1 Learning from the ‘primitive

The idea of the primitive human being , and the attempt at recovering the primitive mind as a kind of corrective to modernity, is evident in much of narrative fiction, where it similarly links with the themes of restlessness, alienation and exile. Indeed, travel writing and narrative fiction may be seen to feed into each other in significant ways

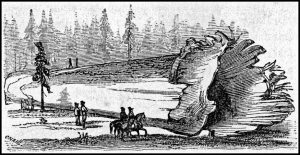

Recovering the primitive and the glorification of the un urbanised noble savage is a dominant theme in the Romantic writings of the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. For example, he wrote on the corrupting influence of traditional urban education illustrated with descriptions of nature and man’s natural response to it. The concept of the noble savage, however, can be traced to ancient Greeks who idealized the Arcadians and other primitive groups, both real and imagined. Later Roman writers gave comparable treatment to the Scythians. From the 15th to the 19th centuries, the noble savage figured prominently in popular travel accounts and appeared occasionally in English plays such as John Dryden’s Conquest of Granada (1672), in which the term noble savage was first used as an icon for the lost wisdom residing in wilderness and the cultures existing cheek and jowl with wildlands.

The importance of this kind of knowledge for a planet in crisis was the theme for the 8th World Wilderness Congress in Alaska in 2005’ Wilderness, Wildlands and People: A Partnership for the Planet At the congress, a questionnaire was distributed asking participants which writer(s) influenced them the most. There were 100 writers listed on the survey, and participants added several other names. Participants identified 91 writers, with most people mentioning several writers who have had great influence on them. Five of these writers were honoured at the congress. Sixteen others received numerous votes for their influence on attendees. These writers are Wendell Berry, Annie Dillard, Loren Eisley, Aldo Leopold, Barry Lopez, Peter Matthiessen, John McPhee, Margaret Murie, Roderick Nash, Sigurd Olson, Roger Tory Peterson, David Quammen, Gary Snyder, Wallace Stegner, Terry Tempest Williams, and Laurens van der Post. Explorers and writers, such as van der Post and Thesiger, often wrote of the ancient link between humanity and nature, and how within our fast moving cultures of today, much of this link to the inner ecologist has been forgotten.

The serious traveller seeks now, not to discover what remains unknown, but to record what is fast disappearing. Accounts of these journeys are characterised by nostalgia for ‘primitive’ modes of life that were being eroded by the inexorable advance of modernity. This nostalgia is evident in such texts as Graham Greene’s ‘Journey Without Maps’ (2002), based on a journey undertaken to Liberia in 1936, and Wilfred Thesiger’s ‘The Danakil Diaries’ (1998), based on journeys undertaken between 1930 and 1934, and it constitutes the focus of van der Post’s ‘The Lost World of the Kalahari’, based on a journey undertaken in 1955. The travellers portrayed in these works seek out remote locations and present the cultures they encounter as instances of a kind of pure primitivism threatened by the contamination of modernity and its accompanying administrations and technologies.

2 Laurens van der Post: his own invention

In an age of rampant materialism, Laurens van der Post was a passionate and prominent champion of spiritual values. He made up stories of an almost vanished Africa; a world of myth and magic in which the indigenous peoples of the continent lived for uncountable centuries before the Europeans came to shatter it. The nature of his spirituality was not always clear, and his more Messianic pronouncements could seem both portentous and imprecise, but the views he expressed in more than two dozen books struck a chord with millions of readers. His perception of life’s mysterious power began with the Bushman, the first people of his native Africa, and grew . “Men had lost their capacity to dream …” he reflected after the second world war. “I knew that somehow the world had to be set dreaming again.” For van der Post, the Bushmen were gatekeepers to the unconscious: “I sought to understand imaginatively the primitive in ourselves, and in this search the Bushman has always been for me a kind of frontier guide.”

He invented fictitious stories about his own life to carry and develop his spiritual beliefs and make them more acceptable to westerners seeking a unity with nature. This is in itself a sad reflection on how westerners rank the words of a colonel in a crack regiment, which he said he was, higher than those of an acting captain in the military police, which was the reality. The literal truth was never of much interest to van der Post because he preferred what he described as the truth of the imagination. In other words he lived his dreams. This sparked his creativity to produce stories of his heartfelt beliefs about the ills that come from racism and humanity’s severance from nature. His fertile imagination was allowed to invade his private life, too, and created a false fabrication of his personal career.

The important question is why an Afrikaner brought up in a Calvinist culture should feel so tempted by the freedom of fantasy to deliver so important a philosophical message? . Evidently the inclination was there from his youth when, isolated in a small community and inspired by his father’s excellent European library, he dreamed of a quest for the Grail, of Odysseus, of the Knights of the Round Table. Disposed from childhood to embroider and invent, he discovered that, thanks to his charm and eloquence, he could convince people. So untruth and selective amnesia became the pattern of his life. Occasionally, he admitted this. In one of his last books, ‘A Walk With A White Bushman’, he writes :

“This is one of the problems for me: stories in a way are more completely real to me than life in the here and now. A really true story has transcendent reality for me which is greater than the reality of life. It incorporates life but it goes beyond it.”

