A will to till one’s own of soil

Is worth a kingly crown,

With bread to feed the belly need,

And wine to wash it down.

So with my neighbour I rejoice

That we are fit and free,

Content to praise with lusty voice

Bread, Wine and Liberty.

(Robert William Service)

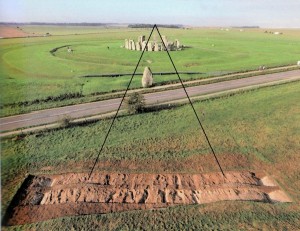

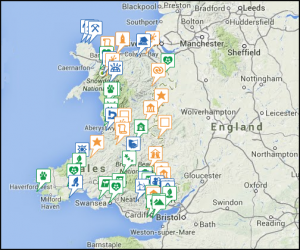

(Clee Fields; Google Map (2015):

RF= Ridge and furrow markings in school playing field; HF=Horses Fields).

1 Grass roots and neighbourhoods

The earliest origins of the use of “grass roots” as a political metaphor are obscure. In the United States, an early use was thought to have been coined by Senator Albert Jeremiah Beveridge of Indiana, who said of the Progressive Party in 1912. “This party has come from the grass roots. It has grown from the soil of people’s hard necessities”. He was referring to the party’s demand that power must reside in communities where citizens may decide on law by popular vote. This philosophy rested on the idea that the division of land and its settlement created groups of neighbours who had a common interest in maintaining the well being of their shared environment. This idea was recently pursued by the British Conservative Party in its search for policies to transfer centralised power to communities in the context of promoting local plans for sustainable development. The organisation of grass roots neighbourhood groups for local action were defined as follows:

- a new group or an existing not for dividend group within an institutional setting (e.g. scouts, residents association; social enterprise or charity);

- comprised of people living in a defined geographical area;

- have a named leader who is willing to supply their contact details and address for enquiries – required to agree to abide by a neighbourhood ethical code of conduct (to be developed through consultation). This code of conduct will protect neighbourhood groups against extremist causes;

- be required to be publicised online and through other channels, so that new potential members can enquire about joining/to be rated and/or receive feedback

The aim is give new powers and rights to groups of neighbours so that:

- Neighbourhoods will be able to bid to take over the running of community amenities, such as parks and libraries that are under threat.

- Neighbourhoods will be given a right of first refusal to buy local state-owned community assets that are for sale or facing closure. This will cover assets owned by central government and quangos, not just town halls.

- Neighbourhoods will also have a right of first refusal to take over and run vital commercially-owned community assets when they shut down – for example, those post offices, pubs and shops whose continued survival is of genuine importance to the local community.

- We will give neighbourhoods detailed street-by-street crime data, so that they can hold the police to account at local beat meetings.

- Neighbourhoods will be able to start their own school, giving them greater control over their children’s education.

- Neighbourhoods will be given the power to engage in genuine local planning through collaborative democracy – designing a local plan from the “bottom up”.

- The Sustainable Communities Act will be used to ensure that neighbourhoods have access to line-by-line information about what is being spent by each central government agency in their area, and the power to influence how that money is spent.

- Allow neighbourhoods to create Local Housing Trusts to enable villages and towns to develop the homes that local people want, with strong community backing.

- Greater access to funding for neighbourhood groups, for example the neighbourhood element of local tariffs raised from development.

- Civil servants will be defined as civic servants and promoted on their record of engagement with neighbourhood groups.

