Marketing to the emotions: UKIP’s leader with his ‘battle bus’

“Mental models are personal, internal representations of external reality that people use to interact with the world around them. They are constructed by individuals based on their unique life experiences, perceptions, and understandings of the world. Mental models are used to reason and make decisions and can be the basis of individual behaviors.

Natalie A Jones, Helen Ross , Timothy Lynam , Pascal Perez and Anne Leitch (2011)

1 Mental cultural ecologies

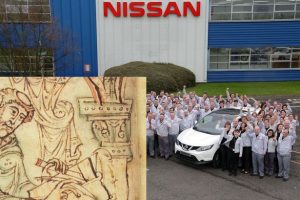

Two weeks before the 2016 British European Union referendum, Helen Pridd, North of England editor of the Guardian newspaper, interviewed young men among 1,000 apprentices employed by Nissan in their Sunderland car plant. About 8000 local people are directly employed in the vast manufacturing complex, with 32,000 more jobs in the supply chain. More than 70% of the half a million cars produced in Sunderland each year are exported to Europe, mostly to EU members.

She writes:

“Taking a cigarette break outside the enormous Nissan factory in Sunderland last week, Martin Winyard was adamant he would be voting to leave the European Union. Never mind that his bosses at the car plant had made it clear they would much rather see Britain stay in the EU.

The 19-year-old apprentice wanted out.

“We’re being taken over by foreigners,” he said. “People from Israel, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria; they all end up living here.”

A colleague, Mark Willshire, pointed out that none of those countries were actually in the EU.

But Winyard’s mind was made up: “My great grandad fought for British independence. We shouldn’t let foreigners take over now.”

Helen Pridd continues,

“Sunderland is a city ranked as among the most Eurosceptic in Britain. Despite the north-east of England receiving large amounts of European funding and its buoyant car industry exporting most of its vehicles to the EU, widespread Europhobia is causing the remain campaign serious jitters two weeks before the referendum.

Kevin Guthry, 59, who is on the Nissan apprenticeship scheme as a condition of collecting jobseeker’s allowance, said he too would be voting to leave.

“Look at all these lads,” he said, gesturing with his lit cigarette, “these lads are here because they can’t get real jobs because of all the immigrants.”

Guthry is a life-time Labour voter, but not any more. “I don’t like the new leader. It’ll be Ukip for me next time.”

The actual result of the Sunderland referendum was 82,394 for Leave to 51,930 for Remain – a majority of 61% on a 64% turnout. What we don’t know is how many off Nissan’s work force voted to leave the EU. Nor do we know how many of NIssan’s workers actually live in Sunderland.

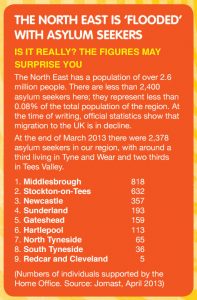

The facts are that migrant asylum seekers in Sunderland and its surrounding communities are in their hundreds within an indigenous population of thousands (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1 Presenting the facts

At about the same time that Helen Pridd was interviewing Nissan’s apprentices in Sunderland, the ‘New Scientist’ predicted that uncertainty over the future and contradictory political information will mean voters in the UK’s EU referendum would be swung even more than usual by emotional feelings and biases in data presentation. In their article ‘Brexitology: What science says about the UK’s EU referendum’, Michael Bond, Jacob Aron and Hal Hodson stated that the EU referendum could be the most irrational yet. They said that uncertainty over consequences, and contradictory economic and political information, mean that voters will be swung even more than usual by feelings and biases that have nothing to do with the issues at stake. They quoted John McCormick an American expert on EU politics: “Polls show that knowledge about the EU in Britain is low. To a large extent it’s going to be a domestic protest vote”. He predicted that instead of EU considerations, many voters will be guided by their entrenched views on immigration, the Conservative government and political figures such as David Cameron, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage.

