They are the continuously evolving products of people interacting with each other. Cultural patterns such as language and politics make no sense except in terms of the interaction of people. In this respect, dance is a subset of the subject of culture.

Traditional forms of music and dance are of great historical value to current societies in revealing ethnic relations in a common past. Collectors of English folk songs knew this and composers such as Ralph Vaughan Williams have left a legacy of compositions which evoke times when most people laboured in the pre-industrial countryside.

In Africa, modern rulers fear the past; that an attachment to tribal kings, about whom much of the dance is performed, will weaken the political power of the wider state. Tribes are not considered a political entity with a legitimate head, but a lesser cultural institution. Yet tribal distinctions have been, and are still a powerful method of forming one’s identity. While political life eradicates this identity, traditional music and dance help to elevate it by communicating and affirming communally held morals and values and keeping active the accounts of a tribe’s history.

Peter Brinson, in his book ‘Dance As Education: Towards A National Dance Culture; sets out to answer the important questions, Why dance in the Curriculum? and In What Particular Way Does Dance Contribute to the Curriculum? Brinson believes we have a wealth of opportunities for cross curricular collaboration between the professional and educational dance worlds. In answer to the question ‘So what is next for dance?’ Brinson concludes that dance educators seek assurance that guidance will be given to planners of the school curriculum. Head teachers, however committed to the dance at present in their schools, will neglect it if clear statements are not made as to how and where dance may be included as a broad educational experience, with clear applications to day to day living in a global perspective where consumerism is seen as the antithesis of dance.

To establish a global curriculum, the proposition is that first and foremost, dance is an expression of the concept of ‘cultural ecology’, which has been used in the discipline of anthropology since the 1950s; it means the study of human adaptations to social and physical environments. In this context, dance makes a distinctive contribution to education at all levels in that it uses the most fundamental mode of human expression- movement to match individuals to their ecological niche.. The body as the instrument of expression is unique in its accessibility. Together with the other arts it provides considerable potential for the expression of personal and universal human qualities. Through its use of non-verbal communication, dance gives students the opportunity to participate in cross-curricular themes in a way which differs from any other area of learning. In a broad and balanced curriculum this important area of human experience should not be neglected.

7 Educational outcomes of dance

Brinson’s list of educational outcomes of dance are comprehensive and impressive.

Through artistic and aesthetic education, dance:

- provides initiation into a distinct form of knowledge and understanding.

- gives access to a unique expression of meaning.

- develops perceptual skills.

- develops the ability to make informed and critical judgments, develops creative thought and action.

- provides opportunities for creating and appreciating artistic forms.

- develops performance skills.

- introduces pupils to dance as a theatre art.

Through cultural education, dance:

- gives access to a rich diversity of cultural forms, offers insights into different cultural traditions, develops understanding of the different cultural dances attached to values

- introduces processes of cultural generation and change.

Through personal and social education, dance

- gives opportunities to explore the relationship between feelings, dance and expression.

- promotes sensitivity in working with others.

- develops self-confidence and pride in individual and group work.

- encourages independence and initiative.

- provides opportunity for achievement, success and self-esteem, for pupils with and without learning difficulties.

Through physical education, health and fitness education dance:

- promotes a responsible attitude to the body and its well-being, develops coordination, strength, stamina and mobility, encourages physical confidence and control, provides a leisure pursuit for fitness in life after school curriculum.

Environmental education is an important addition to to Brinson’s list.

Through environmental education, dance:

- students learn how to use the elements of dance and composition to convey a message about an environmental issue.

- students learn about one environmental issue through research and, in small groups, create a dance piece that advocates for community action to gain environmental betterment.

- students begin to understand and become aware of the various issues that we as a global interacting population are faced with, and through the use of an environmental artefact or source as inspiration, generate movements individually and in small groups with a particular environmental issue in mind.

