Those now being educated will have to do what we, the present generation, have been unable or unwilling to do: stabilise world population; stabilise and then reduce the emission of greenhouse gases; protect biological diversity; reverse the destruction of forests everywhere; and conserve soils. They must learn how to use energy and materials with great efficiency. They must learn how to utilise solar energy in all its forms. They must rebuild the economy in order to eliminate waste and pollution. They must learn how to manage renewable resources for the long run. They must begin the great work of repairing as much as possible, the damage done to Earth in the past 200 years of industrialisation. And they must do all this while they reduce worsening social and racial inequities. No generation has ever faced a more daunting agenda”. (Orr, 1994, p.26).

1 A conservation management curriculum

The general definition of economic sustainability is the ability of an economy to support a defined level of economic production indefinitely. This can only be achieved as a long term international goal if humankind takes from Earth only what its ecosystems can provide indefinitely. This kind of economy, which recognises Earth’s ecological limits, can be called a natural economy in that it can only be established by moral certainty or conviction. Whilst accepting that science is the engine of prosperity there is now general agreement within the international community that humanity must move towards a natural economy where production is aimed at satisfying the consumer’s own needs, and is not driven by wants. The former would include the needs for food, clothing, shelter and health care. Wants are goods or services that are not necessary but that we desire or wish for. Education has to change accordingly. In particular it has to emphasise the need to share Earth’s resources and gradually embrace the need to integrate the principle of sharing per se into our international economic and political structures. The mantra of natural economy is ‘prosperity without growth’.

Most educationalists would recognised that Orr’s ‘conservation management curriculum’ should be at the centre of education at all levels, but it is still a peripherally rare and optional system of education.

In Wales during the 1970s, natural economy emerged as the idea for a new academic subject from student/staff discussions during a zoology field course on the Welsh National Nature Reserve of Skomer Island in 1971. It was enthusiastically taken up as the philosophical thread for an honours course in Environmental Studies organised in the University College of Wales, Cardiff, during the 1970s. This course integrated the inputs from eleven departments, from archaeology, through metallurgy, to zoology.

Late in the decade this course was evaluated by a group of school teachers under the auspices of the University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate (UCCLES), and emerged as the subject ‘natural economy’ (the organisation of people for production). Natural economy was launched as a new international subject by UCCLES to fulfil their need for a cross-discipline arena to support world development education. UCCLES was urged in this direction by the Duke of Edinburgh, who was chancellor of the university at this time.

Natural economy was disseminated throughout Europe as part of the EC’s Schools Olympus Broadcasting Association (SOBA) for distance learning. It was also published as a central component of a cultural model of Nepal through a partnership between the University of Wales, the UK Government Overseas Development Administration and the World Wide Fund for Nature, with a sponsorship from British Petroleum.

During the 1980s, an interoperable version of natural economy for computer-assisted learning was produced in the Department of Zoology, Cardiff University, with a grant from DG11 of the EC. This work was transferred to the Natural Economy Research Unit (NERU) set up in the National Museum of Wales towards the end of the decade.

2 Culture and ecology

The complex interdependencies that shape the demand for and production of arts and cultural offerings is defined as the ecology of culture. Culture is often discussed as an economy, but it is better to see it as an ecology, because this viewpoint offers a richer and more complete understanding of people’s behaviour. Seeing culture as an ecology is congruent with cultural value approaches that take into account a wide range of non-monetary values. An ecological approach concentrates on relationships and patterns within the overall system, showing how careers develop, ideas transfer, money flows, and product and content move, to and fro, around and between the funded, homemade and commercial subsectors. Culture is an ‘organism’ not a mechanism; it is much messier and more dynamic than linear models allow. The use of ecological metaphors, such as regeneration, symbiosis, fragility, positive and negative feedback loops, and mutual dependence creates a rich way of discussing culture and its relationships to environment. Different perspectives of culture then emerge, helping to develop new taxonomies, new visualisations, and fresh ways of thinking about how culture operates.

In the 1990s NERU obtained a series of grants to integrate natural economy into a broader knowledge framework linking culture with ecology. This wider social framework was called cultural ecology. For example, an EC LIFE Environment programme with the aim of producing and testing a conservation management system for industries and their community neighbourhoods, used cultural ecology as the wider knowledge framework.The work was carried out in partnership with the UK. Conservation Management System Consortium (CMSC www.esdm.co.uk/cms), the University of Ulster and British industry.