The woman who looked after him for the last four years of his life, housekeeper Janet Campbell, later said: “He was such an astonishing liar it seemed as automatic and necessary to him as breathing, from some flim-flam to do with socks to the engorged fabrication of his deeds. Consequently I found it impossible to see him as anything but his own invention.”

However, the relevant question is not so much whether van der Post’s representation of the human need to value wilderness and wildness is true, but what the context, nature and purpose are of his representation. In his essay, “Wilderness – A Way of Truth,” he recalls a conversation, possibly fictitious, he had with Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychotherapist who founded analytical psychology. According to Van der Post, Jung said “the truth needs scientific expression; it needs religious expression and artistic expression,”. Thus he sets up the need for having different, complementary attitudes and perspectives on nature.

To illustrate this, van der Post tells a marvelous tale, supposedly from the South African Bushmen, of “The Great White Bird of Truth.’ This story recounts how the community’s best hunter one day caught a glimpse in a rippling pool of a beautiful white bird flying in the sky. “From that moment on, he wasn’t the same. He lost all interest in hunting…One day he said to his people, ‘I am sorry; I am going to find this bird whose reflection I saw. I have got to find it,’ and he said good-bye and vanished,”. He travelled throughout all of Africa until at the end of his strength, watching the beautiful African sunset, he thought, “I shall never see this white bird whose reflection is all I know.” And he prepared himself to lie down and die. Then at that moment, a voice inside him said, ‘Look!’ He looked up and, in the dying light of the African sunset, he saw a white feather floating down from the mountain top. He held out his hand and the feather came into it, and grasping the feather, he died. Van der Post interprets this story as the tale of a person who is spiritually aware, is open to perceiving even a reflection of the truth, and is content with just one feather of the truth. This harkens back to the second part of Jung’s comments on the truth needing scientific, religious and artistic expression, “even then…you only express part of it,”. Van der Post stresses the ongoing need of adaptation and re-orientation of each generation to the truth of inner and outer selfhood. For him truth was the feature of his inner life.

Van der Post’s essay, “Appointment with a Rhinoceros,” is well worth the read. Briefly it is his telling of a transformative encounter with nature in his homeland of South Africa after having been away from home for 10 years, including 3 years in a Japanese concentration camp. He says that his loss of connection with his “natural self” and regaining it in a sudden communing with nature, is an “illustration of one of the many paths we can travel in order to rediscover this lost self,”. It is a really marvellous essay about the healing of war trauma through nature as well as re-establishing the harmony of inner and outer consciousness.

Luckily, the Van der Posts inner truths have been gathered together in a ‘reader’, Feather Fall, edited by Jean-Marc Pottiez They are thematically organised to reflect the patterns which have influenced his life and his writing. They distil the essence of the writer, thinker, spiritual guru and man of action.

3 Thinking with wood.

Forests lie somewhere in the widespread desire for a spiritual dimension to western life. In this connection, forests are multipurpose places of recreation and respite, deep reflection and enchantment. They are time-woven tapestries of layered histories, myths and legends. Witness to bygone gatherings and happenings; home to an abundance of wildlife. They have provided materials and inspiration for artists and craftspeople throughout the ages. There is something truly magical about being in a forest. From the moment you leave urbanity behind and step inside the leafy canopy, time and space become elastic. You enter another world of secret lives. There are hidden histories and new perspectives. The apparent stillness evaporates into a teasing multidimensional cacophony of birdsong, insects and fluttering foliage: then before your very eyes the almost suffocating chaos of branches and stems reorders itself into an awe inspiring and highly organised web of life.

As we let go of the supermarket economy we become more aware of an inner dimension in life far longer and more significant than the outer eventfulness of everyday living. We become surrounded by the universal imagery of dreams, the fertile legends and stories of ancient civilization, the intuitive teaching of prophets, poets and other pioneers of human environmental awareness. By letting ourselves think with wood rather than seeing individual trees, we are able to explore the potential in humanity to acquire self-knowledge and to live life according to its fundamental precepts. We become adventurous pioneers exploring not just the outward aspects of a turbulent and troubled world but, at a deeper level, the patterns and paradoxes of human life, the myths and dreams of the human mind, the values and cultures of different peoples, the elusive springs of ourselves. Nowhere are these creative springs more clearly evident than in the of stone spheres of Costa Rica, made in preColumbian times made by the indigenous forest peoples. The stones were originally located across the Diquis Delta and on the Isla del Caño in Costa Rica. They were uncovered during the 1930’s when the United Fruit Company started searching for new areas to cultivate their banana trees. It’s estimated that there were around 300 petrospheres that varied in size from a few centimetres to over two metres in diameter. Many of these have subsequently been relocated. The largest petrospheres weigh around 15 tons and are classed as megaliths in their own right. Most of the stone spheres are made from a hard igneous rock known as granodiorite (Gabbro) although some have been shaped from both sandstone and limestone. They were placed in geometrical positions but very few now remain in their original locations. Most have been moved to private estates, museums and government buildings. Nobody really knows why they were made and, more importantly, how they were made, but we can say that they were created as the outcome of deep spiritual thinking within a relatively small isolated community.