Post referendum surveys show that McCormick turned out to be right on all counts. Furthermore, only 22% of voters understood the implications of what they were voting on. Referendums are not elections, but because of their rarity, parties campaign as if they were, elevating personalities and emphasising differences. Voters in referenda like to see parties and experts from credible civil society organisations working together, offering insights and sharing analysis, and calling a lie a lie, rather than bickering or one-upping each other by meeting facts with unsubstantiated assertions in sound bites.

2 An illusion of shrinkage

During the past 30 years, it has become a cliché to declare that ‘the world has become a smaller place. Climates have changed, water levels have risen and mass tourism, for some, continues to expand and proliferate. This has had an effect on popular perceptions of time and space which, fanned by the effects of the digital revolution, the speed of the internet and the pervasive influence of social media, have created an illusion of shrinkage. Vast shifts of capital and production, from West to East, from North to South, have changed the world’s economic map and their ultimate political, economic and cultural effects are far from clear. However, one thing is certain, inequalities have not been eliminated It is estimated that 17% of the world’s total population is living in extreme poverty. Furthermore, extreme poverty is only a fraction of a much larger cycle of deprivation in which the gap between the majority and the super-rich is becoming ever larger. Its impact is already clear and growing. As environmental and political instability spreads across the globe there is little doubt that it will continue to feed into social and political conflict.

According to recent figures, just under half of Sunderland was ranked as being among the 20% most deprived areas in England, and more than a fifth of Sunderland ranked in the bottom 10%. Many of Sunderland’s children grow up in income deprived homes. Unemployment in the North-east of England is the highest in the UK, and the number of long-term unemployed in Sunderland continues to rise. Yet in terms of the UK well-being survey Sunderland is not exceptional, returning unremarkable lifestyle statistics on anxiety 3/10, happiness 7.3/10, a worthwhile life 7.7/10, satisfaction with life 7.4/10. There is not one general reason for people voting to leave the EC! The referendum required only a tick against ‘stay’ or ‘leave’, whereas people had a variety of reasons for wanting to stay or leave. These different reasons are now emerging through surveys of why people voted the way they did. However we will never know, for example, how many people voted against immigration, or, for that matter, any of the freedoms the EU guarantees for members of what it calls its community.

Most historians think of community as formed mainly within a bounded area in which virtually everybody knew each other, to which people felt that they belonged, and which commonly had administrative functions. Now, more than ever, people are subjected to misinformation, disinformation and propaganda every single day. Many of the decisions individuals make will be based on that person’s misperceptions of life and the way they see it, either because of misinformation or the absence of information. Cognitive dissonance is the state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioural decisions and attitude change. Basically it happens when reality does not match up with our behaviours.

It would be amusing if it weren’t for the destructiveness that wrong perceptions of people and situations can cause. What is amusing is that, like the Nissan apprentices, we are all convinced of the truth of our perceptions and act on them accordingly, despite the inaccurate and incomplete way the brain works to give us these perceptions. The sad reality is that most of our perceptions of other people and situations are very distorted. Even if we do not move our body, our thoughts and consciousness are constantly moving away to find a life elsewhere. Yet we now have location-free ‘imagined’, ‘communication’, ‘simulated’, or ‘virtual’ communities and there are some theorists who believe that these are communitarian improvements on, and better substitutes for, the past. So many people now live outside territory and community as defined by local space, at least for part of their time. Indeed, to be local is thought by many to be a sign of social deficiency and degradation, of marginalisation and constraint. Measures of ‘the quality of life’ even stigmatise localism and a failure to be mobile as ‘deprivation’, and seriously formalise that judgement in the form of quantitative indicators.