Version 2 of cultural ecology on-line was developed and evaluated by the ‘Going Green Directorate’ with the aim of giving the subject a wider international significance. One aim was to provide a web resource for education/training in conservation management. The other aim was to develop an education network based on the production of educational wikis to bring conservation management towards the centre of curricula at all levels of education.

Version 3 of Cultural Ecology became part of International Classrooms on Line financed and promoted by the charitable Bellamy Fund.

3 MEA: an educational framework

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was carried out between 2001 and 2005 to assess the consequences of ecosystem change for human well-being. The practical aim was to establish the scientific basis for actions needed to enhance the conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems and their contributions to human well-being. The MEA responded to government requests for information received through four international conventions—the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, and the Convention on Migratory Species. It was designed to also meet needs of other stakeholders, including the business community, the health sector, nongovernmental organisations, and indigenous peoples. Sub-global assessments were aimed to meet the needs of users in the regions where they were undertaken.

The assessment focuses on the linkages between ecosystems and the cultural dimension of human well-being and, in particular, on “ecosystem services.” An ecosystem is a dynamic complex of plant, animal, and microorganism communities with the nonliving environment interacting as a functional unit. The MA deals with the full range of ecosystems—from those relatively undisturbed, such as natural forests, to landscapes with mixed patterns of human use, to ecosystems intensively managed and modified by humans, such as agricultural land and urban areas.

Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from natural economy in its functional sense. These benefits include provisioning services such as food, water, timber, and fibre; regulating services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits, and supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling Humanity, while buffered against environmental changes by culture and technology, is fundamentally dependent on the flow of ecosystem services.

The MEA examines how changes in ecosystem services influence human well-being. Human well-being is assumed to have multiple constituents. These include the basic material for a good life, such as-

- secure and adequate livelihoods;

- enough food at all times;

- shelter, clothing, and access to goods;

- health, including feeling mentally well and having a healthy physical environment, such as clean air and access to clean water;

- good social relations, including social cohesion, mutual respect, and the ability to help others and provide for children;

- security, including secure access to natural and other resources, personal safety, and security from natural and human-made disasters;

- and freedom of choice and action, including the opportunity to achieve what an individual values doing and being.

Freedom of choice and action is influenced by other constituents of well-being (as well as by other factors, notably education) and is also a precondition for achieving other components of well-being, particularly with respect to equity and fairness. This raises the questions how should ‘prosperity’ be redefined and how could prosperity be spread without economic growth?

The conceptual framework for the MEA posits that people are integral parts of ecosystems and that a dynamic interaction exists between them and other parts of ecosystems, with the changing human condition driving, both directly and indirectly, changes in ecosystems and thereby causing changes in human well-being. At the same time, social, economic, and cultural factors unrelated to ecosystems alter the human condition, and many natural forces influence ecosystems.

Although the MEA emphasizes the linkages between ecosystems and human well-being, it recognizes that the actions people take that influence ecosystems result not just from concern about human well-being but also from considerations of the intrinsic value of species and their ecosystems. Intrinsic value is the value of something in and for itself, irrespective of its utility for someone else. The MEA therefor probides the pedagogy for cultural ecology.

http://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf

4 Well-being

Freedom and choice refers to the ability of individuals to control what happens to them and to be able to achieve what they value doing or being. To be able to have freedom of choice and action people have to be in a state of well-being. Well-being is not just the absence of disease or illness. It is a complex combination of a person’s physical, mental, emotional and social health factors. Well-being is strongly linked to happiness and life satisfaction. In short, well-being could be described as how you feel about yourself and your life. Everyone has freedom of choice and action as their goal in life. Freedom and choice cannot exist without the presence of all the elements governing well-being,

Social surveys have defined five distinct statistical factors which are the universal elements of well-being that differentiate a thriving life from one spent suffering. They describe aspects of our lives that we can do something about and that are important to people in every situation studied.

http://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/126884/five-essential-elements-wellbeing.aspx

These elements do not include every nuance of what’s important in life, but they do represent five broad categories that are essential to most people.

- The first element is about how you occupy your time or simply liking what you do every day: your Career Well-being.

- The second element is about having strong relationships and love in your life: your Social Well-being.

- The third element is about effectively managing your economic life: your Financial Well-being.

- The fourth element is about having good health and enough energy to get things done on a daily basis: your Physical Well-being.

- The fifth element is about the sense of engagement you have with the area where you live: your Community Well-being.