From the beginning, Laurens van der Post was aware of this deeper dimension in life. He never lost his sense of the overriding purpose and awesome continuity of life and the ultimate wisdom lodged in its keeping. His perception of life’s mysterious power began with the Bushmen of his native Africa. These people may be seen as an archetype of humanity revealing how primitive consciousness has become the modern unconscious. Traditional practices are not always better than their latest developments. The social institutions and technology of traditional societies are a product of the environmental conditions in which those societies evolved. They may or may not be appropriate for modern circumstances. What is new is the challenge for modern society to perceive and interact with ecosystems in ways that not only serve our materialistic and spiritual needs but also do so on a sustainable basis. Laurens van der Post sets the spiritual losses of urbanisation against the loss of wonderment in the workings of the ‘first pattern’ of things in the natural world. Nowhere is this better exemplified than in ecosystem services.

“They started at once unloading the game, and went straight on to skinning and cutting up the animals with skill and dispatch. I watched them, absorbed in the grace of their movements. They worked with extraordinary reverence for the carcasses at their feet. There was no waste to mock the dead or start a conscience over the kill. The meat was neatly sorted out for specific uses and placed in separate piles on the skin of each animal. All the time the women stood around and watched. They greeted the unloading of each arrival with an outburst of praise, the ostrich receiving the greatest of all, and kept up a wonderful murmur of thanksgiving which swelled at moments in their emotion to break on a firm phrase of a song of sheer deliverance. How cold, inhuman, and barbarous a civilized butcher’s shop appeared in comparison!”

The Heart of the Hunter, Chapter 2

“Yet with all this hunting, snaring and trapping the Bushman’s relationship with the animals and birds of Africa was never merely one of hunter and hunted; his knowledge of the plants, trees and insects of the land never just the knowledge of a consumer of food. On the contrary, he knew the animal and vegetable life, the rocks and the stones of Africa as they have never been known since. Today we tend to know statistically and in the abstract. We classify, catalogue and sub-divide the flame-like variety of animal and plant according to species, subspecies, physical property and use. But in the Bushman’s knowing, no matter how practical, there was a dimension that I miss in the life of my own time. He knew these things in the full context and commitment of his life. Like them, he was utterly committed to Africa. He and his needs were committed to the nature of Africa and the swing of its wide seasons as a fish to the sea. He and they all participated so deeply of one another’s being that the experience could almost be called mystical. For instance, he seemed to know what it actually felt like to be an elephant, a lion, an antelope, a steenbok, a lizard, a striped mouse, mantis, baobab tree, yellow-crested cobra or starry-eyed amaryllis, to mention only a few of the brilliant multitudes through which he so nimbly moved. Even as a child it seemed to me that his world was one without secrets between one form of being and another. As I tried to form a picture of what he was really like it came to me that he was back in the moment which our European fairytale books described as the time when birds, beasts, plants, trees and men shared a common tongue, and the whole world, night and day, resounded like the surf of a coral sea with universal conversation”.

The Lost World of the Kalahari, Chapter 1

Thinking with wood with a mind tuned to these writings of Laurens van der Post grasps a great mystery which will never be solved. No amount of knowledge diminishes the amount of the unknown because knowledge moves and searches for meaning. If this proposition is not accepted our consciousness is deprived of a vital proportion of reality and we become excessive and arrogant in our claims on the planet. That wood should be the basis of human civilisation is a great wonder. A sense of wonderment is part of our wholeness and keeps us humble as just another creature that has evolved on Earth and we are utterly dependent on its ecological bounty.

4 Thinking with pebbles

Laurens van der Post expressed his thoughts in the form of word pictures. Painting a picture with words through descriptive writing takes practice. Sense words, descriptive words, and plays on words are all tools that bring the writing to life. With such ‘pictures’, a writer will ensure that the reader won’t soon forget what has been written thanks to the mental landscape that is created by the author’s descriptive skills. Laurens van der Post had this power at his fingertips and could project it with confidence in talks and conversation. Already an accomplished word painter, in 1983 he published his 22nd book ‘Yet Being Someone Other’, written in an old fisherman’s watch tower on the shingle beach of the English coastal town of Aldeburgh. Many regard it as his most revealing book. It is a distillation of the thoughts that have moved him at the deepest level of imagination. This is testified by the unanimous praise heaped upon it by a wide range of influential reviewers.

The story starts with his childhood in southern Africa, and the passionate interest in ships and the sea that led him to take part, as a young man, in two voyages of special significance: the first in a whaling ship, with a Norwegian captain whose values and imaginative range unexpectedly nourished his own, and then a long voyage to Japan that not only enriched but enlarged his life. Both are absorbing tales of action and adventure; but more than that, they are narratives of personal discovery that go beyond the storms and happenings of the outside world into the uncharted waters of the other world within.

The harmonious mental blend of the external and the internal expresses the paradoxical duality of our being. The duality is brought out vividly in the author’s marvellous evocation of Japan as it was just two generations after the country was opened to the West.