Fig 6 Black Creek community performance

Regarding conservation as a return to humanitarianism, we already have the tools for dealing with environmental decline—they are innate to humans: awareness, free will, creativity and ingenuity. The issue is whether we are willing to use these abilities to build a better future. To date, we have used our intelligence to try to understand the world and human existence, to prolong our lifespans and improve our lifestyles, to become richer, and to assemble ourselves into groups and societies. We have developed the disciplines of science, philosophy, medicine, economics, politics, engineering and technology, but we have failed utterly to apply these effectively and consistently to deal with environmental issues. As a result, our behaviour as a species is little different from other animals whose destinies are determined by ecological laws.

Nevertheless, the environmental theme of dance was taken up by Laura Reinsborough and Liz Forsberg while studying community arts at the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University, Toronto. They created the Black Creek Storytelling Parade, a public performance that follows the route of storm water from a permeable surface of the university campus down to the banks of an ancient topographical feature known as Black Creek (Fig 6). They employed costumes, fanfare, amplification, and percussion— performance tactics to relate people to the hidden campus landscape. As organizers of the parade, they sought out a variety of interpretative questions and frameworks. The following narrative includes Reinsborough’s combination of description and interpretation relating to the performance. After the initial presentation, they continued as developers and coordinators in response to additional invitations to perform the Parade.

“As we critically reflect upon our practices and build upon past experiences, each performance has taken on new qualities and become increasingly more community-based. Throughout the development of the project, we have also used a number of different methods to attract attention (e.g., sidewalk chalk, costumes, percussion instruments, and audience participation), and we have altered those methods to attract different kinds of attention (e.g., letting go of the costumes after some joking comments from passers-by). Thus, we made decisions about our methods for their potential to both engage and alienate. Critically questioning our methods has been a part of our work each step of the way, out of an interest to hone our practices and as a result of our academic location as graduate students”.

“While York seemingly displays a barren landscape that obscures any history other than the corporate and colonial names of its buildings, we heeded advice from Planet U: Sustaining the World, Reinventing the University: “Dig a little, and any suburban campus has remnant roots with stories to tell”. And so we dug, using archival research and word of mouth to reveal the area’s unofficial stories: unsettled land claims, hidden community gardens, the historical presence of the passenger pigeon (a foreboding icon of species extinction), ecological restoration initiatives, and land use planning”

Their aim was to craft a multi-perspective view of Black Creek that would engage participants beyond a single, seemingly monolithic narrative. They invited storytellers and other keepers of knowledge to share their stories. The intent was to reach beyond the limits of their primary research, beyond the official stories proliferated by York University, and beyond the most common narratives told of nature and ecology. They hoped to inspire a social connection between parade-goers and place, to uncover the existing stories of the area and graft their own cultural meaning onto the campus landscape. The local coalition they created is a practical contribution to place-making.

8 Propositions for teaching and researching dance

Dance has its biological roots in pre-human evolution. Theatre practitioner Richard Schechner notes a link between the biological and its universal expression in human behaviour patterns:

“I confess that I believe both in universals and singularities. How can that be? In a nutshell, biology provides humans with templates, building blocks, integers (you pick your term, your metaphor), while culture and individuality determine how these are used, subverted, applied, and “made into” who each person and each social unit is. For me, there are realities at all levels of the human endeavour; biological–evolutionary, cultural–social, individual. These overlap and interplay. To assert a connection between the ethological, the anthropological, and the aesthetic is not to deny local and individual variation and uniqueness”.

It should be a matter of some interest and concern to those who teach and research humanistic studies such as the philosophy of dance that their work is founded on a heritage of philosophical speculations about the nature of knowledge and the mind. This was formulated by prehistoric people who had no reason to suspect that human consciousness and mental activity have had a long evolutionary history. Today, most branches of philosophy continue their investigations without regard for the implications of two centuries of palaeo-anthropological discoveries. These research findings imply that the human mind is of a remote antiquity and that it has evolved (and is evolving) within certain biological limits. The varied abilities that have emerged through natural selection have, necessarily and primarily, been of importance to humankind’s survival as a species.