5 Ecosystem Services

People everywhere rely for their well-being on ecosystems and the services they provide. So do businesses. Demand for these services is increasing. However, many of the world’s ecosystems are in serious decline, and the continuing supply of critical ecosystem services is now in jeopardy. The global economy is nearly five times the size it was fifty years ago. This unprecedented level of growth places huge demands on limited resources and has degraded an estimated 60 per cent of global ecosystems. The loss or degradation of ecosystem services will have increasing impacts on human well-being.

There is an indirect influence of changes in all categories of ecosystem services on the attainment of this constituent of well-being. The influence of ecosystem change on freedom and choice is heavily mediated by socioeconomic circumstances. The wealthy and people living in countries with efficient governments and strong civil society can maintain freedom and choice even in the face of significant ecosystem change, while this would be impossible for the poor if, for example, the ecosystem change resulted in a loss of livelihood.

In the aggregate, the state of our knowledge about the impact that changing ecosystem conditions have on freedom and choice is severely limited. Declining provision of fuelwood and drinking water have been shown to increase the amount of time needed to collect such basic necessities, which in turn reduces the amount of time available for education, employment, and care of family members. Such impacts are typically thought to be disproportionately experienced by women.

The common elements that underlie poor people’s exclusion are voicelessness and powerlessness. Research conducted by the World Bank in 1999, involving over 20,000 poor women and men from 23 countries, concluded that despite very different political, social and economic contexts, there are striking similarities in poor people’s experiences. The common theme underlying poor people’s experiences is one of powerlessness. Powerlessness consists of multiple and interlocking dimensions of ill-being or poverty.

Confronted with unequal power relations, poor people are unable to influence or negotiate better terms for themselves with traders, financiers, governments, and civil society. This severely constrains their capability to build their assets and rise out of poverty. Dependent on others for their survival, poor women and men also frequently find it impossible to prevent violations of dignity, respect, and cultural identity.

In its broadest sense, empowerment is the expansion of freedom of choice and action. It means action to increase one’s authority and control over the resources and decisions that affect one’s life. As people exercise real choice, they gain increased control over their lives. Poor people’s choices are extremely limited, both by their lack of assets and by their powerlessness to negotiate better terms for themselves with a range of institutions, both formal and informal. Since powerlessness is embedded in the nature of institutional relations, in the context of poverty reduction an institutional definition of empowerment is appropriate.

The economic history of the world is the entire history of the world, but seen from a certain vantage-point – that of the economy. The ecological history of the world is the history of the world seen from an environmental viewpoint. Increasingly, this environmental viewpoint takes in the place of the human ecosystem within the entire cosmos. To choose one or other vantage-point, and no other, is of course to favour from the start a one-sided form of explanation. However, economists and historians have stopped thinking of economics as a self-contained discipline and of economic history as a neatly-defined body of knowledge, which one could study in isolation from other subjects. Economic phenomena cannot be properly grasped by economists unless they go beyond the economy. With regard to political economy, which in the 19th century appeared to concern only material goods, it has turned out to embrace the social system as a whole, being related to everything in society. The same can be said of biologists with respect to ecology, with its history of evolution, which is no longer regarded as primary science, but as a philosophy of inter-relatedness.

Political culture is an important variable in the analysis of cultural ecology as it suggests underlying beliefs, values and opinions which people hold dear (such as shared ethnic and religious affinities) and that produce culturalistic groups. For example, catholicism treats the individual as social and transcendent.

‘Ecology’ is used to define a particular type or branch of the relationship between living organisms and their environment e.g. aquatic ecology; avian ecology. Where the species is a community of Homo sapiens, sharing a common heritage of ideas, beliefs values and knowledge, the interrelationship is called cultural ecology. It includes an environmental complex of human activities undertaken for profit. The activities are concerned with the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services and the management of natural resources (land, forest, water), finances, income, and expenditure of a community, business enterprise, etc. This highlights the fact that the subject matter of both ecology and economics, which are themselves interrelated, cannot be isolated from all the other social, ideological and political problems of survival.

Economics and ecology come together at their common linguistic root , oikos; house, which in both cases signifies a space where a complex of activities is undertaken concerned with the consumption of natural resources and their transformation for production and distribution.

