The tree is a powerful symbol. Trees appear in many creation stories, such as the World Ash or the Garden of Eden. Religions, especially the Druids, have revered trees. Buddha was enlightened sitting under a Bodhi tree. Christmas is celebrated by decorating Christmas trees. There are sacred trees throughout the world. “Family tree” has a symbolic connection to the theme of immortality. Myths and symbols are the carriers of meaning. In them, a situation is presented metaphorically in a language of image, emotion, and symbol. Because human beings share a collective unconscious (C. G. Jung’s psychological explanation) or the Homo sapiens morphic field (Rupert Sheldrake’s biological explanation), a symbol comes from and resonates with the deeper layers of the human psyche.

Jean Shinoda Bolenhttp://www.dailyom.com/library/000/002/000002551.html

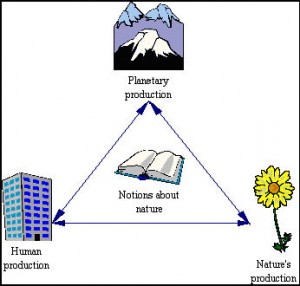

Human behaviour. from gathering food to mountain climbing, is now a major influence on all Earth’s ecosystems. There is no longer any wildness defined as ‘beings without people’. The term naturalness is used to define conditions in parts of our planet’s surface that for the time being happen to be relatively free of major human ecological interventions. Naturalness is largely the outcome of those processes of wildness that remain in the absence of human utilitarian activities. Nature sites are selected to represent naturalness. It is in these places that nature becomes the incarnation of human thought about our place in nature and nature’s resilience. In this connection, through the ages and in all corners of the globe, people have looked to trees to make sense of their lives, honouring their transcendental qualities in a variety of ways. How has our cultural attachment to, and interconnectedness with, trees manifested itself in the world today?

1 Evolution with trees

Many people take an understandably human-centered view of primate evolution, focusing on the bipedal, large-brained hominids that populated the jungles of Africa a few million years ago. But the fact is that primates as a whole, including not only humans and hominids, but monkeys, apes, lemurs, baboons and tarsiers, have a deep evolutionary history that stretches as far back as the age of dinosaurs.

The first true primates evolved about 55 million years ago, at the beginning of the Eocene Epoch. Their fossils have been found in North America, Europe, and Asia. They were still somewhat squirrel-like in size and appearance, but had grasping hands and feet that were increasingly more efficient in manipulating objects and climbing trees. The position of their eyes indicates that they were developing more effective stereoscopic vision as well.

Smilodectes (lemur-like family Adapidae from the Eocene Epoch)

Among the new primate species were many that somewhat resemble modern prosimians such as lemurs, lorises, and possibly tarsiers. The Eocene was the epoch of maximum prosimian adaptive radiation. There were at least 60 genera of them that were mostly in two families, one similar to lemurs and lorises and the other like galagos and tarsiers. This is nearly four times greater prosimian diversity than today. Eocene prosimians also were much more widely distributed around the world than now. They lived in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. The great diversity of Eocene prosimians was probably a consequence of the fact that they did not have competition from monkeys and apes since these latter more advanced primates had not yet evolved.

Major evolutionary changes were beginning in some of the Eocene prosimians that foreshadow species yet to come. Their brains and eyes were becoming larger, while their snouts were getting smaller. At the base of a skull, there is a hole through which the spinal cord passes. This opening is the foramen magnum. The position of the foramen magnum is a strong indicator of the angle of the spinal column to the head and subsequently whether the body is habitually horizontal (like a horse) or vertical (like a monkey). During the Eocene, the foramen magnum in some primate species was beginning to move from the back of the skull towards the center. This suggests that they were beginning to hold their bodies erect while hopping and sitting, like modern lemurs, galagos, and tarsiers

Sometime around six or seven million years ago, the first members of our human family, the Hominidae, evolved in Africa. Their anatomy suggests they spent much of their time in trees, as did their close primate relatives, the ancestors of today’s chimpanzees and gorillas. But unlike other primates, these early hominids walked readily on two feet when on the ground, a trait often used to define the human family.