With his deep-rooted sense of the sea, and of the part it has played in man’s aspirations and destiny, Laurens van der Post ends his story where it began, at the Cape of Good Hope, lamenting the loss of a line of ships whose tradition dates back to the dramatic discoveries of the Renaissance mariners. A the same time he recognizes a new dimension of hope for the questing spirit of mankind in the constant search for meaning and purpose in life. ‘Yet Being Someone Other’ brings together his veneration for the human bond with nature, his quest for the secret springs of life’s meaning, his high hopes that the family of man will heal its wounds and rediscover its soul on the way to the stars, and his conviction that he has a personal obligation to history to command the utmost respect for the bond between people and land.

‘Yet Being Someone Other’ is undoubtedly the most unusual and unplaceable of all van der Post’s writings. Like most of them it is heavily autobiographical; but, it is also much more than that — a kind of prolonged meditation on the part played in his life and that of the post-Renaissance modern world by ships and the sea. However this voyage is an interior one, seeking to understand his own selfhood and the place of humanity in the cosmos. It deals not only with the wonders of the deep but of the mysteries of the Deeps.

Regarding the identity of van der Post’s ‘other’, we must start with a quotation from Jung, van der Post’s mentor.

“Spirit is the inside of things and matter is their visible outer aspect”

(C.G. Jung, in Sabini, 2005, p. 2).

Jerome Bernstein in his book, ‘Living in the Borderland’, addresses the evolution of Western consciousness and describes the emergence of the ‘Borderland,’ a spectrum of reality that is beyond the rational yet is palpable to an increasing number of individuals. Building on Jungian theory, Bernstein argues that a greater openness to trans rational reality experienced by Borderland personalities allows new possibilities for understanding. Mary-Jayne Rust, writing about the psychological responses to ecological crises validates that language helps reconnect self with body and land. She muses on the potential of creating a language incorporating self and earth as do many languages in indigenous cultures that weave together body and land, community, and universe. In this context, it is important to inquire why van der Post, with a mind filled with knowledge about the richness of relationships between culture and environment in Africa and the Far East, gravitated to the small English seaside town of Aldeburgh and what part it played in releasing this complex literary work.

First, Aldeburgh enters the English literary landscape through the poetry of George Crabbe. In his lifetime (1754-1832), he enjoyed both critical and popular acclaim. Byron ranked him with Coleridge as “the first of these times in point of power and genius”. Samuel Johnson, Walter Scott, Edmund Burke, Jane Austen and Tennyson were also admirers. Crabbe’s best known works are the long narrative poems, ‘The Village’, published in 1783 and ‘The Borough’ in 1810. Crabbe doesn’t name the seaside town featured in ‘The Borough’, but no one doubts it’s based on Aldeburgh, where he was born and spent his early life. Some of the descriptions still apply to the place today – houses “where hang at open doors the net and cork”, marshland with “samphire banks and saltwort”, tarry boats and rounded flints. Through elegant rhyming couplets, Crabbe depicts a shocking world of poverty and brutality relieved only by the beauties of the natural world.

Second, the composer Benjamin Britten discovered Crabbe’s poetry whilst living in America. The poetry was a revelation: “I suddenly realised where I belonged and what I lacked.”. The experience evoked a longing for the spiritual overtones of that grim and exciting seacoast around Aldeburgh. On his return from the US he wrote the music for the opera Peter Grimes based on a single chapter of Crabbe’s poem and it had its first performance in 1945.. Britten made his home in Aldeburgh and three years later he founded the Aldeburgh festival. Peter Grimes in Crabbe’s poem represents the ‘other’ in the East Anglian fishing community that persecutes him as an outsider. In this context Britten is probably the most celebrated composer of oppressed ‘others’ who are misunderstood. Laurens van der Post could well be put into the category of a mystic whose message is difficult to understand.

Third, Aldeburgh remains an artistic and literary community with an annual Poetry Festival and several food festivals as well as other cultural events. Third, Aldeburgh is a tourist destination with visitors attracted by the absence of fairground entertainments and the exceptional quality of the natural wildness of its surroundings. Second homes make up roughly a third of the town’s residential property.

Finally, Aldeburgh and its pebble beach is a borderland that faces full on to the powerful eroding action of the North Sea. Its storm beach, thrown up and maintained as a dynamic linear feature of graded shingle by the tides, is a maritime wonder, an ecological wilderness of pebbles which extends for miles to the north and south of the town.

Cut off by extensive moorland, mudflats and saltmarshes to the west, Aldeburgh has always been a small self contained inward looking cultural island,with big skies over land and sea. In fact there are few places better within two hours of London for an urbanite, which van der Post was at that time, wishing to meditate on the the mysteries and tragedies of the Deeps. From his writing perch high above Aldeburgh’s shifting pebbles, which have been gradually encroaching on the town since its first settlement in Tudor times, van der Post’s gaze would be inevitably directed into the featureless, untamable grey North Sea. This was his horizon for musing on a rich segment of his inner world and its achievements.

“Accordingly I look back on countless moments like those without regret or even nostalgia, but only with unqualified gratitude to life for giving me so privileged a chance of communion with the sea and its meaning, both in the dimension of the here and now of daily life as in the depths of the spirit where, through the symbolism of the external world made manifest, we are in touch with all that has been and all that is to come”.

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 2

“Both sea and ships are in themselves natural symbols of royal and ancient standing in the mind of man”.

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 6

“Those who persevered to the true end, whatever their call to the sea, would find it had the power, unequalled by any other natural phenomenon, to transcend all and make mere man more than himself”.

