Fig 1 Queuing for ‘the sales’ at Howells department store in Cardiff.

“In the 1860s, twenty-year-old Denise Baudu and her two younger brothers, recent orphans, emigrated from a provincial French village to Paris, to live with their uncle. Arriving at daybreak after a sleepless night on the hard benches of a third-class railway car, they set out in search of their uncle’s fabric store. The unfamiliar streets opened onto a tumultuous square where they halted abruptly, awestruck by the sight of a building more impressive than any they had ever seen: a department store. “Look,” Denise murmured to her brothers. “Now there is a store!” This monument was immeasurably grander than her village’s quiet variety shop, in which she had worked. She felt her heart rise within her and forgot her fatigue, her fright, everything except this vision. Directly in front of her, over the central doorway, two allegorical figures of laughing women flaunted a sign proclaiming the store’s name, “Au Bon-heur des Dames” (“To the Happiness of the Ladies”). Through the door could be seen a landslide of gloves, scarves, and hats tumbling from racks and counters, while in the distance display windows unrolled along the street”.

From ‘Dream Worlds’ by Rosalind H Williams (1982)

1 Beginnings

The advent of mass consumption in South Wales represents a pivotal historical moment. Once people enjoy discretionary income and choice of products, once they glimpse the vision of commodities in profusion, they do not easily return to traditional modes of consumption. Having gazed upon the delights of a department store, Denise would never again be satisfied with the plain, unadorned virtues of Uncle Baudu’s shop. The hackneyed plot of the young innocent in the big city receives a specifically modern twist, for now the seduction is commercial. We who have tasted the fruits of the consumer revolution have lost our innocence.

In the domain of economics “consumerism” refers to economic policies placing emphasis on consumption. In an abstract sense, it is the consideration that the free choice of consumers, as dreamers of better things to come, should strongly orient the choice by manufacturers of what is produced and how, and therefore orient the economic organization of a society. In this sense, consumerism expresses the idea not of “one person, one voice”, but of “one dollar, one voice”. The outcome may or may not reflect the contribution of people to a sustainable society.

For many in the 19th century, it was the South Wales Coalfield that was the dream world for satisfying pent up desires to become a consumer. The expansion of the coal industry in the second half of the nineteenth century saw a huge increase in the population of the South Wales Valleys. Inequalities were greatest at the turn of the 18th century. For example, in 1760, Merthyr Tydfil, at the heads of the valleys, consisted of only 40 houses amidst a few farms of 30 to 35 acres worked by a single pair of horses with a basic set of cultivation equipment. This was considered sufficient to support a man and his wife without the need for a supplementary income. A large family, on the other hand, could hardly be sustained on a holding of this size unless some members took up by-employment and/or resorted to seasonal migration to the harvest fields of the English border counties. But four decades later, several thousand people had settled in Merthyr earning their living in the newly constructed mines and foundries.

According to a report on the town published in 1841, some 1,500 people lived in poorly constructed stone huts, often built on top of waste heaps of industrial waste. There were no toilets; the streets were open sewers; people were infested with lice and in such overcrowded conditions infections and diseases such as typhus, dysentery and cholera spread at terrifying speed. The cholera outbreak of 1848/49 killed 3,000 people in the county of Glamorgan. In Cardiff there was a total of at least 350 deaths. Merthyr Tydfil was the worst affected town, suffering a total of 1,389 deaths from cholera. The dead were quickly buried with little fuss, but public prayer meetings were constantly held.

Within the town, two thirds of the deaths occurred in Upper Merthyr, which had the highest levels of poverty and overcrowding: 160 died here in 1832; nearly 1700 in 1849, and 400 more in 1854. Even this understates the magnitude of the crisis in the town. Between 1851 and 1865, there was only one year (1860) when there was no epidemic.