Over the last decade, there have been a number of important fossil discoveries in Africa of what may be very early transitional ape/hominins, or proto-hominins. These creatures lived just after the divergence from our common hominid ancestor with chimpanzees and bonobos, during the late Miocene and early Pliocene Epochs. The fossils have been tentatively classified as members of three distinct groups dating from 7-6 million to 5.8-4.4 million years ago. It is uncertain as to whether any of these three types of primates were in fact true hominins and if they were our ancestors.

Humans are descended from australopithecines. The earliest australopithecines very likely did not evolve until the beginning of the Pliocene Epoch in East Africa. The primate fossil record for this crucial transitional period leading to australopithecines is still scanty and somewhat confusing. However, by about 4.2 million years ago, unquestionable australopithecines were present. By 3 million years ago, they were common in both East and South Africa. Some have been found dating to this period in North Central Africa also. As the australopithecines evolved, they exploited more types of environments. Their early proto-hominin ancestors had been predominantly tropical forest animals. However, African forests were progressively giving way to sparse woodlands and dry grasslands, or savannas. The australopithecines took advantage of these new conditions. In the more open environments, bipedalism would very likely have been an advantage.

By 2.5 million years ago, there were at least two evolutionary lines of hominins descended from the early australopithecines. One line appears to have been adapted primarily to the food resources in lake margin grassland environments and had an omnivorous diet that increasingly included meat. Among them were our early human ancestors who started to make stone tools by this time. The other line seems to have lived more in mixed grassland and woodland environments, like the earlier australopithecines, and was primarily vegetarian. This second, more conservative line of early hominins died out by 1 million years ago or shortly before then. It is likely that all of the early hominins, including humans, supplemented their diets with protein and and fat-rich termites and ants just as some chimpanzees do today.

Between the time of the first hominids and the period when our species, Homo sapiens, evolved in Africa more than 150,000 years ago, our planet was home to a wide range of early humans. To piece together their story, we rely on a wealth of evidence, including fossils, artifacts and DNA analysis. The web of clues is difficult to unravel, and experts often disagree about which species lived when and where. But it is clear that the human family has a rich evolutionary history; a past dwelling with trees that has shaped who we are today.

Geneticists have come up with a variety of ways of calculating how similar chimpanzees and humans are. The 1.2% chimp-human distinction, for example, involves a measurement of the base building blocks of genes that chimpanzees and humans share. A comparison of the entire genome, however, indicates that segments of DNA have also been deleted, duplicated over and over, or inserted from one part of the genome into another. When these differences are counted, there is an additional 4 to 5% distinction between the human and chimpanzee genomes.

No matter how the calculation is done, the big point still holds: humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos are more closely related to one another than either is to gorillas or any other primate. From the perspective of this powerful test of biological kinship, humans are not only related to the great apes – we are one! The DNA evidence tells us that the human evolutionary tree is embedded within the great apes.

The strong similarities between humans and the African great apes led Charles Darwin in 1871 to predict that Africa was the likely place where the human lineage branched off from other animals – that is, the place where the common ancestor of chimpanzees, humans, and gorillas once lived. The DNA evidence shows an amazing confirmation of this daring prediction. The African great apes, including humans, have a closer kinship bond with one another than the African apes have with orangutans or other primates. Hardly ever has a scientific prediction so bold, so ‘out there’ for its time, been upheld as the one made in 1871 – that human evolution began in Africa.

However, the traditional idea that our ancestors descended from the trees and gradually-and exclusively-began walking upright might be a gross over simplification. Fossil evidence from early hominins suggests that adaptations for tree climbing, such as long arms and fingers, coexisted with adaptations for upright walking, such as an arched foot and humanlike hips. Eventually, these upper-body climbing adaptations vanished and we became the adept striders that we are today. But how good are we at climbing trees now.