The story of the division of land to form neighbourhoods is vibrant with human problems of life, of labour and of socio-political organisation. In Britain and in Western Europe as a whole, every parish bears the marks of the comings and goings of people who, over the centuries, have added to and taken from the top few centimetres of soil upon which humanity depends to satisfy its many needs and wants. Soil is the ultimate cultural resource. Amid all the changes which have swept over rural life, traces of past modes of living remain intact, etched into the ground beneath our feet, described in writings and preserved in maps. They are a haunting memory which challenges the environmental maladjustments of urban life and draws the town dweller back to the soil from which all wealth and conflict comes. Every person who has focussed on a patch of it, through deed or mind, has a master key to the storehouse of local cultural ecology and a reason to engage in the politics of land ownership and the history of how these patches, first scratched by primitive tools, became fields in the modern mind. It is in the latter imaginative sense that most of us begin our working day in a place that once supported a farmer groping towards an understanding of his place in nature. Tillage and herding compelled him to observe non-human beings more closely. Mating and lambing, sowing and reaping, making hay, all dovetailed into questions of selfhood posed by the passing of seasons. This is the cosmopolitanism of good neighbours because neighbourhood is the property of imagination that binds people together in a common survival imperative at meeting places, each of which is a common cultural focus independent of creed and nation.

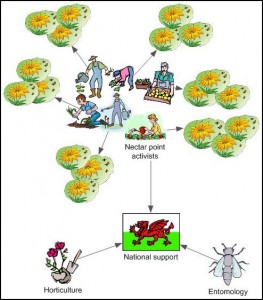

Many environmental problems can be traced back to local communities and that is why groups of neighbours have an important role to play in gathering community support to implement environmental programmes. An action plan for an old field with a hedgerow can provide a meeting place to begin a citizen’s cultural ecology network, particularly as old fields are critical wildlife habitats essential for the survival of wildlife but which can also be a place to meditate on our place in nature.

2 Symbols of remembrance

Tim Dee writes in his book ‘Four fields’ about some real fields, continents apart, growing a few hundred acres of grass that stand for our cultural appropriation of ecosystems which predate human evolution. He presents fields as found objects that make us look and think about the ways in which we have corrupted nature, yet still need to walk as good neighbours alongside wilder beings, even if we have to meet nature in an untidy patch of grass sighing in the wind.

“Without fields of my own, these chapters are my field-searches”. The field to which I return most often is currently rough grazing land at Burwell in the Cambridgeshire fens, one mile from where I live. This field was once a fen and the intention of its current owners is that it will be fen again, one day. The other three are foreign plots that I have known (in part) across some years: far afield, but not.

The first of these is in Zambia on an old colonial farm. This particular field once grew tobacco but is at present overgrown with grasses and scrub. I have already written a little about these Zambian fields. Since those first words the farmer has died (he is buried near his old crops) and I have married Claire, the woman who showed me the field, the farm and the farmer.

The second foreign field is a battlefield, and the remnant shortgrass prairie and adjacent croplands, in Montana in the USA where Sioux and Cheyenne warriors killed George Custer and his party in June 1876, in a battle which as much as anything was a fight over grass.

The last field is in the abandoned village of Vesniane in the Exclusion Zone near the exploded nuclear reactor at Chernobyl in Ukraine. Until April 1986 it was a meadow grazed by cows. When I went there, the last thing I saw was an empty aluminium milk churn lying on its side, in the open doorway of a ruined byre at the field edge.

Each of these four fields has been turned over in one way or another for as long as they have been fields – it’s in their nature. But now each is at a more angled point in its life. Fields cut from cleared scrub are abandoned back to thorns and thickets. Wild grasslands have become battlefields and then the holding place for the dead of those battles. Pasture is poisoned. A plot will be unplumbed. Territory, ownership, the exploitation of land, its meaning and value, the grass itself – all has been and is being argued over. There are tangled human voices in each field but there is also the sound of the grass”.

The first serious adult contact I made with fields was through the history of Suffolk’s coastal villages, the heartland of my mother’s family that was lost to the sea. The poet, Blake Morrison, now sees there a rapidly eroding cliff top field where ‘wheat is living on the edge‘ and there is “…. empty air where churches stood”. This poetic vision connects washed away fields in the parishes of Covehithe and Dunwich, with their present-day inhabitants and visitors, within a perspective of the deep history of cosmology and current climate change.