In response to mental irrationality, barriers between individuals and groups have been torn down, while others of different kinds have been erected. Differences between past and present in respect of ‘belonging’ are now so great for many people, as ‘organic’ communities and forms of local territorial thought and practice disintegrate worldwide before waves of cultural contact, rapid transport, economic extension and financial speculation. In particular, the 2016 UK referendum has revealed the existence of local diversity between communities, where a common factor is fear of strangers

3 The working community

Fig 2 The beginning and end of Sunderland’s heritage

There is widely accepted belief that having a strong cultural heritage is necessary for local well-being. The Royal Society of Arts think tank, in collaboration with the UK Heritage Lottery Fund has produced a Heritage Index that reveals which areas enjoy the most physical heritage assets; how actively residents and visitors in those areas are involved with local heritage; and, by comparing the two, the indices show where there is potential to make more of heritage. When comparing the combined ‘overall’ heritage scores of all 325 English districts against the national Index of Multiple Deprivation, the RSA found there to be no correlation. Several places were found to be rich in local heritage and involvement despite being relatively poor communities with low self esteem. Sunderland’s Heritage Index falls into the bottom 30%. A few miles down the coast, the area around the fishing port of Scarborough, which also includes Whitby, has an Index falling in the top 1%. Yet in 2015 Scarborough’s Index of Multiple Deprivation indicated that it was the most deprived district in North Yorkshire. Three areas in Scarborough town are within the most deprived 1% in England (parts of Woodlands, Eastfield and Castle wards).

There can be no doubt that Sunderland’s cultural heritage has a very rich narrative, from Bede to Nissan (Fig 2). Sunderland was once known as ‘asunder-land, that is land cut asunder, separated or put to one side. This is probably a reference to the fact that the community developed from Saxon migrants taking up opposite positions on the north and south banks of the River Wear where it enters the North Sea. Although there is continued dispute over whether Sunderland is a city of Roman origins, we do know that by the early medieval period there were three small settlements along the River Wear: South Wearmouth (opposite the Saxon monastery, which later became Sunderland fishing village), Bishopwearmouth (probably a Saxon village) and Monkwearmouth Village on the north bank, based around the monastery founded by Benedict Biscop in 674. In 1835 the three settlements were officially merged to become the Parliamentary Borough of Sunderland, now the City of Sunderland.

Biscop’s monastery was the first to be built of stone and is one of the oldest ecclesiastical buildings still being used in England. While at the monastery he employed glaziers from France and in doing so he re-established the skills of glass making in Britain, which were lost with the end of the Roman occupation. In 686 the monastic community came under the rule of Ceolfrid,an Anglo-Saxon Christian abbot and saint. He is best known as the guardian of the most accomplished monk of Saxon times, St Bede. Ceolfrid was the guardian of the young Bede from the age of seven until his death in 716.

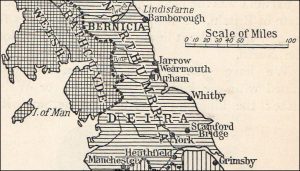

Fig 3 Communities fishing the North Sea East cost

By that time Wearmouth had become a major centre of learning and knowledge in Anglo-Saxon England with an exceptional library of around 300 volumes The Codex Amianatus, that has been described as the ‘finest book in the world’,was created at the monastery and was likely worked on by Bede. Bede himself completed the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (The Ecclesiastical History of the English People) in 731, a feat which earned him the title ‘The father of English history’.

Sunderland is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. By 1100 there was a fishing village at the mouth of the Wear, one of several small communities, dotted along the north east coast of the North Sea centred on families subsisting on inshore fishing (Fig 3 ).

The early 19th century saw development of Sunderland with new technology to sink deep shafts into the Durham Coalfields and Stephenson’s pioneer Hetton Colliery Railway carried coal to the Hetton Drops staithes at the mouth of the Wear. By the mid-C19th Sunderland was the biggest shipbuilding port in the world, with 65 shipyards in operation.

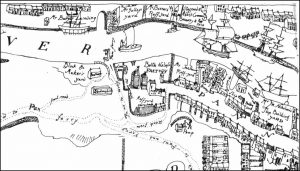

One of the industries which once thrived on South Tyneside, was glass-making. This was a lucrative trade, dating back to the 17th century, which was established by French Huguenot refugees fleeing persecution. In 1762 the Malying pottery was founded in Sunderland also by Huguenots (Fig 4 ).