2 Culture with trees

Indigenous groups often climb trees to gather food without relying on chimp-like branch-climbing or supportive equipment. And though they’re not as good at climbing as chimpanzees, falls are only marginally higher (6.6 percent compared to 4 percent). To answer this question researchers studied two Ugandan groups-the Twa, who are hunter-gatherers, and the nearby Bakiga, who are farmers-and two Philippine groups-the Agta, who are hunter-gatherers, and the Manobo, who are farmers. Both groups of hunter-gatherers consume locally collected honey as an important part of their diets. Both groups climb trees to gather the honey, and many individuals start climbing at a young age. To ascend the trees, the climbers wrap their arms around the tree trunk at head-level, then, placing one foot in front of the other, the climbers advance upward to the honey source; in a sense, they “walk” up trees

Since the Neolithic period humans have struggled to open up forests for their cultures and livestock, little by little gaining living space for themselves. This was a long and battle, won with the help of fire, the plough and the unceasing teeth and hoof of farm animals. The remaining patches of woodland in Europe have not only a great heritage value, but also a symbolic one. The forest is a representation of wilderness in which we were launched as human, embedded in untamed nature with its unpredictable forces and its mystery.

European forests are not purely a mythical space, but also a physical reality, a large part of our cultural territory where the natural aspects of land dominate the man-made ones, where the wood production to meet our needs is compatible with the preservation of a great part of the biological diversity with which we evolved.

Even if most of our present tree scattered environment is largely managed and not comparable with the old natural forests that once covered Europe, it is still the habitat we share with of many other beings. Forest species contribute to about one-third of the biological diversity of Europe, as forest ecosystems represent the highest level of ecological structures, being complex and diverse in ecological function and form. As environments that early australopithicenes would have known. they have a great heritage value, as areas for human recreation, as landscapes, as providers of ecological services (clean water, prevention of erosion, carbon traps to combat climate change, etc.) and as privileged stages of spiritual contentment.

Until relatively recent times, forests have also been exploited for timber and other products – mushrooms, firewood, gathering of berries and nuts, game – for a very long time. The wide variety of wood from the different tree species has been used in many forms, for buildings, furniture, tools, arms, fencing. A superb wooden heritage has been created over the centuries in Europe, exploiting the beauty, suppleness or strength of wood.

Wooden heritage reckons its years in centuries. Few materials can lay the same claim to versatility as wood. This historically sustainable material, while at the same time flexible in all its applications, has adapted itself since prehistoric times to a variety of monumental, creative and functional expressions throughout our Europe. The technical and cultural differences in its use have benefited from the capacity of wood to be transformed combined with its resistance to the erosion of time. Surviving for centuries in spite of irreversible decay, wooden heritage was made one of the key areas of reflection during the “Europe, a common heritage” campaign.

Although not denying the functional aspect of wood as a material, it conveys some of the poetry implicit in its selection and in its symbolic meaning to those who shape it, decorate it, build with it or simply enjoy the fruits of the work of the virtuoso makers: from forest specialists to skilled artisans of musical instruments. We are dealing with a heritage of trees that corresponds to the craftsmanship of construction, the sociability of various forms of culture and respect for the landscape.

The wooden heritage constitutes an asset whose artistic and cultural values exceed the age of creators and curators. European wooden heritage is a living heritage supporting one of the most threatened forms of cultural expression and preservation of cultural heritage.

3 Trees and human conduct

Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau published his book, ‘Walden; or, Life in the Woods’ in 1854. It details his sojourn in a cabin close to Walden Pond, amidst woodland owned by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, near Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau lived at Walden for two years, two months, and two days, but Walden was written so that the stay appears to be a year, with expressed seasonal divisions. Thoreau did not intend to live as a hermit, for he received visitors and returned their visits. Instead, he hoped to isolate himself from society in order to gain a more objective understanding of it. Simplicity and self-reliance were Thoreau’s other goals, and the whole project was inspired by Transcendentalist philosophy. As Thoreau made clear in the book, his cabin was not in wilderness but at the edge of town, not far from his family home.

Walden emphasizes the importance of self-reliance, solitude, contemplation, and closeness to nature in transcending the “desperate” existence that, he argues, is the lot of most humans. The book is not a traditional autobiorgraphy but combines autobiography with a social critique of contemporary Western culture’s consumerist and materialist attitudes and its distance from and destruction of nature. That the book is not simply a criticism of society, but also an attempt to engage creatively with the better aspects of contemporary culture, is suggested both by Thoreau’s proximity to Concord society and by his admiration for classical literature. There are signs of ambiguity, or an attempt to see an alternative side of something common — the sound of a passing locomotive, for example, is compared to natural sounds.