Management and ecology, as a specific pattern of human activities, emerges in the archaic use of the word economy to define the management of household affairs; (via Latin from Greek oikonomia; domestic management, from oikos house + -nomia, from nemein to manage)

Keeping Within Earth’s Ecological Limits

6 An educational framework

Cultural ecology is a system of knowledge about environmental management. It has been created in Wales from the inputs of teachers and students at all levels of education. The aim is to stimulate discussion of ideas and projects about how to bring people and nature into equilibrium. The approach is through planning for sustainability based on good science and robust economics in which well-being of our planet and personal beliefs are interdependent.

The following definitions are provided to guide its use and development as an interdisciplinary educational framework.

- Cultural ecology provides windows from many subjects into issues of environmental management.

- Cultural ecology is about human communities as makers. In making things, humans are now the main functional components influencing planet Earth’s biological cycles of materials and energy flows.

- Cultural ecology is an educational experience that demonstrates the importance of crossing boundaries of traditional subjects in order to understand and solve environmental problems.

- Cultural ecology is a practical activity. It shows how individuals, families, and organisations can make and operate action plans to set limits on the environmental impact of their day to day uses of materials and energy that flow through home, neighbourhood, workplace and leisure environment.

- Cultural ecology is a set of notions about nature illustrating how everyone interprets the world from within a particular multi factorial framework of perception and thought. This often gives rise to difficulties and dangers in using one’s own perspective to judge the values and behaviour of others towards environmental issues.

- Cultural ecology is seen practically as a gathering of local information about the good and bad aspects of neighbourhood, put into a global context. It provides a knowledge framewwork for environmental appraisal, which is necessary for citizens to participate constructively in local government plans for sustainable development- the Local Agenda 21- and the 2030 targets for living sustainably, particularly in the context of community regeneration.

- Cultural ecology empphasises the environmental relationships between poverty, social exclusion and the environment. Urban environments are often characterized by overcrowding, substandard housing, underemployment,une mployment and an undeveloped infrastructure, especially in relation to the provision of basic social services. Rural environments are frequently characterized by social exclusion resulting from landlessness, inequitable land-tenure systems, subsistence or lower incomes, and paucity of basic social services. Both create their own particular versions of poverty and deprivation which constitute a major challenge to governments and agencies in the provision of a reasonable living environment

To bring conservation management to the heart of family life requires an ability in each individual to conceptualise the wholeness of self and environment as a set of beliefs to live by and a context that gives meaning to life. This ability may be described as ecosacy; a third basic ability to be taught alongside literacy and numeracy. The term ecosacy comes directly from the Greek oikos meaning house, and household management includes making decisions about the natural resources that flow into it. To be ecosate means having the knowledge and mind-set to act, speak and think according to deeply held beliefs and belief systems about people in nature, which is conceptualised as a community of beings.

The educational framework of ecosacy is cultural ecology. The division of knowledge has its origin in the work of Steward in the 1930s on the social organization of hunter-gatherer groups. Steward argued against environmental determinism, which regarded specific cultural characteristics as arising from environmental causes. Using band societies as examples, he showed that social organisation itself corresponded to a kind of ecological adaptation of a human group to its environment. He defined cultural ecology as the study of adaptive processes by which the nature of society and an unpredictable number of features of culture, are affected by the basic adjustment through which humans utilise a given environment in which they have inevitably become an ecological component.

Cultural ecology, as a divsion of science, originated from an ethnological approach to the modes of production of native societies around the world as adaptations to their local environments. It has long been accepted that this anthropological view is too narrow. It isolates knowledge about the ancient ways of resource management from possible applications to present day issues of globalised urban consumerism. People now consume resources at a considerable distance from where they occur. Conservation management is an institutional process of political adaptation to the environmental impact of world development. Conservation systems are concerned with stabilising the functional relationships between people and the environment, and managerialism has to be integrated into people’s perceptions of how they fit within environmental systems, large and small.

Because traditional systems often involve long-term adaptations to specific local environments and resource management problems on their doorsteps, they are of interest to resource managers everywhere. Also, there are lessons to be learned from the cultural significance of traditional ecological knowledge with regard to the sometimes sacred dimensions of indigenous knowledge, such as symbolic meanings and their importance for cementing social relationships and values into the neighboorhood..

If conservation management is to be brought into the general education system from its current specialized professional periphery, it has to have cross-topic connections for learners to navigate to and from a range of departure points.