Fig 4 Plan of Sunderland and Bishopwearmouth 1785-1790 showing the bottle and window- glass factory and shipbuilding yards

In remembrance of this glass making heritage Sunderland houses the National Glass Centre, an adjunct to Sunderland University.

The concept of a ‘working community’ of fisherfolk and its reciprocal networks, as historians sense it, is a mental construct. The French call it ‘an ecomene’. On the north east coast it is focussed in the mind through the pioneer photography of Frank Meadow Sutcliffe in Whitby, and the fiction of Leo Walmsley, who based his novels in Robin Hood’s Bay just south of Whitby. Thus, Sunderland and its neighbouring coastal communities provided the place models of strangeness, which arose from visits of 19th century photographers, artists and authors to the coastal fishing communities of the north east. At the turn of the 19th century, the artist Laura Knight described her mental attachment to the otherness of the fishing community of Staithes, a small village to the south of Sunderland:

“The life and place were what I had yearned for- the freedom, the austerity, the savagery, the wildness. I loved it passionately, overwhelmingly I loved the cold and the northerly storms when no covering would protect you. I loved the strange race of people who lived there, whose stern almost forbidding exterior formed such contrast to the warmth and richness of their natures…. It bordered on the theatrical”.

The inward looking Victorian ecomene described by Knight has now ceased to exist. Indeed, most of those visiting such places were themselves documenting the decline of the unified working community. However, the concept of ‘working community’ still exists as a desirable mental ecology in the minds of those who have seen pictures and read some of the novels. It stands in the words of Knight as a counterweight to the urban lives most people are immersed in yet are seeking something better, They are pondering questions of what kind of real living should replace this mental localism and how viable for human needs the engineered replacements will be.

4 Mental localism

“All good people agree,

And all good people say,

All nice people like Us, are We

And everyone else is They;

But if you cross over the sea,

Instead of over the way,

You may end by (think of it!)

Looking on We

As only a sort of They.”.

— Rudyard Kipling, The fifth and last verse of “We and They,” 1926.

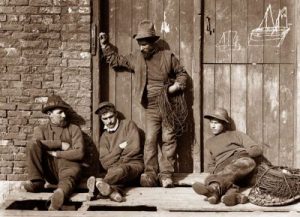

Geographically, the East Coast settlements of Staithes, Runswick, Whitby, Robin Hood’s Bay, Scarborough, and Filey, comply with the principal constraint of ‘them’ as models of mental localism. They are discrete settlements linearly arranged along the cliff-girt coast wherever there is a break in the cliff face to access a beach suitable for launching small family owned sailing boats. They are but a few of the links in a much longer chain of coastal settlements which stretched from Brixham in Devon to John o’Groats in Scotland. Migration is restricted on one side by the sea, and on the other by the North Yorkshire moors. However, it was by sea that migrants arrived. They were families moving up from the English Channel fishing grounds, with their innovations in engine powered boats and more effective fishing tackle. It was at this point of social interaction of the old with the new that Leo Walmsley set his novels ‘Three Fevers’ and ‘Sally Lunn’ that describe the rivalry between backward looking fishing families and the southern migrants with their new ways. A process of mental localism was also at work when Frank Sutcliffe pointed his camera at places and people to produce images set in Staithes, Whitby and Robin Hood’s Bay. He was a leading award winning naturalistic photographer in Victorian England. Working during the last three decades of the nineteenth century, he operated a portrait studio in Whitby, but was better known for his sensitive images of its port and everyday people. Sutcliffe also photographed abbeys and castles throughout Yorkshire for the country’s leading commercial firm, Francis Frith and Company. Because of the low sensitivity of the camera a plates of the time he posed his human subjects in carefully designed positions they had to hold for minutes at a time (Fig 5 )

Fig 5 Whitby fishermen (circa 1890) Frank Meadow Sutcliffe

Pictures of grouped figures such as Sutcliffe’s Whitby fishermen are not only attractive because of the way they have been composed, interlocked in their gazes indicative of a decisive moment and a time of heightened social tension, but also because of their strangeness in dress and surroundings. As a general rule, “difference” is associated with “strangeness” and can lead to the dread of foreigners as a group, whether defined legally, as immigrants, or by their strangeness as a visible group which the observer cannot join.