The book is informed by American Transcendentalism, a philosophy developed mostly by Thoreau’s friend and spiritual mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson owned the land on which Thoreau built his cabin at Walden Pond, and Thoreau often used to walk over to Emerson’s house for a meal and a conversation.

Thoreau regarded his sojourn at Walden as a noble experiment with a threefold purpose.

First, he was escaping the dehumanizing effects of the industrial revolution by returning to a simpler, agrarian lifestyle. However, he never intended the experiment to be permanent, and explicitly advised that he did not expect all his readers to follow his example, and never wrote against technology or industry as such. Second, he was simplifying his life and reducing his expenditures, increasing the amount of leisure time in which he could work on his writings (most of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers was written at Walden). Much of the book is devoted to stirring up awareness of how one’s life is lived, materially and otherwise, and how one might choose to live it more deliberately — possibly differently. Third, he was putting into practice the Transcendentalist belief that one can best transcend normality and experience the Ideal, or the Divine, through nature.

It is an example of the integrative meme of spiral dynamics. Spiral Dynamics argues that human nature is not fixed: humans are able, when forced by life conditions, to adapt to their environment by constructing new, more complex, conceptual models of the world that allow them to handle the new problems. Each new model transcends and includes all previous models. According to Beck and Cowan, these conceptual models are organized around so-called vmemes (pronounced “v memes”): systems of core values or collective intelligences, applicable to both individuals and entire cultures.

The final chapter is more passionate and urgent than its predecessors. In it, Thoreau criticizes Americans’ constant rush to succeed, to acquire superfluous wealth that does nothing to augment their happiness. He urges us to change our lives for the better, not by acquiring more wealth and material possessions, but instead to “sell your clothes and keep your thoughts,” and to “say what you have to say, not what you ought.” He criticizes conformity: “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.” By doing these things, men may find happiness and self-fulfillment.

“I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but such is the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can never make to dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.”

Queen of the forest canopy

Nalini Nadkarni has been called “the queen of forest canopy research,” a field that relates directly to three of the most pressing environmental issues of our time: the maintenance of biodiversity, the stability of world climate, and the sustainability of forests.

For three decades, she has climbed trees on four continents, using mountain-climbing techniques, construction cranes, walkways, and hot air balloons to explore the world of animals and plants that live in the treetops. In 1994 she realized that there was no central database for storing and analyzing the research she was gathering, so she invented one. This state-of-the-art repository, called the Big Canopy Database, is credited with speeding cross-disciplinary collaboration just as a common database revolutionized the mapping of the human genome.

Nadkarni, the Director of the Center for Science and Math Education at The University of Utah, is known for using nontraditional pathways to raise awareness of nature’s importance, working with artists, dancers, musicians, and even loggers. Her work has been featured in Glamour, National Geographic, on TV, and in a giant-screen film, as well as in traditional science publications.

In a recent talk, Life Science in Prison, Nadkarni shares her findings from a partnership with the Washington State Department of Prisons which demonstrates that nature and conservation can have a tangibly positive impact on the planet, society and the inmates, themselves. There are currently 2.3 million incarcerated men and women in the U.S? And that 60% of all released inmates end up returning to prison? Nadkarni theorized that nature could help move the static and stuck prison system. So she provided science lectures. And the men, amazingly, chose coming to the lectures instead of watching television and lifting weights. She partnered with conservancy organizations to replant prairies and grow endangered frogs for later release into protected wetlands.

She worked with some of the most dangerous criminals to add calming images of nature to solitary confinement facilities

Nalini boils it all down to this: “When we come to understand nature, we are touching the most deep and most important parts of ourself.”

We can take this as an example of humankind having reached the level of the holistic meme. We experience the wholeness of existence through mind and spirit Everything connects to everything else in ecological alignments. Energy and information permeate the Earth’s total environment. Self is both distinct and a blended part of a larger, compassionate whole. Holistic, intuitive thinking and cooperative actions are to be expected.

– See more at:

http://www.thepromisedland.org/episode/5-nalini-nadkarni#sthash.KokNA2CP.dpuf

http://www.ted.com/talks/nalini_nadkarni_life_science_in_prison