1 Tapping into land

Now that mining companies have begun digging up Mongolia to feed minerals to the newly emerging industrial economies of the Far East, Earth is losing its last self-sufficient pastoral expression of cultural ecology. Only one per cent of Mongolia is cultivable. For thousands of years Mongolians have relied on their free ranging cattle, horses, yaks, goats and camels. Even now, most herding households are self-sufficient in meat and milk products and earn an income from selling live animals, milk, meat, skins and hides, wool and cashmere. But increasingly Mongolians are squatting on the outskirts of their capital Ulan Bator waiting for urban jobs to be generated from the billionaire revenues expected from the Canadian mine at Oyu Tolgoi. The mine is working one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper deposits. When fully operational it will account for about one-third of Mongolia’s economic activity. But, even now as their government argues with the mining company about just shares from the enterprise, more and more people are abandoning their nomadic ways in favour of city life. The familiar problems of urbanisation have already surfaced at Ulan Bator, where shanty towns now make up half the entire city.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of miles away, in the Welsh county of Pembrokeshire, eight families have started a British suburban neo-Neolithic life on 75 acres of marginal farm land in houses built of straw. Planning permission says they have to earn three quarters of their living from the land and take care of their own needs for energy water and sewage.

It is ironic that both these social groups are orientating their lives towards betterment; the Easterners want the fruits of mass production in the city; the Westerners aim to meet their needs by adopting a land-based lifestyle. The former are hoping to slot into a global culture of consumerism. The latter have cut their ties with an urban infrastructure by growing their own food making their own electricity and milking their own cow. They are doing this whilst producing some creative craftwork on the side.

What links these two societies under change are the cultural adaptations they will have to make to connect their society with the ecological particularity of the living world. The industrialised Mongolians will maybe make this connection superficially when they buy their supermarket milk and see symbols of their former connection with the land printed on plastic cartons. The Pembrokeshire diggers will coax their milk from a living, breathing, animal, which is a highly visible herbivore in their relatively small garden food chain. Both societies are nevertheless having to face up to the same questions that were first raised a century ago in Europe at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. This was a time that also marked the beginning of secularism and the loss of a spiritual lodestone relating culture to environment in a ‘big history’. In this context, culture denotes the totality of the social environment into which a human being is born and in which he/she lives. Culture in this sense includes the community’s institutional arrangements (social, political, and economic) but also its forms of art and knowledge, the assumptions and values embedded in its practices and organization, its images of heroism and villainy, it various systems of ideas, its forms of work and recreation, its origins and destiny and so forth.

In particular, the migrating families at opposite sides of the world, who are actually activated by new cultural values, will sooner of later have to come to grips with the idea that “land” as a whole is an object of moral concern. This proposition, was first articulated by Aldo Leopold in his book ‘Sand County Almanac (1848)’

2 Ethics of land use

Leopold’s summarised his standpoint as follows:

“The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land.

This sounds simple: do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave? Yes, but just what and whom do we love? Certainly not the soil, which we are sending helter-skelter downriver. Certainly not the waters, which we assume have no function except to turn turbines, float barges, and carry off sewage. Certainly not the plants, of which we exterminate whole communities without batting an eye. Certainly not the animals, of which we have already extirpated many of the largest and most beautiful species. A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of these ‘resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state”.

Since writing this, Leopold has stimulated writers to argue for certain moral obligations toward ecological wholes, such as species, communities, and ecosystems, not just their individual constituents. From this perspective it appears that the Mongolians are moving away from this feeling of cultural wholeness with Nature, whilst the Pembrokeshire families are facing up to the vexed question of how urbanised human beings should relate to habitats, ecosystems and species in their pursuit of happiness with betterment. On past experience we can pretty well guarantee that before long some of the urbanised Mongolians will be yearning for betterment that is not connected with increased monetary riches. Could the universal goal of betterment be a world where parents place the emotional, intellectual and moral needs of their children above materialism? This was the belief of John Ruskin, writing about dehumanising Victorian urbanism twelve years after Leopold. His goal of cultural ecology was to produce children as truly ‘bright eyed and happy hearted human creatures’, who could be introduced with the words “these are my jewels”.

Ruskin also encapsulated the purpose of political economy in the following paragraph.