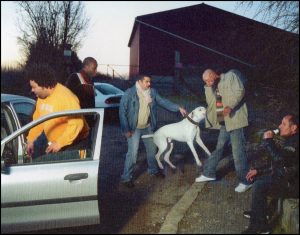

Social tension that can be read into photographs projecting the strangeness of grouped figures, is the basis of Mohamed Bourouissa’s art works (b.1978, Blida, Algeria). He is a contemporary artist whose practice explores social tensions within European migrant society. After moving to France from his native Algeria, he grew up in ‘les banlieues’, the suburbs of Paris that have become a byword for the ghettoisation of migrant communities. This experience shaped Bourouissa’s approach to image making, which is primarily concerned with representations of the contemporary urban environment and, in particular, geographic and social spaces prone to negative stereotyping.

‘Peripherique’ (2005-08), Bourouissa’s best known photographic series, directly addresses many of these preoccupations (Fig 6 ). Utilising a documentary photography aesthetic, Bourouissa defies the notion of a ‘decisive moment’ by carefully constructing scenes that use the residents and high-rise housing of the banlieues respectively as his protagonists. Like Sutcliffe’s compositions they are carefully arranged with people as set pieces. Bourouissa was influenced by the works of French romantic painters, such as Delacroix and Gericault (Fig 7), retaining what he describes as ’emotional geometry’ to display the natural interaction of his subjects to reveal moments of heightened tension. Sutcliffe and Bourouissa both deal with the interplay of truth and fiction acting as a provocation, creating a sense of apprehension and threat. The title of Bourouissa’s series refers both to the ring road encircling Paris and to those who are marginalised, physically and socially. The works of both photographers can be used as societal lenses to explore issues of exclusion, isolation, immigration and class.

Fig 6 ‘The Bite’: (photographic series 2005-8) Mohamed Bourouissa

Fig 7 The Murderers Carry The Body Of Fualdes: (1818) Theodore Gericault

5 Mental ecology and hatred

A survey of values and attitudes supports the common view that economic deprivation and its attendant social problems seem to promote anti-foreigner feeling. In the light of such surveys it is important to ask what critical perspectives might nurture the ability and the desire to live with difference on an increasingly divided, but also convergent planet? We need to know what sorts of insight and reflection might actually help increasingly differentiated societies and anxious individuals to cope successfully with the challenges involved in dwelling comfortably in proximity to the unfamiliar without becoming fearful and hostile.

In his book, ‘The heritage crusade and the spoils of history’, David Lowenthal argues that academics evaluate heritage using the same criteria they use to judge “good” history, such as verifiable observation. Yet because heritage and history are distinct ways of knowing the past, he believes that such assessments of heritage are baseless. “History explores and explains pasts that have grown more obscure over time; ‘heritage’ clarifies pasts so as to infuse them with present purposes”. By confusing these different routes to reclaim the past, he says, critics forget that heritage, no less than history, is a way of understanding our humanized worlds and that, as such, it provides individuals and groups with a sense of identity as well as the opportunity to forge common stewardship of a cosmopolitan heritage.

Lowenthal’s writings have focused on the paradoxical nature of attitudes and representations of the past. Although cultural expressions of heritage are produced to console groups and individuals with the presence of tradition, the production of heritage can also result in xenophobic hatred and chauvinistic nationalisms. Clarifying such problems and potentials of heritage is his main goal. Another more implicit goal is to criticize academics for their negative and cynical appraisals of the cult of heritage. Lowenthal suggests that the heritage industry in and of itself is not “bad”; rather, the actions that individuals perform in the name of heritage can promote tolerance as well as genocidal hatred of other peoples.