This theme of memory and place is taken up by Richard Irvine and Mina Gorji in their article ‘John Clare in the Anthropocene’. Here they explore what it might mean to interweave social and natural history as a remembrance of cultural ecology within deep time, taking as their inspiration the work of another English poet John Clare (1793-1864). They begin with the notion that we are now living in the Anthropocene, a geological epoch dominated by global climate change of our own making. We can say that the Anthropocene began with the intensification of agriculture in the 17th century.

This process was picked up by Clare in his poem ‘The Lament of Swordy Well’, composed in the early 1820s. Here he lets a relatively small local grassy limestone heath in eastern England, known as Swordy Well, relate the impact of the agricultural revolution on the micro-morphology of its diminutive soils and ecosystems. The creatures affected also include humans, When Swordy Well speaks as an assaulted semi-wild thing it takes on the lament of the human community of neighbours who once had the cultural freedom to harvest its bounty before it expressed a new cultural ecology when tidied into fields:

“I couldn’t keep a dust of grit Nor scarce a grain of sand

But bags and carts claimed every bit

And now they’ve got the land

I used to bring the summer life

To many a butterflye

But in oppressions iron strife

Dead tussocks bow and sigh

I’ve scarce a nook to call my own

For things that creep or flye

The beetle hiding neath a stone

Does well to hurry bye”.

Swordy Well, was a piece of common land associated with ancient rights of the villagers living around it to graze their animals. One of the first moves towards industrial agriculture was for the owners of such common land to use Parliamentary process to divide up commons into fields with hedges, ditches and fences. Paths were blocked off and the fields were measured, given names, then sold or rented privately. Local residents lost their ancient right to freely graze their livestock. Clare’s poem speaks of the rural poverty caused by field-making for private gain and describes the great loss to its human neighbours: ‘There was a time my bit of ground Made freemen of the slave’; The poem also makes clear that the loss of common land and the more intensive usage of the countryside that followed was to the detriment of the ‘common’ as a diverse ecosystem with longstanding cultural overtones. Its ecosystems were managed haphazardly, but surely, by locally agreed custom. Beyond this, the global privatisation of common resources is treated as a fundamental loss to planet Earth itself:

‘ My only tree the’ve left a stump And nought remains my own’.

Irvine and Gorji view Clare’s poem as a total account of dispossession. It is striking in that it shows a human speaking from within a place, and in doing so gives the place a voice to speak on behalf of humans. In this process, the natural and the social consequences of privatisation designed ‘to make two blades of grass grow where there was only one before’, come to be intimately connected. Tim Dee also takes John Clare’s vision as his window into the cultural ecology of ‘fields and grass’:

“Just as fields aren’t famous, grass isn’t heroic of itself. It works anonymously. But I am trying to hear that as well. In John Clare’s great poem ‘The Lament of Swordy Well’ a put-upon, enclosed field talks back. It’s worth listening”.

3 Old Clee Fields: a case study for cultural conservation

The British Government’s geothermal aquifer project, which began in 1980, consisted of drilling experimental boreholes at four sites in England: Cleethorpes, Southampton, Marchwood, and Larne in Northern Ireland. The original plan for the Cleethorpes boreholes, where drilling started in 1983, envisaged that they would feed a district-heating scheme, supplying hot water to houses and schools. Water from a depth of 2000 metres proved to have too low a pressure for such a scheme, and water from shallower depths was not warm enough. However, the local authority held talks with horticulturalists and fish farmers who were interested in the business opportunities but the conclusion was that without government support, it was not economically feasible to tap the hot aquifer.