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 6

A storm beach is a beach affected by particularly fierce waves usually with a very long fetch. The resultant landform is often a very steep accumulation of rock fragments composed of rounded cobbles, shingle and occasionally sand. It is one of the few wild ecosystems that has persisted visually worldwide from the ocean’s beginnings. The tidal fetch hitting Aldeburgh in a north easterly gale can be around 2000 km. Shipwreck and deaths at sea have always been talking points in the town’s daily life.

Day by day each tide animates an imperceptible progression of pebbles along by the promenade then south beyond the town to augment the great pebble bank of Orford Ness. This is the treeless, botanically sparse, marine desert, albeit only a mile across, which chimes with the Kalahari in a mind a mind dwelling on human survival. The last of the pastoralists recorded on Orford Ness, Phineas Munnings, had died long before van der Posts arrival. We can surmise that it was probably the absence of an aboriginal inhabitant to represent the ‘bushman’ of the shingle banks and marshes that prevented van der Post from articulating a particular inner response to Aldeburgh’s maritime wilderness. Nevertheless,we can imagine him treading the shingle, brooding on the fate of planet Earth and the inability of humankind to take the necessary action to bring its demands for ever more planetary resources in line with the planet’s ecological productivity.

“I myself, in my own small way in south-east Asia and all over Africa, had tried in vain to achieve a more merciful settlement of our debt to life. I had tried for some fifty years through my writing to prevent petrification and judgement according to the letter of archaic law in a court of fate whose appointed officers were executioners without love, and disaster without human bonds. How could men still doubt that disaster and suffering were the terrible physicians summoned by life when all other more gentle means of healing them had failed?”

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 7

“There seemed to me moments in a desperate time when one had also to do and act on the ordinary everyday human scene. Art and writing, it seemed, ultimately demanded not only expression in their own idiom but also translation into behaviour and action on the part of their begetters. Being and doing, doing and being, for me were profoundly interdependent, particularly in a world where increasingly it seemed to me the ‘doers’ did not think and the thinkers did not ‘do’ . . . In the Western world to which I belonged, all the stress was on the ‘doing’ without awareness of the importance to it of the ‘being’. Somewhere in this over-balance of contemporary spirit, there appeared to be an increasing loss of meaning through the growing failure to realize how ‘being’ was in itself primal action, and that at the core of ‘being’ was a dynamic element of ‘becoming’ which gave life its quality and from which it derived its values and overall sense of direction. Because of a lack of such `being’, we were constantly in danger of becoming too busy to live”.

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 6

“I believe that my own life established some small but undeniable and empirical facts: namely that every life is extraordinary; that the `average man’ is a statistical abstraction and does not exist; and that every single one of us — not excluding the disabled, maimed, blind, deaf, dumb and the bearers of unbearable suffering — matters to a Creation that has barely begun.”

Yet Being Someone Other, Chapter 7

This leaves us to question the enigmatic title of his Aldeburgh book, ‘Yet Being Someone Other’. Normally this phrase would be the start of an explanation to qualify a personal course of action. One such significant far reaching action was his departure from the Cape of Good Hope in one of the last ocean going passenger vessels. At this point of severance from his African roots van der Post presents us with an image as it would be seen in a newsreel. Yet, having an imaginative self within brought to the surface, by another root, the cultural impact of lost Portuguese explorers probing the African coastline in the days of sail for material wealth and to satisfy the insatiable human wanderlust.

Shipwreck, almost unendurable hardship at sea, and the constant and mysterious disappearance of vessels became so normal a part of Portuguese experience that it inspired a special literature of its own. Ordinary Portuguese men and women had their imagination so inflamed by what was increasingly a national horror story that they acquired an insatiable appetite, not just for factual records of what happened at sea but for fiction about the sea, ships and the men who sailed in them. It was called Literatura de Cordel, loosely translated as `string literature.’ It was given this name because so many stories of this kind came from the pens of popular Portuguese writers that they were rushed into print in a glorified pamphlet form and displayed all over Lisbon, strung up on string and hung up outside shops like some new sort of salami of the imagination, pre-cut for instant consumption.

Yet Being Someone Other, pp.22-23

Above all, van der Post’s message for the world in ‘Yet Being Someone Other’ is that there is a bushman archetype in everybody but we have lost contact with that side of ourselves and we must learn again about a universal primeval inner self that animated the ancient hunters and pastoralists. The Bushman is walking about in our midst. personifying an aspect of humanity which we all have, but with which we have increasingly lost contact. According to van der Post, Jung believed that every human being has a 2 million year-old man within himself and if he loses contact with that 2 million year-old self he loses his real roots in human evolution. This disjunction between origins and actions has impoverished us and endangered Earth itself. Diagnosing this ill revealed to van der Post that the difference between this naked little man in the desert, who owned nothing, and us, was that he is and we have, but no longer are. We have exchanged having for being. In this sense the inner bushman is presented as a bridge between the world in the beginning, with which we’ve lost touch, and the global world of consumerism, in which everyone is clamouring to satisfy wants rather than needs. The prescription is simple. Everyone must take the minimum for needs with a little bit extra to buy time for creativity. Applying the prescription is difficult because those who have gained the most from globalising capitalism will not give up their surplus to those who have the least. To this misfit between sustainability and exploitation Laurens van der Post has no answer, but then neither has anyone else.