Cholera was only one problem, coexisting as it did with typhus, smallpox, scarlet fever and measles. In the dreadful years of 1864 and 1865, all four of these diseases hit together; in 1866, cholera returned. The appalling sanitary conditions naturally contributed to high death rates. The Welsh rate was 20.2 per thousand in 1841, 22 in 1848, 25.8 during the cholera year of 1849. Not until the 1890s did the figure fall below 20.

Infant mortality, told a similar story of inequalities. It ran at 125 per thousand live births in 1839, and improvement was slow. The figure was at or over 120 until the 1880s, and fell below 100 only after 1910. The situation was also much worse in particular locations. In Cardiff, the death rate between 1842 and 1848 was 30 per thousand; and within such high-risk towns, there were still more unhealthy pockets, such as the Irish sections of Stanley Street and Love Lane. Merthyr recorded an overall rate of 30.2 per thousand in 1853, but this was far exceeded in neighbourhoods like ‘China’ or Tydfil’s Well.

For children dying before their first birthday, infant mortality in Merthyr was rarely below 190 per thousand in the 1820s or 1830s. However, the first five years of life were an exceedingly dangerous period. In the very worst years, such as 1823, burials of children under five were 713 for every thousand baptisms, 40 per cent above the normally dreadful rates.

But still the migrants came and things began to improve, Between 1851 and 1911, it is estimated that some 366,000 people moved into the Coalfield. The peak of this migration occurred between 1901 and 1911 when 129,000 people moved into the area. At this time South Wales absorbed immigrants at a faster rate than anywhere in the world except the United States of America. The goal of urban life was betterment of person and family, powered towards purchasing goals set by surplus income chasing the visions projected by mass advertising.

Up until the 1890s, many of the people who moved into the Coalfield were from other counties in Wales, such as the the totally rural areas of Cardiganshire, Montgomeryshire and Merioneth. After the 1890s, many more immigrants came from Somerset, Gloucestershire and Cornwall. People also came from further afield, such as Ireland, Scotland and even Australia. In Dowlais and Abercrave, there were communities of Spaniards. In Merthyr, there were small communities of Russians, Poles and French and in many of the Valley towns, Italians opened cafes to serve these newly forming valley communities with time on their hands.

Two statistics tell the story: in 1801 the population of Glamorgan was 70,879; in 1901 it was 1,130,668. In 1851, the population of the Rhondda coal community was 1,998 ; in 1911 it was 152,781.

Initially, for these settlers there was only the local pithead store stocked by the coalowner, who also rented them his newly built, tightly packed terrace houses. There was no choice but to take what was available on the owner’s terms. Freedom of choice came with the arrival of specialised shopkeepers; such as the butcher, the baker, the shoemaker and the milliner. The huge variety of jobs in the local economy at that time is evident from the numerous community trade directories that were published annually.

The next stage in economic freedom was the coming of the market hall in the nearest town and the stores of the national Cooperative Movement in smaller communities. These developments were evidence of a thriving consumer culture and an increasing demand for non-essentials that are purchased by choice rather than need.

Around this time the shopping arcade and the department store were French inventions. In Paris they were associated with the first appearance of poster advertising, with subtle hints that connected pleasure with a product to be purchased (Fig 2). Necessities and luxuries of all kinds were available in endless variety under one roof. These ultimate palaces of consumerism, finally reached Wales in the form of the massive Cardiff department stores of two local self-made retail entrepreneurs, James Howell and David Morgan. Shopping in a glamorous department store had become the goal of the newly arrived urban middle classes.

Fig 2 Advert for ‘Job’ cigarette papers Alphonse Mucha (1898)

2 Legacies

Then came the decline of the coal industry. Peak output of coal In South Wales occurred just before the First World War. During the period 1919 to 1939 there was mass unemployment. As a result, almost 500,000 people left the valley communities during the inter-war years seeking work elsewhere. The Rhondda, for example, lost around 36% of its population between 1921 and 1951. Many people went to towns in England such as Wolverhampton and Slough, where new manufacturing industries were developing. Others went further afield to the United States of America, Canada and Australia.