Cleethorpes’ geothermal resource came into the news again in 2014 when a local business man proposed to build a small community of 25 houses with greenhouses, which would be heated by a new borehole to be drilled in the village of Old Clee, about 3 miles from the Cleethorpes exploratory site. This new project was to be developed in a cul de sac on five acres of land known as ‘Horse’s Fields that can only be reached through Church Lane. The plans for the increased urbanisation of Old Clee triggered an immediate response from the residents who launched a campaign to oppose the development based on the traffic issues in Church Lane and the loss of a local green resource. Regarding the latter, one of the two Horse’s Fields is the remains of a very extensive pasture which was part of Greetham’s dairy farm until it was was developed for a school and houses after the Second World War. In particular, it was a textbook example of ridge and furrow cultivation dating from the time when Old Clee was organised as a medieval open-field system, which operated until the mid-19th century. Under the Enclosure award of 1846 the open fields in Clee village and Cleethorpes were subdivided and shared between various landowners. Greetham’s Farm was appropriated in the 1930s for expanding the housing stock of Grimsby, then the largest fishing port in the world.

Grimsby’s population growth had started with the onset of industrial fishing resulting from the discovery of a cod/haddock bonanza on the North Sea Dogger Bank. This had brought my grandparents from the countryside to partake of Grimsby’s fabled riches available to farm labourers.

Greetham’s Fields is where my own musings on fields I do not own began as a child chasing butterflies through the grassy flower-rich ridge and furrow pasture, then overlooked by Old Clee Church. My time scale as a second generation Grimbarian was greatly expanded when I discovered a thin band of seashells about a foot below the soil, when digging into the field’s deep ditch sides. Old Clee by virtue of the Saxon Tower of its church was really old, but not as old as the tidal estuary that in past times had reached within a few hundred yards of clay ridge where the church stands. Now, that beach is three to four miles away. Going further back in time there is the large glacial erratic ‘Wishing Stone’ dropped off by melting ice in Church Lane, a pointer to a prehistoric time-out- of-mind when the site of my butterfly fields were scoured sterile by glacial action.

Therefore the five acres of Horse’s Fields awaiting a planning decision are symbolic to me as the remains of a grassed universe where I roamed freely as a young body during the Second World. Every blade of grass I cherished, along with the ditches and hedgerows that were then brimming with wildlife. Brian Patten’s poem ‘A Blade of Grass’ expresses the idea that when we are young we tend to believe in the concepts of love, truth, and beauty. Even a blade of grass will be accepted in lieu of a poem when a lover offers it to his young beloved. But as we grow older we become cynical and even a ‘blade of grass /becomes more difficult to accept’, for the calculating mind will dismiss its value as merely ‘grass’, nothing more and nothing less. Unfortunately, local planning committees are composed of calculating minds attempting to make a choice between nature conservation and developments that win votes but in the long run are not sustainable.

You ask for a poem.

And so I write you a tragedy about

How a blade of grass

Becomes more and more difficult to offer,

And about how as you grow older

A blade of grass Becomes more difficult to accept.

(‘A Blade of Grass’ – Love Poems. Brian Patten; p. 23)

If, like Tim Dee, I had to choose a field that symbolises a personal and a global loss of contact with nature, because I am, like all humanity, a part of nature in everything I do, the first choice would be the Old Clee Horse’s Fields. They are the pathetic remains of what seemed to me a vast expanse of ‘Greethams Fields’ as I knew them as the playground of a small boy herding butterflies. To me they encapsulate the devastating outcomes of the relentless socio-economic pressure of urbanisation, which we all love and hate. It is hateful because it destroys grass.

4 The cultural value of grass

Small, semi-wild grassed habitats in human communities have a cultural value greater than that of their biodiversity. From this point of view, Old Clee is not short of grass, being adjacent to a large grass-based open air recreation complex cut regularly by power mowers. The ecological call of grass in the temperate zone is ‘eat me’ or ‘cut me’ else ‘I will revert to scrub and eventually become woodland’. To arrest this ecological process called succession recreational grassland is cut frequently to maintain a standardised low diversity baldness. In this respect, Horse’s Fields are grass because they were originally grazed by cattle as part of Greetham’s dairy farm and then by pet horses.