The traveller and author Jan Morris sums up Laurens van der Post as follows:

“He is a mystic, disguised as a novelist and man of action, and he is here in the world to ponder its incalculables, and allow us to share his conjectures. Yet he seems dissatisfied with the role, and wishes always to translate his long ecstasy into something more positive, some plan of action, some practical purpose. It is as though a sense of guilt, inherited perhaps from the Calvinist conscience, drives this inspired dreamer into a closer involvement with the world’s reality: as though the dream, and the vision, is not reality enough”.

5 A wonderment curriculum

Laurens van der Post spent his life teaching us about the mismatch between humankind’s wants and needs. Since his death it is now commonplace to see that in the long run we have no choice but move towards a society in which there cannot be any economic growth, market forces cannot be allowed to determine our fate, there must be mostly small and highly self-sufficient and self-governing settlements, mostly local economies, very little international trade, highly participatory political systems, and above all a willing acceptance of frugal lifestyles and non-material sources for life satisfaction.The best that education for sustainability can achieve within present socioeconomics is to inculcate a sense of wonderment in the natural world and teach the skills necessary to provide technical fixes to overcome inevitable future catastrophe.

Regarding educating for a sense of wonderment. Albert Einstein set out the thinking framework as follows:

“I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without use of signs (words) and beyond that to a considerable degree unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that we sometimes “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts already sufficiently fixed within us. Whenever such a conflict is experienced sharply and intensely it reacts back upon our world of thought in a decisive way. The development of this world of thought is in a certain sense a continuous flight from wonder”

“A wonder of this kind I experienced as a child of four or five years when my father showed me a compass. That this needle behaved in such a determined way did not at all fit in the kind of occurrences that could find a place in the unconscious world of concepts (efficacy produced by direct “touch”). I can still remember — or at least believe I can remember — that this experience made a deep and lasting impression upon me. Something deeply hidden had to be behind things”

Rachel Carson put it this way:

“A child’s world is fresh and new and beautiful, full or wonder and excitement. It is our misfortune that for most of us that clear-eyed vision, that true instinct for what is beautiful and awe-inspiring, is dimmed and even lost before we reach adulthood. If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength”.

The conventional educational belief is that by exposing people to the outdoors and immersing them in the workings of nature will elicit a deep sense of appreciation and wonderment. Van der Posts standpoint is that It is only by finding our place in nature, and nature’s place within us, that we can truly address the environmental challenges we face today. The mission is to reconnect us to the natural world and to bring to our attention its role in sustaining human life on this planet. He sees us all as walking artists, hunter/ gatherers of stories about, place, memories and objects. His writings are a wake up call to the ecologist within us all. The educational home for this awakening is deep ecology, the environmental movement and philosophy which regards human life as just one of many equal components of a global ecosystem.

Taking this into account, the following core beliefs of a wonderment curriculum operate within the positive cycle of learning fuelled by curiosity and wonderment.

- From birth, our innate curiosity drives us to wonder, explore, dream and discover.

- Curiosity drives passion. “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious”. Albert Einstein

- Promoting belonging and inclusion for all children to ignite and follow their passionate curiosity.

- Education and learning should be a vehicle that ignites a child’s natural wonderment and curiosity encouraging them to ask why and why not.

Van der Post followed this prescription in words, developing his ideas in the form of an ongoing philosophical travelogue. In summary his message was “There is a way in which the collective knowledge of mankind expresses itself, for the finite individual, through mere daily living… a way in which life itself is sheer knowing”.

Wonderment triggers poetry. John Keating in ‘Dead Poets Society’ encapsulated the social value of poetry.

’ ‘We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.

So perhaps the aim of education for living sustainably is to prepare students for a world that will require them to learn continuously, to find and solve problems globally, to act with empathy so as to bring hope and equity to many and strive to live a life full of a passionate pursuit of beauty and wonderment. A wonderment curriculum is led by the belief that values other than market values must be recognized and given importance, and that Nature provides the ultimate measure by which to judge human endeavours.

A practical prescription is to live and learn pictorially in a state of profound wanderlust and wonder as da Vinci might have done. Leonardo da Vinci was a brilliant artist, scientist, engineer, mathematician, architect, inventor, writer, and even musician-the archetypal Renaissance man, but Fritjof Capra argues, he was also a profoundly modern. Not only did Leonardo invent the empirical scientific method I over a century before Galileo and Francis Bacon, but Capra’s decade-long study of Leonardo’s fabled notebooks reveal him as a picture thinker centuries before the term systems thinking was coined. He believed the key to truly understanding the world was in perceiving the connections between phenomena pictorially to reveal the larger patterns formed by those pictorial wow-factor relationships.

6 Profound wanderlust

Picture education is about exposing students to the wow-factor. This focuses learning on the theory of multiple intelligences and particularly on spatial intelligence. There is a number of distinct forms of intelligence that each individual possesses in varying degrees. Gardner proposes eight primary forms: naturalistic, linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, body-kinesthetic, intrapersonal and interpersonal. A number of others also suggest an additional one: technological.