Aesthetics is one of the branches of Western philosophy that has generally, even resolutely, held itself aloof from scientific encroachment or scrutiny. This process of Western thinking about art resists methods of science such as categorization, definition, or precise measurement. Its complex workings, whether of construction or appreciation, are regarded, non scientifically as being private, unobservable and usually fleeting, and therefore do not lend themselves to scientific perusal. However, viewing dance from the perspective of biological evolution is not the same thing as subjecting it to scientific analysis. More accurately, taking an evolutionary stance is part of a way of looking at art as a human behaviour, based on the assumption that human beings are a species of animal like other living creatures, which further implies that their behaviour like their anatomy and physiology has been shaped by natural selection. Such a viewpoint may suggest new avenues for thinking about some of the problems with which aesthetics has traditionally been concerned: the nature, origin, and value of art, not as an abstraction, but as a universal and intrinsic human behavioural endowment. Remember, evolution is the root of dance as a coalition-forming behaviour..

Speaking in evolutionary terms, it has only been in the blinking of an eye, that art has been detached from its evolved affiliates, ritual and play, and its various components have coalesced to become seen an independent activity. Until less than a hundred years ago the primary tasks of dancers, like painters, were not to “create works of art” but to reveal or embody the divine, illustrate holy writ, enrich shrines and private homes and public buildings. Like the, fashioning of fine utensils and elaborate ornaments accompany ceremonial observances, recording historic scenes and personages, and so forth, the makers made these things “special,” Specifically aesthetic considerations were no more relevant than other functional requirements.

The ways in which meaning was apprehended by our ancestors were not divided into separate entities called “art,” ‘science/’ “metaphysics.” Our attribution of the name “art” to tribal singing or dancing or to cave paintings is arbitrary and misleading. More simply, these are ways of ‘the mind in the cave’ of finding meaning in life, ways that were inextricably bound to social institutions and practices whose fundamental assumptions are no longer accepted unquestioningly. Evolution has set limits to human capabilities and in order to understand these it is necessary to collect and compare examples of universal human behaviours from many societies. Accounts from anthropological studies of a wide variety of human groups show that in spite of a wide diversity of detail, human beings universally display certain general features of behaviour which ethologists have identified in most animal societies as well. For example, both human and animal societies tend to form and maintain some kind of social hierarchy. Both humans and animals (including reptiles, birds, and even insects) use ritualized non-auditory communicatory signals that formalise emotional responses, channel aggression and reinforce social bonds to behave collectively. It is within this developing knowledge framework that dance links ethology, anthropology and aesthetics to provide an antidote to Kruk’s magic spell of world development that has ‘shifted humanitarian values to the background’. It is an evolved propensity to promote the development of behavioural coalitions which includes much more than theatre, but is expressed along an entire spectrum, ranging from everyday life to rituals and art.

It was inevitable that in our current digital age that there would be a move to integrate digital imagery with live performance. Over recent years that has become increasingly common with several artists creating work that enmeshes digital and biological performance entities within a performance context. The works draw on a range of technologies, from interactive and motion tracking systems to registered projected video, motion capture, 3D scenographic landscapes and more, all exploiting the possibilities of emergent technologies. The scope of dance is not narrowing towards digital, rather, it is expanding.”

In 2014, artists at the Deakin Motion.Lab premiered ‘The Crack Up’, a new full-length trans-media dance work Inspired by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1936 short story of the same name. Trans-media dance is defined here as a live performance in which both the digital and human presenters perform simultaneously as artistic equals.. The notion behind this work is that two people, or two or more performance entities, are splitting the attention of the audience, operating as equal collaborators in a holistically produced performance context. A mobile app was created for the performance which splits the direction of audience focus between a 3D video screened on stage, the dancers on stage, and the integrated mobile devices of members of the audience. The app provides poetic images and lines of text. This transmedia performance can be taken as the starting point for research into the potential for augmenting live performance with 3D projected scenography and mobile devices. It is also a starting point for discussion on the potential for dramaturgy, choreographic process, and the directing of audience attention within trans-media dance performances.