A mind-map to begin building this navigation system was produced from the subject of ‘natural economy’ created by the Cambridge University Examination Syndicate for education in world development. This project was carried out by the Going Green Directorate, a group of academics and teachers associated with the Schools and Communities Agenda 21 Network of the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff.

http://www.culturalecology.info/page2.html

Cultural ecology presents two sides of the coin of global economic development. World development has taken place by the ‘unlocking of nature’, at first by self-sufficient groups in bands, and tribes. Now it involves networks of interdependent nations involved in industrial mass production and the movement of resources and goods rapidly over vast distances measured in hours or days. This process has taken place not by biological evolution, but by inventions, which, from age to age, drive the human economic system. First it involved the application of ideas about the living world that produced the hunter and the forager, and led to fire and water being harnessed as physical aids to comfort and lighten labour. From these beginnings came a settled view of ‘nature’ as something to be subdued by mankind. This led to the development of educational systems in which subjects were built according to the knowledge required to educate the specialists who were to carry forward this exploitative culture.

A new educational map is now needed to replace the fragmented one that has been shaped by the industrial revolution and that is now leading inexorably toward the destruction of industrial society. Industrial humankind now has to remake its culture globally and direct future cultural evolution for living sustainably. A rationally controlled technology does give us a means of survival for ourselves and many generations to come, although it must be supplemented by a social technology that encourages people to value and reward ecologically sound behavior and adopt a new values of what it means to be prosperous. Mankind must respond to survival imperatives with meaningful social action. Culture must again become an ally, rather than an enemy, in realising the sensible strategies for survival that were set out in the 1992 Rio Environmental Summit.

This new map for the 21st century and beyond carries the undercurrents of knowledge that flow between and into conventional subjects. Based on the MEA, it is an overview of the integration of knowledge required to produce an overview of the topics that have to be brought together to explain human cultural evolution and are needed to develop operations to balance our use of natural resources in relation to their continued availability. Subjects have been replaced by topics. Topics are the links between knowledge and action and are guideposts for a sustainable society. In the mindmap of cultural ecology it will be seen that traditional subjects, which are designed to produce specialists, are to be found three to four levels deep.

The topic map of cultural ecology presents world development as the replacement of traditional systems for utilising natural resources with scientific systems for managing imass productions. Conservation management is the bridge between these historical, interrelated aspects of human social evolution. It carries value judgments and perceptions about environment where scientific knowledge is not necessarily the clearest representation of what reality is from the standpoint of Homo sapiens being just one of many living things in a community of beings.

7 Flows of ideas for living sustainably

The two flows of ideas about cultural ecology begin with the major topics of ‘exploiting resources’ and ‘conserving resources’.

Viewed through the human economic system and its consequences, one set of second-level topics represent the exploitation of natural resources governed by people’s ideas about human production. This starts with knowing how to tap resources for making goods. Cultures are formed. When basic survival needs have been met, ‘making things’ is accelerated by creating public and private art works, using earnings from ever demanding markets for goods and services. Civilizations are formed.

Today, demand for goods is now so great by all nations across the world that it is impacting on the limited stocks and the planets finite space, producing changes in culture, society and environment. The stocks and flows of nature’s production represent the intrinsic organisation for producing the resources we loosely call ‘natural”.

Conservation of natural resources takes place around ideas about how to cope with the impact of human production through concepts of culture, society and environment. The aim is to sustain production from generation to generation, by developing global culture committed to conservation strategies. The objectives have to be met through operational, outcome- based conservation management systems.

But following this flow of ideas, and agreeing with the conclusion that the present cultural attitudes towards the dominance of exploitation have to be moderated by conservation management in home and community, is not enough. The application of a new cultural ecology to living in an overcrowded world, chasing new goods and services, will ultimately depend on the actions of the majority in a democratic society. If each person fails to see, feel and act in relation to the long-term consequences of what he or she is doing, all will be lost. In the end, each person must be made to feel responsible for the present and future welfare of all mankind. Education can only become applied when its content corresponds to, or gives valid and acceptable guidance for dealing with reality.

Designing a new culture means adopting an activist attitude toward cultural evolution rather than passive acquiescence to the results of technology; but most important of all, it means actively intervening to modify norms, values, and institutions to bring them into line with the physical and biological constraints within which mankind must operate.

The entire world society must soon reach a consensus on what is meant by a livable world and must cooperate in using science, technology, and social institutions to construct that world, rather than forcing human beings to conform to a world shaped by these forces out of control.