“There is no wealth but life. Life, including all its powers of love, of joy, and of admiration. That country is the richest which nourishes the greatest number of noble and happy human beings; that man is richest who, having perfected the functions of his own life to the utmost, has also the widest helpful influence, both personal, and by means of his possessions, over the lives of others”.

Ruskin sought a practical application of his philosophy by tapping into a two-way stream of ideas: those ideas presented with the purpose of exposing contemporary social evil and distress, and those presented in order to show a way out of the social muddle into happiness and greater security. His practical solution in the 1870s was to establish The Guild of St George, a project which he summarised as follows:

‘We will try to make some small piece of English ground, beautiful, peaceful, and fruitful. We will have no steam-engines upon it, and no railroads ; we will have no untended or unthought-of creatures on it; none wretched, but the sick ; none idle, but the dead. We will have no liberty upon it; but instant obedience to known law, and appointed persons : no equality upon it; but recognition of every betterness that we can find, and reprobation of every worseness. When we want to go anywhere, we will go there quietly and safely, not at forty miles an hour in the risk of our lives ; when we want to carry anything anywhere, we will carry it either on the backs of beasts, or on our own, or in carts, or boats ; we will have plenty of flowers and vegetables in our gardens, plenty of corn and grass in our fields, and few bricks. We will have some music and poetry; the children shall learn to dance to it and sing it; perhaps some of the old people, in time, may also’.

Juxtaposing Leopold and Ruskin defines the land ethic as being ecologically centred because it focuses on the moral relationships within the natural world, particularly between humans, the land and each other. These relationships were formulated in the context of modernism by Lynn Holtzman as an ecologically-integrated Golden Rule. The goal is to foster and maintain relational harmony and health between humans and between humans and the land, thus achieving Leopold’s ultimate goal of ‘land health’, “a state of harmony between men and land”. J. Baird Callicott has gone further into ecological detail. He believes that moral value is determined by an individual’s contribution to maintaining the whole, that is, the whole possesses the greater moral value. The land ethic, Callicott argues:

“…. not only provides moral consideration for the biotic community per se, but ethical consideration of its individual members is pre-empted by concern for the preservation of the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community”.

3 Ecological beauty and morality

Because humans are an integral part of the biotic community, individuals and societies are included in the beauty of life as it has evolved on Earth. As an example of ‘functional Beauty’, the beauty found in the human environment falls into a broad category, which includes architecture, everyday artefacts, events, and activities, and the arts. Ruskin’s conception of painting as language permits him to replace an older theory of art imitating nature, traditionally central to views of art, with the theory that painting utilizes systems of visual relationships that express the essentially inimitable tones, tints, and forms of nature. Ruskin had an acute sense of visual beauty, which he discovered and renewed lifelong in landscapes and townscapes. While he was appalled by many aspects of urban life he loved the old towns and cities of Europe. He could only account for the sense of intense pleasure he experienced in such places, which he recognised was analogous to the contemplation of natural beauty in the living world, by integrating this experience in his ideas about beauty in Nature. So, for Ruskin, art in town and country, the human ecological niche, can remind humanity of what it has lost and, to a degree, restore it in the imagination.

“Even this most basic function of art bears great gifts to man, if he will only accept them; for by recording the truths of sky, mountain, and sea, painting can bring an awareness of nature into the dark confines of an industrial age”.

Ruskin, who believes that much human strength and health of spirit comes from nature, tells his Victorian readers:

“You have cut yourselves off voluntarily, presumptuously, insolently, from the whole teaching of your Maker in His universe” (16.289)”.

For Ruskin, art is defined in the medieval sense of making things and is an effort to furnish the human ecological niche. In particular, art carries social messages as part of an evolved system of social cohesion and a reminder that in everything we do we are part of Nature. In Ruskin’s day the driver of this big history of mankind was God. Now science has pointed us towards natural selection. Nevertheless, writing in ‘The Stones of Venice’, drawing from his response of reading Wordsworth, Ruskin is still able to make us understand the distinctive and different aims of art and science. Wordsworth had said,

“The appropriate business of poetry, (which, nevertheless, if genuine, is as permanent as pure science,) her appropriate employment, her privilege and her duty, is to treat of things not as they are, but as they appear; not as they exist in themselves, but as they seem to exist to the senses, and to the passions.”.