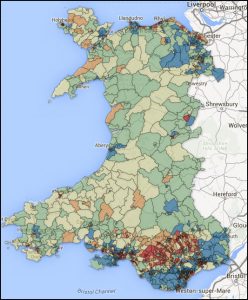

Now there are no deep mines but there is a legacy of pockets of neighbourhood deprivation, many of which are occupied by the descendants of those families that did not move away. These areas are defined by the Welsh Government’s Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD). This is the official measure of deprivation within small geographical areas, where it is a relative measure of concentrations of deprivation.

Deprivation is a wider concept than poverty. Poverty means a lack of money. Deprivation refers to wider problems caused by a lack of resources and opportunities. Therefore, WIMD is constructed from eight different types of deprivation. These are:

- income

- housing

- employment

- access to services

- education

- health

- community safety

- physical environment.

Wales is divided into 1,909 Lower-Layer Super Output Areas (LSOA) each having about 1,600 people (Fig 3). Super output areas are a geography for the collection and publication of small area statistics. They are used on the official Neighbourhood Statistics site and across National Statistics. Deprivation ranks have been worked out for each area: the most deprived LSOA is ranked 1, and the least deprived 1,909. One area has a higher deprivation rank than another if the proportion of people living there who are classed as deprived is higher.

An area itself is not deprived: it is the circumstances and lifestyles of the people living there that affect its deprivation rank. Not everyone living in a deprived area is deprived and not all deprived people live in deprived areas.

Fig 3 Distribution of deprived areas in Wales (2014)

Red = most deprived areas; Blue = least deprived areas

As the industrial legacy of South Wales began fading rapidly from sight and living memory there appeared a landscape of industrial despoliation and dereliction. Since the 1960s the growth of industrial archeology has rapidly transmuted spoil heaps, old mineral lines and pitheads into a post-industrial landscape envisioned as an environmental service for recreation and tourism.

As far as the global legacy of Welsh mining is concerned, in the wake of life with coal we now see that our burning of fossil fuel has released and continues to release enormous quantities of ancient carbon into the atmosphere. This has taken place with a relative suddenness, causing local, regional and global ecosystem harm and threatening abrupt and irreversible shifts in the state of the planetary ecosystem as critical ecological thresholds are approached. South Wales coal is the ancient remains of plants and animals alive in the Carboniferous Era, which was sequestered over millions of years underground under enormous pressure, over such long periods that the carbon comprising their structures was made into coal, oil, or natural gas During the heyday of the coalfield’s prosperity South Wales pointed the world towards fossil fuels as the dominant ecosystem service for boosting wellbeing. Exported through the port of Cardiff, Welsh coal supplied Homo sapiens world wide with energy to support its expanding culture of mass production with increased wealth to stimulate the purchase of its goods and services from afar.

By the 1850s, the people of South Wales was already consuming more natural resources than the valley’s could produce. Today we express this in terms of our ecological footprint being stamped on distant environments. Here is written a deeper message from the rise and fall of ‘King Coal’. It is a simple basic spiritual affirmation that we are all members of humanity and share a collective destiny beyond individual life. The morale of the solidarity of humankind echoes the ancient cross-cultural religious imperative to love one another. Within this cosmopolitan perspective, great possibilities for technological, social, and moral invention lie before us. But these are only possibilities, not predictabilities. The real is explicable and capable of change only in connection with the immensity of the possible. As we survey that immensity, we can allow ourselves hope but not optimism.

3 The Future

People of the Welsh valleys now face a global economy that is increasingly competitive. Key baseline indicators are new product innovation, broadband penetration, and educational attainment among younger generations. A competitive edge and a creative edge go hand-in-hand to support economic prosperity in today’s globalised economy. Business location decisions are influenced by factors such as the ready availability of a creative workforce and the quality of life available to employees. In this working environment a district’s arts and cultural resources can be assets that set a desirable context for economic development. The arts and heritage industries provide jobs, attract investments, and stimulate local economies through tourism, consumer purchases, and tax revenue. Perhaps more significantly, they also prepare workers to participate in the contemporary workforce, create communities with high appeal to residents, businesses, and tourists, and contribute to the economic success of other sectors. Creative economies depend in a variety of ways on the composition and character of businesses, nonprofit organisations, individuals, and venues that exist in any given area.