8 Conservation Management

Conservation management is an applied aspect of cultural ecology To the extent that we have genuine respect for the natural world and the living things in it, the conflict between human civilization and the natural world is not an uncontrolled and uncontrollable struggle for survival. From an ethical standpoint, the competition between human cultures and the natural ways of other species can exemplify a moral order that can best be described as ‘live and let live’. To realise this order, we as moral agents have to impose constraints on our own lifestyles and cultural practices to create a moral universe in which both respect for wild creatures and respect for persons are given a place. The more we take for ourselves, the less there is for other species, but there is no reason why, together with humans, a great variety of animal and plant life cannot exist side by side on our planet. In order to share the Earth with other species, however, we humans must impose limits on our population, our habits of consumption, and our technology. In particular, we have to deal with serious moral dilemmas posed by the competing interests of humans and nonhumans. The problems of choice take on an ethical dimension but do not entail giving up or ignoring our human values. The aim is to manage situations in which the basic interests of animals and plants are in conflict with the non basic interests of humans.

Basic interests of humans are what rational and factually enlightened people would value as an essential part of their very existence as persons. They are what people need if they are going to be able to pursue those goals and purposes that make life meaningful and worthwhile. Their basic interests are those interests which, when morally legitimate, they have a right to have fulfilled. We do not have a right to whatever will make us happy or contribute to the realization of our value system, but we do have a right to the necessary conditions for the maintenance and development of our personhood. These conditions include subsistence and security (“the right to life”), autonomy, and liberty. A violation of people’s moral rights is the worst thing that can happen to them, since it deprives them of what is essential to their being able to live a meaningful and worthwhile existence as persons.

Our non-basic interests define our individual value systems. They are the particular ends we consider worth seeking and the means we consider best for achieving them. The non- basic interests of humans thus vary from person to person, while their basic interests are common to all.

The principles of conservation apply to two different kinds of conflicts in which the basic interests of animals and plants conflict with the non basic interests of humans. But each principle applies to a different type of non basic human interests. In order to differentiate between these types we must consider various ways in which the nonbasic interests of humans are related to the attitude of respect for nature.

First, there are non basic human interests which are intrinsically incompatible with the attitude of respect for nature. The pursuit of these interests would be given up by anyone who had respect for nature because the kind of actions and intentions directly embody or express an exploitative attitude toward nature. Such an attitude is incompatible with that of respect because it considers wild creatures to have merely instrumental value for human ends and denies the inherent worth of animals and plants in natural ecosystems. Examples of such non-basic exploitative interests and of actions performed are:-

- Slaughtering elephants so the ivory of their tusks can be used to carve items for the tourist trade.

- Killing rhinoceros so that their horns can be used as dagger handles.

- Picking rare wildflowers, such as orchids and cactuses, for one’s private collection.

- Capturing tropical birds, for sale as caged pets.

- Trapping and killing reptiles, such as snakes, crocodiles, alligators, and turtles, for their skins and shells to be used in making expensive shoes, handbags, and other “fashion” products.

- Hunting and killing rare wild mammals, such as leopards and jaguars, for the luxury fur trade.

- All hunting and fishing, which is done as an enjoyable pastime (whether or not the animals killed are eaten), when such activities are not necessary to meet the basic interests of humans. This includes all sport hunting and recreational.

All such practices treat wild creatures as mere instruments to human ends, thus denying their inherent worth. They are non basic. Wild animals and plants are being valued only as a source. Their central purposes represent an exploitative attitude towards nature. Those who participate to fullfil the aims of such activities as well as those who enjoy or consume the products knowing the methods by which they were obtained, cannot be said to have genuine respect for nature.

It should be noted that none of the actions violate human rights. Indeed, if we stay within the boundaries of human ethics alone, people have a moral right to do such things, since they have a freedom-right to pursue without interference their legitimate interests and, within those boundaries, an interest is “legitimate” if its pursuit does not involve doing any wrong to another human being.

It is only when the principles of environmental ethics are applied to such actions that the exercise of freedom-rights in these cases must be weighed against the demands of the ethics of respect for nature. We then find that the practices in question are wrong, all things considered. For if they were judged permissible, the basic interests of animals and plants would be assigned a lower value or importance than the nonbasic interests of humans. No one who had the attitude of respect for nature (as well as the attitude of respect for persons) would find this acceptable. After all, a human being can still live a good life even if he or she does not own caged wild birds, wear apparel made from furs and reptile skins, collect rare wildflowers, or engage in recreational hunting.

Conserving natural resources is about using less and managing stocks to ensure they are renewable and an even flow is carried forward into the long-term. This philosophy was endorsed by the international community in towards the end of the 1980s.