4 Nature: aspect and essence

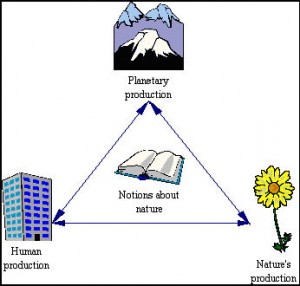

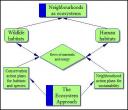

Fig 1 Aspect and essence: a cultural response to ecology

Ruskin contrasted Wordsworth’s kind of ‘poetic truth’ with the province of science (Fig 1), which was to produce an understanding of ‘impressions’, which are the ‘surface truths’ of the material world:

“Science deals exclusively with things as they are in themselves; and art exclusively with things as they affect the human sense and human soul. Her work is to portray the appearances of things, and to deepen the natural impressions which they produce upon living creatures. The work of science is to substitute facts for appearances, and demonstrations for impressions. Both, observe, are equally concerned with truth; the one with truth of aspect, the other with truth of essence. Art does not represent things falsely, but truly as they appear to mankind. Science studies the relations of things to each other: but art studies only their relations to man: and it requires of everything . . . only this, – what that thing is to the human eyes and human heart, what it has to say to men, and what it can become to them. (11.47-48)”.

“Expansive, beautiful, and blue!” This was John Ruskin’s first impression of the natural beauty of England’s Lake District in the 1830 poem “Iteriad: or, Three Weeks Among the Lakes”. It was from this observation that he began a long association with the region. In his book ‘Ruskin and the English Lakes (1901)’, Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley explored Ruskin’s connection with the English lakes, from his first visit in 1874 to his burial in the Lake District village of Coniston twenty five years later. A friend of Ruskin, Rawnsley was inspired by his teachings on the preservation of open spaces and conservation of historic properties to co-found Britain’s National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. The criteria for seeking out and protecting such places can be traced to Ruskin’s love of the materiality of nature expressed in terms of the higher spiritual truths it might offer

Art, which deals in the truths of experience, adds to the wealth of human knowledge by permitting us to see and feel with the faculties of another greater than ourselves. For this reason, truly imaginative paintings have an “infinite advantage” (5.186) over our actual presence at the scene they depict since they provide a “penetrative sight” and “kindly guidance” (5.187) that, like an imaginative lens, increases our powers of beholding nature and man.

This view of painting as a moral window on nature has come down to modern times. For instance it prompted John F Kennedy to write of the need to bring ecological awareness into political economy:

“To protect nature is to follow a moral path, but ultimately we do it not for the sake of trees and animals, but because our environment is the infrastructure of our communities. If we want to provide our children the same opportunities for dignity and enrichment as those our parents gave us, we’ve got to start by protecting the air, water, wildlife, and natural treasures that connect us to our national character. Therein lie the values that define our community and make us proud to be Americans”.

When writing this way Kennedy, like many Americans of his generation was a believer in Ruskin’s aesthetic theory, which had been adopted by American educationalists who read his works in the 1870s. They promoted his views with the moral message as being especially suited to becoming part of general education. Passages from Ruskin on “Distribution, “from ‘The Political Economy of Art’, recommended the beautification of schools and the use of pictures in the education of boys, because:

“the eye is a nobler organ than the ear; and … through the eye we must, in reality, obtain, or put into form, nearly all the useful information we are to have in this world.”

These writings were frequently quoted by American advocates of picture study. ‘Sesame and Lilies’, a pair of lectures on male and female education delivered in 1864, was especially popular in the United States. American editions were published as early as 1865 and continued to be reissued frequently through the first half of the twentieth century up to 1944. This was coupled with the availability of reproductions of famous paintings. In a period that romanticized the artistic genius, exposure to masterpieces was valued because they somehow provided contact with the larger spirit of creativity. In an era of social reform, picture study was expected to supplement moral and religious instruction, for example, bringing elite virtues to poor immigrant children.

5 Visual big history

Ruskin believed that to develop a personal conception of nature from studying a picture the viewer must adopt the most childlike suspension of disbelief: the canvas should always seem a real place to be entered, the universe should always be a system “out there”, with the picture being part of a circle whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere This is the ‘perpetual newness of infinity’ that comes from picture study. The viewer is encouraged to take an element and make a life of it. As an artefact of human social evolution a picture is therefore part of big history. Bill Gates referring to the impact on his educational experience of thinking big history described it in the following way.