If the planning application for the housing estate fail, the objective of the residents could be to raise funds to purchase the fields and manage them in perpetuity as a community ‘cultural reserve’, not by grazing livestock but by taking an annual crop of hay. Haymaking is not only good for biodiversity but it also celebrates the culture of grassland farming that has played an important role in European social history. For five millennia haymaking has been a crucial part of human existence and an important catalyst in the cultural transformation of humans from hunters to herders. Unlike other agrarian inventions, which were part of the origin and dispersal of agriculture, haymaking was developed by Neolithic peoples without requiring the trial and error domestication of specific plants. Nutrient-rich cereal grasses were selected for arable production systems; fodder grass grew from the wild wherever livestock grazed. Cutting, sun-drying and storing native fodder for family herds helped save herders and their herds from seasonal deprivation, slaughter or migration. The surplus preserved as hay allowed animals and their human dependents to survive cyclical duress, or seasons and years of insufficient rainfall or sunshine. The hayfield became a picturesque arena of communal, seasonal work and provided visual texture and depth to the patchwork of summer fields. Haycocks, stacks and bales of various size and shape, have challenged generations of artists, diverse in style and philosophy, with their subtle sculpture, colour and reflectivity. It is constantly changing and easily lost because it exists only in our minds.

A hayfield is a response of an ecosystem to human intervention. To maintain its conservation/heritage value for the contemplation of urban dwellers requires the skilful use of the haymaker’s scythe.

The even mead that erst brought sweetly forth

The freckled cowslip, burnet and green clover

Wanting the scythe, all uncorrected, rank

Conceives by idleness, and nothing teems

But hateful docks, rough thistles, keksies, burs,

Losing both beauty and utility.

(Shakespeare, Henry V)

For communities contemplating adopting haymaking to connect directly with nature, communally and individually, there are many community projects available to emulate. For example, here is what George Peterken says about his parish grasslands project.

“Last week I went to Shirenewton to talk to the local history society about meadows and traditional haymaking. It was arranged a year ago, but it turned out to be well timed, for Shirenewton village has just acquired land for a village meadow. The village has two centres, separated by small fields, and it is for these that the community raised a nearly-six-figure sum. I did not see the field itself, but I understand that its a pleasantly flowery meadow with lots of colour but no great rarities, and that it is studded with 25 oaks – a meadow-parkland, in fact. The idea is that this will remain a public open space; that it will be treated as an ordinary meadow with grazing after the hay has been taken; and that it will be used for teaching by the local school. In the not-too-distant future, I hope to be invited to a village haymaking gathering, one of the lost traditions of rural Britain. An example for our own community?”

We can reinforce this message by turning again towards John Clare’s spirituality that comes from his deep sensing of nature:: ’

Tis haytime and the red-complexioned sun

Was scarcely up ere blackbirds had begun

Along the meadow hedges here and there

To sing loud songs to the sweet-smelling air

Where breath of flowers and grass and happy cow

Fling o’er one’s senses streams of fragrance now

Spirituality of grass is rooted in culture.

To the American poet Walt Whitman grass symbolised all humans, collectively and individually. The man in Whitman’s poem ‘Song of Myself’ “…observing a spear of summer grass.” causes him to ponder the human condition and the collective thoughts and actions of human beings. This blade of grass is amongst an innumerable host of leaves of grass like itself. It is a representation of a mass of individuals dependent upon their common root, as well as each being distinct and separate as a single blade from the surrounding multitude. So we humans are all part of a global host but we are also distinct, unique individuals. When we ponder a blade of grass we can think about ourselves, exemplified by the blade. and our purpose on Earth as individuals and a species.

“Song of Myself” can be interpreted as a call to experience the variety of life by ‘deep listening’ to grass. The message is that through the senses one can find long-term fulfillment and freedom from the mundane tasks of day-to-day living, which continue as background noise.