For example;

the Governing Council of UNEP, the UN Environment Programme, in its decision 15/2 of 1989, “invites the attention of the General Assembly to the understanding of the Governing Council with regard to the concept of “sustainable development”, as follows: “Statement by the Governing Council on Sustainable Development”

“Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs and does not imply in any way encroachment upon national sovereignty. The Governing Council considers that the achievement of sustainable development involves cooperation within and across national boundaries. It implies progress toward national and international equity, including assistance to developing countries in accordance with their national development plans, priorities and objectives. It implies, further, the existence of a supportive international economic environment that would result in sustained economic growth and development in all countries, particularly in developing countries, which is of major importance for sound management of the environment. It also implies the maintenance, rational use and enhancement of the natural resource base that underpins ecological resilience and economic growth. Sustainable development further implies incorporation of environmental concern and considerations in development planning and policies, and does not represent a new form of conditionality in aid or development financing.’ “—Official Records of the General Assembly, Forty-first Session, Supplement No. 25 (A/4425), UNEP/GC, 15/12 decision 15/2, Annex II.

9 Cultural Values

Culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behaviour acquired and transmitted between individuals and groups by symbols.

The behavioural patterns constitute the distinctive achievement of human groups, including their embodiments in artifacts. In this context, the essential core of culture consists of traditional ideas and especially their attached values, which govern the way the members currently use nature, live in nature and relate to their historical roots expressed in traditions of art , technology and landscape. Culture systems may, on the one hand, be considered as products of action, on the other hand, as conditioning value-influences upon further action.

Cultural ideas manifest themselves in different ways and differing levels of depth. Symbols represent the most superficial and values the deepest manifestations of culture, with heroes and rituals in between.

Symbols are words, gestures, pictures, or objects that carry a particular meaning, which is only recognized by those who share a particular culture. New symbols easily develop, old ones disappear. Symbols from one particular group are regularly copied by others. This is why symbols represent the outermost layer of a culture.

Heroes are persons, past or present, real or fictitious, who possess characteristics that are highly prized in a culture. They also serve as models for behavior.

Rituals are collective activities, sometimes superfluous in reaching desired objectives, but are considered as socially essential. They are therefore carried out most of the times for their own sake (ways of greetings, paying respect to others, religious and social ceremonies, etc.).

The core of a culture is formed by values. They are broad tendencies for preferences of a certain state of affairs to others (good-evil, right-wrong, natural- unnatural). Many values remain unconscious to those who hold them. Therefore they often cannot be discussed, nor they can be directly observed by others. Values can only be inferred from the way people act under different circumstances.

Symbols, heroes, and rituals are the tangible or visual aspects of the practices of a culture. The true cultural meaning of the practices is intangible; this is revealed only when the practices are interpreted by the insiders.

The ‘human habitat’ encompasses all those material remains that our ancestors have left in the landscapes of town and countryside. It covers the whole spectrum of human creations from the largest towns, cathedrals, industrial markers or highways – to the very smallest – signposts, standing stones or buried flint tools.

These are all components of the `sense of place’, through which we relate to and value our local environment. A full appreciation of the historic dimension can therefore be of the greatest importance to the development of appropriate and successful schemes of economic development and community regeneration, rather than the impediment that is sometimes supposed.

In seeking a reason for conserving cultural heritage in the form of sites and artifacts, human evolution has to be seen in the context of the current state of development of the universe. This is to be seen as a cosmos, possessing meaning and value as an ordered whole, which is reflected in the earth’s eco-system which includes the human habitat.

Modernity has led to a loss of such a holistic understanding (as existed previously, for example, in the 19th century ‘Great Chain of Being’). Matters of meaning and value have been expunged from nature, which has been reduced to simple mechanism. Can this materialistic determinism, in its ‘cosmic pessimism’, provide an ethical basis for an holistic heritage protection policy which encompasses both ecosystems and human history?

Some scientific ‘pessimists’ have argued for such a policy on fundamentally anthropocentric grounds, of purely human need and potential – which can equally justify continued exploitation/ manipulation of nature destroying ecosystems and cultural heritage. A number, notably in defending biodiversity, have stressed the preciousness of life more generally; but even this ‘preciousness’ depends finally on what Homo sapiens in its cultural achievements, has brought to what it has created.