‘I wish everyone could take this course. Big history literally tells the story of the universe, from the very beginning to the complex societies we have today; it shows how everything is connected to everything else [and] weaves together insights and evidence from so many disciplines into a single, understandable story – insights from astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, anthropology, history, economics, and more.”

Ruskin in ‘Modern Painters’ places himself in a big history of cultural ecology within a timeline that began with God. He describes the forces involved by relating his visual experience of a dark, still July evening in the Alps, lying beside a fountain midway between Chamouni and Les Tines.

Suddenly, there came in the direction of Dome du Gouter a crash — of prolonged thunder; and when I looked up, I saw the cloud cloven, as it were by the avalanche itself, whose white stream came bounding down the eastern slope of the mountain, like slow lightning. The vapour parted before its fall, pierced by the whirlwind of its motion; the gap widened, the dark shade melted away on either side; and, like a risen spirit casting off its garments of corruption, and flushed with eternity of life, the Aiguilles of the south broke through the black foam of the storm clouds. One by one, pyramid above pyramid, the mighty range of its companions shot off their shrouds, and took to themselves their glory — all fire — no shade — no dimness. Spire of ice — dome of snow — wedge of rock — all fire in the light of the sunset, sank into the hollows of the crags — and pierced through the prisms of the glaciers, and dwelt within them — as it does in clouds. The ponderous storm writhed and moaned beneath them, the forests wailed and waved in the evening wind, the steep river flashed and leaped along the valley; but the mighty pyramids stood calmly — in the very heart of the high heaven — a celestial city with walls of amethyst and gates of gold– filled with the light and clothed with the Peace of God. And then I learned — what till then I had not known — the real meaning of the word Beautiful. With all that I had ever seen before — there had come mingled the associations of humanity — the exertion of human power- — the action of human mind. The image of self had not been effaced in that of God . . . it was then that I understood that all which is the type of God’s attributes . . . can turn the human soul from gazing upon itself . . . and fix the spirit . . . on the types of that which is to be its food for eternity; — this and this only is in the pure and right sense of the word BEAUTIFUL .

Sixteen years before the publication of the Origin of Species, when Darwin was debating when he should publish his ideas on natural selection, Ruskin had set out to prove that ‘the truth of nature is a part of the truth of God’ (3.141), with the corollary that ‘the truths of nature are one eternal change – one infinite variety’ (3.145) – evidence that she is ‘constantly doing something beautiful for us’ (3A5FY. The broad religious argument had been elaborated with a variety of emphases over the centuries. Ruskin had been exposed intensively as a child to this theological thinking and could not adopt Darwinism. It is therefore interesting to compare his description of God’s gift to man of Earth’s artistic beauty, which glues humanity to eternal life, with Darwin’s famous conclusion to The Origin of Species. Using the example of a ‘tangled bank’, Darwin envisages the ‘Creator’s’ role as leaving Nature to its own devises where at any time the outcome is the result of a process of competition between a variety of living things.

It is interesting to contemplate a tangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent upon each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with reproduction; Inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.

These early attempts to find a holistic framework for promoting artistic endeavour as the moral link between culture and ecology actually began with Wordsworth. In his poem ‘Tintern Abbey’ (1798), he described a three stage development model of landscape responsiveness derived from his own life experience. The first stage was the child’s delight in nature as a big playground with trees to climb and fields to race around in. The second stage, in his early 20s, was the experience of nature’s colours, forms and sounds as a source of intense sensuous and aesthetic pleasure, with a sharpened sense of nature as a refuge from cities. The third stage was the loss of that sensuous delight in the natural world, which became replaced with a recognition of nature’s power to stimulate more complex moral and spiritual comfort and insight. For Aldo Leopold, reaching the third stage allowed him to recognise that a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of habitats and species to being a plain member and citizen of a global ecosystem, showing respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the ecology of all living beings. This is the best kind of transformative curriculum for the children of urbanised Mongolians and the re-ruralised Pembrokeshire diggers.

http://www.academia.edu/446498/AesthEthics_The_Art_of_Ecological_Responsibility