9 Climate change: a challenge for community performance

http://ec.europa.eu/clima/citizens/youth/docs/youth_magazine_en.pdf

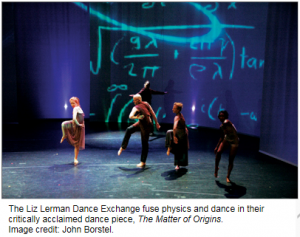

The dancer, Liz Lerman, finds science to be a rich source of material for her dance company to perform; she sees her dancers as helping disseminate scientific discoveries to the public, and helping the public visualize the scientific concepts. There is part of a current trend for dance companies to choreograph dances about molecular genetics, with themes such as the Genome Project and DNA replication. Nobel laureate John Polanyi has referred to molecular movement as “the dance of the molecules.” On the other side, many scientific discoveries are often an inspiration for dancers, actors, playwrights, poets and musicians. Indeed, physics provides the intellectual framework for one of Lerman’s works, on which the whole piece hangs. For one hour, dancers young and old, spin, leap, fall, balance and re-balance through critical moments of atomic and subatomic history referencing Marie Curie and the discovery of radium, the Manhattan Project, the particle collider at CERN and the Hubble telescope (Fig 7).

Fig 7 A fusion of physics and dance

Today, the greatest need for the general public to engage with science is the global threat to humanitarian values known as ‘climate change’. Without doubt, scientific evidence is telling us that:

- the global climate has been changing over the several decades in a manner that is highly unusual compared to a very long history of climatic stability;

- emissions of greenhouse gases, mostly carbon dioxide from humanity’s use of fossil carbon fuels are the dominant cause of these changes;

- these changes are already having significant adverse impacts on human well being and on ecosystems;

- this harm will continue to grow unless the offending emissions are greatly reduced.

For future generations to cope with the accompanying environmental instabilities there has to be a big behavioural change in order to live within a balanced carbon economy, where our emissions match the rate at which they can be taken out of the atmosphere . This is the most relevant, important and continuous message for educators to transmit, using every available means and media, at all levels of education. The slogan is ‘Our Planet Our Future: Fighting Climate Change Together’. This is the title of a booklet produced by the European Commission in 2015. Miguel Canete in his foreword says:

“Climate change is one of the greatest threats facing mankind today. It is not a problem we can put off and deal with when we have more time or more money. We all have a duty to act to stop the climate getting worse, The actions we take now will determine what the world we live in will look like in 10, 20 or 50 years’ time. And it’s going to to need huge efforts from all of us individuals, governments, businesses, schools and other organisations, working together for a better climate and better future”.

The message is that the objective of climate action is to impart sustainability and resilience to world development. In other words, dealing with climate change has become the basis of our common humanity and as such climate action should become a major pillar of education. ‘Working together’ means networking globally; ‘actions’ means making betterment plans, with realistic targets, in homes, neighbourhoods, schools and workplaces, The outcome is to leave smaller carbon footprints for future generations to follow.

Documentation of the urgent need for action plans to mitigate or adapt to climate change runs from 1988 to 2014. To present its call for action needs more effective communication. The difficulty in teaching climate change using traditional bookish methods is that we can’t think about it in a linear manner. Our thoughts about it bounce off other thoughts like a ping-pong ball. They go in all possible directions. Therefore, the best way to keep track of thoughts about a subject like climate change that conforms to a cross-curricular framework is by the application of a whole range of the brain’s cortical skills to make and respond to mind maps.

Mind maps are resources for visual learning and dance is a powerful visual medium that links culture with ecology. The thinking skills of choreography include; logic, rhythm, lines, colour, lists, daydreaming, numbers, imagination, word, and seeing the whole picture. The more these activities are integrated, the more the brain’s performance becomes co-operative, with each intellectual skill enhancing other intellectual areas.

When navigating the mind map of a dance the audience is not only practicing and exercising their fundamental powers of memory and information processing, but are also using their entire range of cortical skills with all the elements that the brain can process.. This is spiced up with personal elements like imagination, association and location which make learning absorbing and effective.