One implication of Gardner’s theory is that learning/teaching should incorporate the intelligences of each person. For example, if an individual has strong spatial intelligence, then spatial activities and learning opportunities should be used. A wonderment curriculum has to concentrate on the principles of picture production. It is probably true to say that all people to a greater or lesser extent possess spatial intelligence. It has been estimated that visual learners comprise 65 percent of the population, so crafted images are clearly key to engaging people in eLearning courses and making picture education accessible to most learners.

People with spatial intelligence (“picture smart” or visual smart) have the ability, or preference, to think in pictures. Spatial intelligent people create and use mental images; enjoy art, such as drawings, and sculpture, use maps, charts, and diagrams; and often remember with pictures through the process of mind mapping.

The other thing that picture education is about is the feeding of wanderlust. Wanderlust is defined as the desire to gather knowledge by seeing new things and is usually applied in the context of the urge to travel. According to Miriam Websters Dictionary, the definition of Wanderlust is simply “a strong desire to travel”. It comes from the German language and is spelled Wanderlust. It is a relatively new word, dating back to the beginning of this millennium. These days the world is explored and presented through wanderlust images, when the traveller goes forth for pleasure or for political, aesthetic and social meaning.

Andrew Delaney, Director of Creative Content at Getty Images explains Wonderlust (sic.) Imagery as: “Images that inspires a sense of awe. They are images that are connecting us with our surroundings and elicit a reaction of wonder when you see them.”

Here are some of Delaney’s key points for teachers wishing to produce their own Wanderlust Imagery:

- Work with depth.

- Play with colour and texture.

- Give a sense of the unknown.

- Don’t worry about showing “bad weather”.

- Mother Nature is often the “hero” in the image.

- Be very aware of scale and effective composition.

- Catch the particles in the air to diffuse the light e. g. smoke or dust.

- Experiment with a wider crop. Embrace the 16:9 format to illustrate the scale of nature.

- Dare doing a non-extreme sports shoot. A contemplating feel is often more welcomed.

- Make pictures that are inclusive, that makes you wish you were there. Sometimes cliché works.

- You don’t always have to show the entire object to get other to understand what you are saying. Don’t be afraid of cropping.

- Use a subtle approach to colour rendering. Colour pallets are becoming more subtle. Man and nature are becoming more blended.

Delaney makes some interesting points when talking about authenticity of the image. The concept of Point of View (POV) photography can sometimes be very effective when trying to evoke a feeling with the viewer, because it is about enjoying what that person behind the camera is enjoying. He says: “Be prepared to either discover it, or create a set of circumstances where the moment happens and you are there to photograph it.” Another of his tips is to try to be present and do your best to catch the decisive moment. It is not about controlling a shoot, but creating a shooting window, where as a period of actions happens and you step out of it to record what happens,

“When the editors at Getty first look at a picture, they see if it works emotionally. Technical qualities are secondary but can sometimes add authenticity. Flare, backlight, a crooked horizon, blown highlights, or excessive grain/noise can all evoke emotions and helps with nostalgia. This must however be done delicately.”

“All pictures today live or die on the basis of how they look as a thumbnail – which means you absolutely got to get your composition right”. If your picture doesn’t read as a thumbnail, it’s going to die. It is not going to get clicked on. The client of ours is not going to go to the next step of investigating an image if it fails the test of what it looks like as a thumbnail. It’s got to look good”.

The concept of accessing a photographic point of view is central to generate the motivation to travel in order to experience the point of view first hand. Travel needs and motives reveal educational needs because they stem from an inner feeling of wanting to learn about new places and things, further fuelled by external pull factors that promise just that. This contemporary type of explorer has a fairly clear idea where she wants to go and she is not travelling away from her home (such as it is the case with escape), she is travelling toward a fixed destination. Her basic need springs from the feeling of a deficiency that she has encountered in her home environment. This deficiency (contrary to a lack) is subjective and a social construct. If the traveller’ nowadays described as a tourist, is not capable of satisfying this deficiency (with its corresponding need), she has to look for other ways to continue.

The first aim of an escape is to gain distance from one’s home environment. It is like living in between two realities: the home environment that has been left behind, and the destination where one is physically present but not as a part of it; this is a betwixt and between situation that is also referred to as liminality. The alienation of the home environment during the period of being a traveller refers to a space-related liminality, wherein places that themselves are liminal, such as beaches (between land and sea), are usually preferred. Profound changes in the way that place and time are experienced as a result of accelerated globalization have led to a new questioning of identity, the self and the place people take in this world. Not only are ways of living leading to a sense of loss of identity, for many individuals computerized work conditions and everyday roles impose constraining and monotonous routines in which individuals find it difficult to pursue their self-realization. Many theories on motivation and needs to be satisfied have used this model as a basic educational outline. Pearce applied it to the case of tourism and combined it with the tourist’s experience. He proposed five layers of holiday motivations:

- relaxation (rest <> active)

- stimulation (stronger emotions)

- social needs (family, friends)

- self esteem (self development through cultural, nature or other activities)

- self-realization (search for happiness)

Travel needs and motives follow these different levels, the first two being the most common. It should be noted that this model is based on the Western world and in those parts where community life is especially valued, the ultimate goal is often not self realization but being able to serve the group, for example.