The section of the Whitman’s poem about grass opens when a child carrying bunches of grass asks the poet “What is the grass?” and Whitman is forced to explore his own use of symbolism to encapsulate nature. Thus, the bunches of grass in the child’s hands become a symbol of regeneration in nature. But they also signify a common material that links disparate people together. Grass is the ultimate symbol of democracy, it grows everywhere. Grass is also a reminder of mortality because it feeds on the remains of the dead. He concludes that the natural roots of democracy sprout from mortality, whether due to natural causes or to the bloodshed of internecine warfare. Old ideas die with the individuals who held them and democracy comes from revolution. We are at one with the bunches of grass because we are of the same biochemistry; we have the same pulse driving identical atoms of a dancing cosmos. We become other as other becomes us in an endless dance of engagement and revelry with the common stuff of life and stars. The very soil that nourishes the “blade of grass” transpires water, generating oxygen, thus endlessly representing the “journeywork of the stars.” In this sense, Whitman alludes to the fact that we come from the dust of the universe and, “My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air, …” We are at one with nature in that the soil begets a multitude of grass; the soil begot human beings through a creative act regardless of one’s belief system.

Grass is therefore a central symbol of this poem and stands for the sacredness of common things. Because we are thinking animals we are able envisage the nature and significance of grass unfolding the important themes of death and immortality, for grass is symbolic of the ongoing cycle of life present in nature. It is the key to the secrets of humanity’s relationship with the cosmos because we all have a chemical connection with the elements of nature and the universe. We have brotherhood with the most commonplace objects, such as leaves, ants, and stones, within an expanding cosmos. Whitman’s senses convince him that there is significance in everything, no matter how small.

Sections 31-33 contain a catalogue of the infinite wonders in small things. He believes, for example, that “a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars” and “the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery.” All things are part of the eternal wonder of life and therefore even “the soggy clods shall become lovers and lamps.” He, himself, incorporates an unending range of things, people and animals. Now he understands the power of his vision which ranges everywhere: “I skirt sierras, my palms cover continents,/I am afoot with my vision.” Especially in sections 34-36, he identifies himself with every person, dead or living, and relates his involvement with the various phases of American history. Realising his relationship to all this makes him feel, as he states in section 38, “replenish’d with supreme power, one of an average unending procession.”

His meditation on grass is an explanation of life and existence, “the puzzle of puzzles . . . that we call Being.” Here, grass is a symbol of the sacred latent in the ordinary, common life of humankind and it is also a symbol of the continuity inherent in the life-death cycle. No one really dies. Even “the smallest sprout shows there is really no death,” that “all goes onward and outward . . . /And to die is different from what any one supposed.”

In Section 7 the poet signifies his universal nature, which finds it “just as lucky to die” as to be born. The universal self finds both “the earth good and the stars good.” The poet is part of everyone around him. By contemplating grass he sees all and condemns nothing. Sections 8-16 lists all that the poet sees – people of both sexes, all ages, and all conditions, in many different walks of life, in the city and in the country, by the mountain and by the sea. Even animals are included. He not only loves them all, he is part of them all: And these tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them, And such as it is to be of these more or less I am, And of these one and all I weave the song of myself.

Whitman is representative of all humanity because, he says the voices of diverse people speak through him – voices of men, animals, and even insects. To him, all life is a miracle of beauty. Section 17 again refers to the universality of the poet – his thoughts are “the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands.” Sections 18 and 19 salute all members of humanity. Contemplating the meaning of grass in terms of mystical experience, the poet understands that all physical phenomena are as deathless as the grass.

(Old Clee residents gathering at Horse’s Fields)

Tim Dee (2013): ‘Four Fields’. Random House.

http://www.academia.edu/3629203/John_Clare_in_the_Anthropocene

http://www.suffolkkemps.info https://sites.google.com/site/hyperboxclub/whose-india

http://www.parishgrasslandsproject.org.uk/blog.htm

http://grass-scan.wikispaces.com/Grass+SCAN