Despite its widespread usage, xenophobia is an ambiguous and contested term in popular, policy and scholarly debates. The interchangeable or complementary use of similar terms such as nativism, autochthony, ethnocentrism, xeno-racism, ethno-exclusionism, anti-immigrant prejudice and immigration-phobia further demonstrates this conceptual vagueness. Some scholars consider it to be intense dislike, hatred or fear of others, others only recognise it when it manifests itself as a visible hostility towards strangers or that which is deemed foreign. There are also ongoing debates on whether xenophobia emanates at the individual or collective level. While these approaches are unified by a generalised acceptance that xenophobia is a set of attitudes and/or practices surrounding people’s origins, the specific locus of debate and work is highly contextualised and often generally incomparable. Xenophobia for one analyst may be only tangentially tied to the xenophobia discussed by another.

Xenophobia becomes part of cultural ecology as the fear or hatred of foreigners and strangers; it is embodied in discriminatory attitudes and behaviour, and often culminates in violence, abuses of all types, and exhibitions of hatred. Studies on xenophobia have attributed such hatred of foreigners to a number of causes: the fear of loss of social status and identity; a threat, perceived or real, to citizens’ economic success; a way of reassuring the national self and its boundaries in times of national crisis; a feeling of superiority; and poor intercultural information. According to the latter argument, xenophobes are possessed by the past and presumably do not have adequate information about the people they hate and, since they do not know how to deal with such people. They see them as a threat. Xenophobia basically derives from the sense that non-citizens pose some sort of a threat to the recipient’s’ identity or their individual rights. It is also closely connected with the concept of nationalism: the sense in each individual of membership in the political nation as an essential ingredient in his or her sense of identity. To this end, notions of citizenship and political control can lead to xenophobia when it becomes apparent that the government does not guarantee protection of individual rights. This is all the more apparent where poverty and unemployment are rampant.

Whilst xenophobia has been described as something of a worldwide phenomenon, closely associated with the process of globalization, it has been noted that it is particularly prevalent in countries undergoing transition. This is thought to be because xenophobia is a problem of post-coloniality, one which is associated with the politics of the dominant groups in the period following independence. It is to do with a feeling of superiority, but is also, perhaps, part of a ‘scapegoating’ process, where unfulfilled expectations of a new democracy result in the foreigner coming to embody unemployment, poverty and deprivation. Theoretically, the best, and only, solution is to remove enemy images; however, it is debatable whether this can be done. Enemy images may have their origin in a variety of genuine or perceived conflicts of interest, in racial prejudices, in traditional antagonisms between neighbouring competing tribes or groups, in imagined irreconcilable religious differences and so on.

With respect to human social diversity, xenophobia is seen as a biological imperative in our hominid ancestors, ensuring the greatest degree of altruistic co-operation within social groups developing in isolation. Shunning outsiders would lead to the evolution of different languages and traditions which tend to stabilize tribes and ethnic groups. War, as the extreme outcome of xenophobia, sparks values of solidarity, egalitarianism and self sacrifice into tribal life.

Detaching the UK from the EU then comes down to how we can manage the behavioural mechanisms by which we humans define and protect our ecological niche. We see protection rests on mental differences between ‘us’ and ‘them’, which depend, paradoxically, on the social power of strangeness to fascinate us. However, there is a world of difference in the outcome of hanging one of Sutcliffe’s photographs of Whitby fishermen on the wall and abusing someone in the street. In the coming years, political effort will be devoted to negotiating a deal with the EU to opt out of the free movement of labour. The government’s intention is to release extra funding to tackle hate crime, to boost reporting of offences and to provide security at potentially vulnerable institutions. It is impossible to see how this will dampen division and fear that has surfaced by some in the “Leave” campaign who have stoked xenophobia and racism within the UK’s mental ecological niche.

6 Internet references

https://cityofsanctuary.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/ne_mythbuster.pdf

http://www.thecobleinart.com/victorianphotos.htm

http://www.ted.com/talks/nic_marks_the_happy_planet_index?language=en

http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/HTMLDocs/dvc238/index.html

http://www.thelovelyplanet.net/traditional-dress-of-zambia-rare-but-unique-in-nature/

http://www.theheritagealliance.org.uk/update/the-uses-of-the-heritage-index/