Through the works of Laurens van der Post there runs a thread demonstrating intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence. Overall his writings are a philosophical travelogue, communicated in words. They illuminate the capacity of humanity’s inner life to distinguish the evils of modern civilisation, the life-enhancing wonders of primitive (especially Bushman) culture, and for communicating ecstatically detailed sunsets, sunrises, lions, elephants, bees, and extraordinary facts about the wilderness of (it seems) South-West Africa. His writings are short on pictures. This is a feature of the times when they were written. A large body of research indicates that visual cues help us to better retrieve and remember information. The research outcomes on visual learning make complete sense when you consider that the human brain is mainly an image processor (much of our sensory cortex is devoted to vision), not a word processor. In fact, the part of the brain used to process words is quite small in comparison to the part that processes visual images.

If we think of literacy as reading and writing words, visual literacy can be described as the ability to both interpret and create meaningful visuals. With the constant, overwhelming flow of information and communication today, both parts of this modern literacy equation are non-negotiable Our brains are wired to rapidly make sense of and remember visual input. Visualizations in the form of diagrams, charts, drawings, pictures, and a variety of other imagery can help students understand complex information. A well-designed visual image can yield a much more powerful and memorable learning experience than a mere verbal or textual description. Movies and still images have been included in learning materials for decades, but only now has faster broadband, cellular networks, and high-resolution screens made it possible for high-quality images to be a part of eLearning. Graphic interfaces made up of photos, illustrations, charts, maps, diagrams, and videos are gradually replacing text-based courses. We are now in the age of visual information where visual content plays a role in every part of life.

According to Lynell Burmark, an education consultant who writes and speaks about visual literacy:

“…unless our words, concepts, ideas are hooked onto an image, they will go in one ear, sail through the brain, and go out the other ear. Words are processed by our short-term memory where we can only retain about seven bits of information (plus or minus 2) […]. Images, on the other hand, go directly into long-term memory where they are indelibly etched.”

Because of television, advertising, and the Internet, representing social facts pictorially as resources for learning through visuals is now the primary literacy of the 21st century. It’s no longer enough to read and write text. Students must learn to process both words and pictures. They must be able to move gracefully and fluently between text and images, between literal and figurative worlds.

Today, anyone with a digital camera and a personal computer can produce and alter an image. As a result, the power of the image has been diluted by the ubiquity of images and the many populist technologies (like inexpensive cameras and picture-editing software) that give almost everyone the power to create, distort, and transmit images. But it has been strengthened by the gradual capitulation of the printed word to pictures, particularly moving pictures . The ceding of text to image has been been likened to an articulate person being rendered mute, forced to communicate via gesture and expression rather than speech. It was as a storyteller that Laurens van der Post communicated to people in their millions. Our brains are far more engaged by storytelling than a list of facts–it’s easier for us to remember stories because our brains make little distinction between an experience we are reading about and one that is actually happening. But a point can be driven home even more effectively by images.. That’s because visuals add a component to storytelling that text cannot: speed. Research shows that, visuals are processed 60,000 times faster than text, which means you can paint a picture for your audience much faster with an actual picture. It’s no surprise then that tweets with images are 94% more likely to be retweeted than tweets without. This also points the way to the use of Internet media such as Pinterest (pinboards), Tumblr (picture blogs) Instagram (social networking) and Mindomo (mindmaping) for mass education.

7 Internet References

Wiki

http://digthatpic.wikispaces.com/

Pinboards

https://www.pinterest.co.uk/zygeena/

Picture blog

https://rescuemissionplanetearth.tumblr.com/

Social media

https://www.instagram.com/rescuemissionplanetearth/

Mindmaping

https://www.mindmeister.com/346370505?t=HEIIHcPdDZ

Quotations

https://ratical.org/many_worlds/LvdP/quotations.html

Teaching nature

http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/commissioned_reports/476.pdf

Nature photography

http://www.lo-naturephoto.se/index2.html

Wonderment

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/sep/22/biography.artsandhumanitiesm

Writers and wilderness

http://www.wilderness.net/library/documents/IJWAug06_Baron.pdf

Yet Being Someone Other

http://www.eafa.org.uk/catalogue/5127

Read more at https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1044108/feather-fall/#zzYvRy57w0u426Tq.99

https://sizeofwales.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/A-fresh-look-at-Tropical-Rainforests.pdf

http://rainforestartproject.org/

https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-187844978.html

https://www.tumblr.com/search/Laurens%20van%20der%20Post

http://jeiphoto.com/what-is-wonderlust-photography/

http://www.depthinsights.com/blog/nature-has-no-outside-navigating-the-ecological-self/

https://www.quora.com/Why-do-I-feel-as-if-there-is-more-than-one-person-living-inside-of-me

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_multiple_intelligences

http://www.tourismtheories.org/?p=341

https://jpehs.co.uk/publications/being-with-grimes-the-problem-of-others-in-brittens-first-opera/

http://info.shiftelearning.com/blog/bid/350326/Studies-Confirm-the-Power-of-Visuals-in-eLearning

http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-image-culture