The creative economy may include human, organizational, and physical assets. It also includes many types of cultural institutions, artistic disciplines, and business pursuits. Industries that comprise the arts and culture sector may include advertising, architecture, the art and antiques market, crafts, design, fashion, film, digital media, television, radio, music, software and computer games, the performing arts, publishing, graphic arts, and cultural tourism. This is the present postindustrial multi-skilled condition for generating prosperity and wellbeing. It rests on what is called the ‘Foundational Economy’. This is the sheltered sector of the economy that supplies mundane but essential goods and services such as: infrastructures; utilities; food processing, retailing and distribution; and health, education and welfare. The foundational economy is unglamorous but important because is used by everyone regardless of income or social status, and practically is a major determinant of material welfare . The UK foundational economy employs around 35% of the working population; whereas current industrial policy focuses on manufacturing which employs just 8 per cent, of which the steel industry consists of only 1 per cent.

Most foundational activities involve branches and networks with some degree of natural monopoly reinforced by implicit or explicit state guarantees. The Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change suggests that the state should use this leverage to treat such activities as ‘social franchises’ and thereby increase the local benefits for the communities whose purchasing power sustains foundational activities. Under social franchises, large public and private foundational organisations would be obliged to offer social returns such as: supporting local communities and firms; living wages; sustainable supply chains; import substitution; and/or energy and resource sustainability.

However, the present could just as well open out upon a future of increasing instability resulting from a breakdown of standards and values or from a lack of purpose or ideals and frustration, of the breakdown of solidarity rather than its strengthening, of more ennui and envy and guilt rather than less. The growing awareness of scarcity may not lead to a more equitable distribution of resources but to an even more unjust one. This seems to be the situation in Wales which is languishing on the threshold of a new economy for life after coal..

Future history of consumerism is still being shaped, and all we know for certain is that the history of the consumer is entering a new phase. As explorers destined to set sail on uncharted seas of thought and action we should muster the courage to move in an unfamiliar direction reappraising values stemming from the foundation economy. Until now we moderns have assumed that the promised land of global social harmony lies in the direction of an ever-increasing standard of material well-being. Now we should try to sail toward the future on the opposite tack, in quest of a creative, shared austerity that will emphasize equity among humankind and harmony with nature. If we change our course and brave the unknown, we too may arrive on the banks of a new world where our demands on ecosystem services match the rate at which they can be produced without resort to fossil fuels, such as coal..

Mongolia, meanwhile, is advertising itself as “the Saudi Arabia of coal”. International mining companies have just started ripping off the tops of mountains to get at the world’s largest deposits of coking coal, most of which will go to feed the steel mills of China. What is happening in Mongolia dwarfs the cultural transformation of the South Wales valleys in its historical rush for coal. The profits from Mongolia’s superabundance of coal will propel a country of nomadic herders towards the living standards of the global middle class, tripling the size of its economy within a few years (Fig 4). The environmental effects are equally great. Huge opencast mines in the Gobi desert will increase water scarcity in an already arid zone; grasslands will parch under the clouds of dust thrown up by columns of lorries moving coal to the railheads; ancient ways of life will be lost. But, from a Mongolian perspective, these are minor consequences to live with when set against boosting the process of consumerism for the benefit of 2.6 million people.

Fig 4 The State department store: Ulaanbaatar

4 Internet extension materials

https://prinvest.uk/property-market/1704/a-modern-european-hub-5-reasons-to-invest-in-cardiff

http://www.culturalecology.info/halesworth/halesworth_html/index.htm