A dualistic view of nature, as serving or subordinate to humanity and without an intrinsic value, will eventually prove ecologically unsatisfactory. Instead, nature’s worth needs to be seen in its inherent beauty, referring to an objective aspect of the universe, namely the ‘ordering of novelty’ or ‘harmony of diversity’ or ‘unifying of complexity’. These features point to a dynamic balance in beauty, too much ‘order’ leading to a banal even ‘dead’ homogeneity and too much ‘novelty’ to a breakdown of coherence, even to chaos.

This vision is best captured by the idea of ‘process humanism’ in which the cosmos is not a static condition. Creation is an ongoing, open process, in which human creativity enhances the aesthetic intensity of the universe, or can disturb the balance between order and novelty/diversity.

Humanity can only too readily be seen as ‘in charge’ and unconstrained in its immediate material, ‘worldly’ inclinations and (hubristic) ambitions. Beauty is then demoted as a significant or practical consideration. Ecological degradation is the outcome of this tendency’s ascendancy in world politics and economics. Humanity’s capabilities require it to assume its responsibilities in sustaining the cosmic process, recognizing that it is not just for humans (it can exist, already has, without them) or valueless apart from them. Global order can no longer ignore its long-run ecological, cosmic basis. To take this successfully on board, a more than techno-scientific and economic rationality is called for. Conservation is then a human responsibility to sustain and enhance the ordering of novelty and the unification of complexity as the essence of the cosmic adventure towards ever more beauty. In this context, beauty is the objective patterning of things that gives them their actuality and definiteness as intrinsic cosmic values.

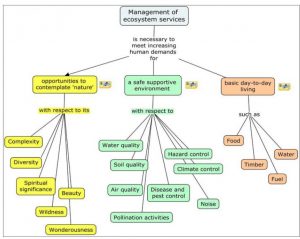

10 Managing Ecosystem Services

The aim is to create an international educational framework for comparing how different countries are managing ecosystem services. The framework will be wiki and html pages integrated with the commonly used Green Map System, C Map Tools , Articulate Presenter and e-book software to create resources for on line learning using case histories of conservation/resilience management under the conceptual banner of ‘cultural ecology’ to provide a thematic unity.

All the habitats to which we now ascribe nature conservation value and which prompt our concern to sustain them are the incidental results of long social occupacy during which there has been a dynamic interaction between culture and ecology. Now, unless checked, these random forces, which have framed the human ecological niche will mpoverish habitats and extinguish species. Conservation management is a necessary human behaviour in household. neighbourhood, region and planet for as long as the human population is measured in hundreds of millions.

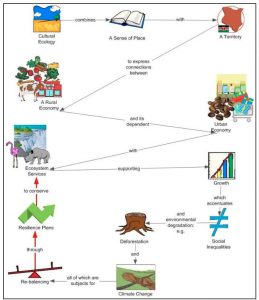

Cultural ecology as a system expressed as landscapes (Fig 1):-

-combines a sense of place (defined by historical rights and habits) with a territory (a geographical entity)

-to express connections between a rural economy (based on local production and marketing) and its dependent urban economy (dependent on distant production processes),

– with ecosystem services (the processes by which the environment produces resources utlilised by humans such as clean air, water, food and materials) supporting growth (as wealth and population size),

-which accentuates

social inequalities (the existence of unequal opportunities and rewards for different social positions or statuses within a group or society) and environmental degradation (the deterioration of the environment through depletion of resources such as air, water and soil;

the destruction of ecosystems and the extinction of wildlife) eg deforestation (the process whereby natural forests are cleared through logging and/or burning, either to use the timber or to replace the area for alternative uses.);

and climate related issues (many detrimental effects such as more frequent and severe natural disasters, droughts and floods, a rising sea level, and a reduction in biodiversity that particularly affects species upon which the world’s poor rely for their livelihoods reduce the ability of the environment to provide food, water and shelter for the people who currently live there.

As a result, many people will be forced to relocate, which requires behaviour change to re-balance people with resources. The challenge is to find the right balance between what we demand, what the environment needs, and what other people need from us in terms of food imports and exports) through resilience plans (the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change, so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure and feedbacks to conserve ecosystem services.

These connections are presented as a process diagram in Fig 1.

Fig 1 Process diagram of cultural ecology

http://archive.defra.gov.uk/environment/economy/documents/sustainable-life-framework.pdf

Fig 2 Managing ecosystem services: a concept map

This blog has been abstracted from a much larger document which is under construction at;

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1M_ZCMzqGlY-dECf5WxSFtnJFZBX0S00XJwLAA6wT1yY/edit?usp=sharing

Access the full range of educational resources at:-International Classrooms On LIne