This then is the challenge for those wishing to present climate change as an educational performance. The aim is to dispel the following five myths about the underlying science

- The Earth stopped warming in the last decade.

- If it is warming, humans aren’t the main cause.

- A little warming isn’t harmful anyway.

- If there is any danger, it’s far in the future.

- Even if mainstream climate science is right and the need for action therefore is real, doing enough to make a difference is unaffordable.

With or without dance, making a mind map is an educational performance, because teaching climate change is primarily a process of cross-subject storytelling, For example, the Bella Gaia performance is a fine, albeit expensive, example of life-changing dance and music messaging. Inspired by astronauts who spoke of the educative power of seeing the Earth from space, filmmaker and composer Kenji Williams created the award winning Bella Gaia as a trans media performance that successfully simulates space flight, taking the audience on a spectacular journey around the planet Earth. It showcases a thought-provoking stream of crucial scientific data regarding our imperilled ecosystems while also celebrating the amazing cultural heritage of humanity.

At the other end of the scale, the European Commission’s booklet also aims to produce behavioural change. In this respect it provides ideas, facts and imagery for communities to choreograph a variety of performances, with or without transmedia components, presenting important international issues about climate action and relating them to local situations.

Above all, a dance performance thoughtfully combined with social media allows people to share what is learned with the world and tap into the knowledge and experience of others to help make even stronger connections with real-world problems and their solution (Fig 8)

Fig 8 A performance for raising awareness of the need for climate action (New York:2014)

https://www.imperial.ac.uk/grantham/news-and-events/past-events/public-lectures–seminars/

9 Web references

Models

http://doursat.free.fr/docs/CS790R_S05/CS790R_S05_Flocking_Schooling.pdf

https://www.princeton.edu/pr/news/05/q1/0203-flock.htm

http://www.sekj.org/PDF/anzf19/anz19-081-085.pdf

http://www.nadsdiptera.org/Doid/Empidchar/Empidchar.htm

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982213005721

People dancing

Definition of performance

http://www.icosilune.com/2009/01/richard-schechner-performance-theory/

http://wn.com/richard_schechner

Academic view

http://www.xavier.edu/xjop/documents/gray.pdf

Art as human behaviour

http://www.ellendissanayake.com/publications/pdf/EllenDissanayake_5618127.pdf

Environmental education through community arts

http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ842768.pdf

Music

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Uganda

Cultural values

http://www.academia.edu/1937342/Ugandan_Traditional_Cultural_Values

Social dance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_dance

http://www.bellagaia.com/about.html

Cross curricular view

Cultural ecology

http://www.publicartonline.org.uk/downloads/news/AHRC%20Ecology%20of%20Culture.pdf

Folklore Jessica Schmonsky

http://www.ecology.com/2012/10/24/ecological-importance-folklore/

Beauty and behaviour intertwined

www.birdsofparadiseproject.org

Biocultural musings

http://bioculturalmusings.blogspot.co.uk/2010/01/biology-of-dance.html

Both information and social cohesion determine collective decisions in animal groupshttp://www.pnas.org/content/110/13/5263.full

Music and dance as a coalition signaling system

http://cogprints.org/2472/1/music.pdf

Ecological dominance; social competition

http://jayhanson.us/_Biology/Social_Arms_Race.pdf

A doctoral thesis

http://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/5011/1/Cook20125011.pdf

Climate action

1 Action for trees

2 Economic action

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/11/magazine/11Economy-t.html?_r=0

3 Milestones

Transmedia dance performance

http://isea2015.org/proceeding/submissions/ISEA2015_submission_53.pdf

Science of chemistry and dance

http://old.iupac.org/publications/cei/vol6/11_Lerman.pdf

Intangible heritage

http://www.nyu.edu/classes/bkg/web/heritage_MI.pdf

Learning ecologies

http://www.lifewideebook.co.uk/uploads/1/0/8/4/10842717/chapter_a5.pdf

Conservation, human values and democracy