Art and mental modelling

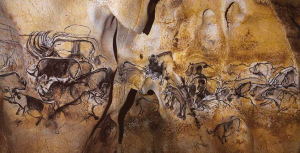

Lion Panel, Schuvet, Cave Painting

It is widely accepted in the cognitive sciences and literature that the human ecological niche is a self-constructed mental whole. That is to say, people develop and use their own internal representations, called ‘mental models’, to interact with the world. Making such personal mental models of cultural ecology underlies the process of enculturation. People must know about their environment so they can adopt appropriate behaviours to exist within it. Mental models are conceived of as a cognitive structure that form the basis of reasoning and decision making, particularly with respect to understanding the limitations to human survival. They are constructed by individuals based on their personal life experiences, perceptions, and understandings of the world. They provide the mechanism through which new information is filtered, stored and applied. From this point of view reality is provisional and dependent on what has been accepted into a person’s database through education and experience. The outcome of these adaptive behaviours is a distinct culture.

Current holistic mental models of the human ecological niche are rooted in the concept of ‘deep ecology’. This is a perception of reality that goes beyond the scientific framework defining the origins of species and their habitats to an intuitive awareness of the oneness of all life, the interdependence of its multiple manifestations and its cycles of change and transformation. Fritjof Capra says that when the concept of the human spirit is understood in this sense, the individual feels connected to the cosmos as a whole. It then becomes clear that ecological awareness is truly spiritual. Indeed the idea of the individual being linked seamlessly to the cosmos is expressed in the Latin root of the word religion, religare (to bind strongly), as well as the Sanskrit yoga, which means union.

To understand that Earth includes humanity as part of an interdependent spiritual whole is to see that there is no separation between the brain, the mind and the world. That which we commonly refer to as “self” is but a microcosmic aspect at the cellular edge of the vast complexity of our macrocosmic reality embedded in dark matter. Self awareness is the biological mechanism by which we equilibrate within the human ecological niche to survive. Here, in all our thoughts and actions, we are an integral part of nature and at one with its biophysical expressions in all that we do.

As a crucial outcome of human evolution we can glimpse the beginnings of ecological modelling in cave and rock art, where certain kinds of symbols regularly appear across time and space, although the peoples producing these recurring symbols had not been in contact with one another. These primeval symbols are not, in other words, the result of cultural diffusion. They are are a mixture of representative and abstract elements: Lewis-Williams calls them ‘entopic forms’

Entopic forms are records of the first mental models expressing the dependence of humans upon the rest of nature. But somehow along the course of time, the human mind in the cave became separated from this unified universal whole. There is now a cosmopolitan, scientific model of the human ecological niche where globalised consumerism is the reality of humanity dedicated to taking more from nature than its ecosystems can provide through regeneration and materials recycling.

But what is the role of art in ecological modelling ? According to the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, “Art is contemplation. It is the pleasure of the mind which searches into nature and which there divines the spirit of which Nature herself is animated“. What could Rodin mean?

At this point we can turn for a provisional answer to one of Rodin’s contemporaries. Jean Arp, also called Hans Arp, was a French sculptor, painter, collagist, printmaker and poet. The son of a German father and French Alsatian mother, he developed a cosmopolitan outlook from an early age and as a mature artist maintained close contact with the avant-garde throughout Europe. He was a pioneer of non-representative abstract art and one of the founders of Dada in Zurich, but he also participated actively in all important artistic movements of the time, particularly surrealism and constructivism.

Surrealism is an artistic, philosophical, intellectual and political movement that aimed to break down the boundaries of rationalization to access the imaginative subconscious. It is a descendent of Dadaism, which disregarded tradition and the use of conscious form in favour of the ridiculous. First gaining popularity in the 1920s and founded by Andre Breton, the approach relies on Freudian psychological concepts.

Proponents of surrealism believed that the subconscious was the best inspiration for art. They thought that the ideas and images within the subconscious mind were more “true” or “real” than the concepts or pictures the rational mind could create from observing nature. Under this philosophy, even the ridiculous had extreme value and could provide better insights into a culture or a person’s desires, likes or fears.

A major reason why many people took issue with the movement was because it abandoned conventional ideas about what made sense, what was ugly and what was art. In fact, much of what surrealism advocates was designed to break rules in overt ways. The art and writing of the time often holds images or ideas that, under traditional modes of thought, are disturbing, shocking or disruptive.

Constructivism is also a philosophy of mental modelling founded on the premise that, by reflecting on our experiences, we construct our own understanding of the world we live in. Each of us generates our own rules and mental models, which we use to make sense of our experiences. Learning, therefore, is simply the process of adjusting our models to accommodate new experiences. At the extremes constructivism defines truth as a provisional understanding.

Making biomorphs

Indian Ink, Hans Arp, 1944

In his art, Arp was more of a constructivist. Using black ink, watercolours and gouache he developed a distinctive graphical repertoire of abstract shapes for his sculptural reliefs. The same motifs, repeated from work to work in unique combinations, were intended as a kind of ‘object language’ of his neural activity. The forms he called biomorphs emerged spontaneously from his subconscious in response to taking up a paintbrush and art was the outcome of the brain’s nature. These biomorphs may have something in common with Lewis-Williams’ primeval entopic forms. While Arp prefigured junk art in his use of waste material, it was through his investigation of biomorphism and of chance and accident in artistic creativity that proved especially influential in later 20th-century art. Renunciation of artistic control and reliance on chance when creating his compositions reinforced the anarchic subversiveness inherent in Dada In this connection, he pioneered the use of chance in composing his images. For example, he haphazardly dropped roughly shaped squares onto a sheet of paper then glued them down and waited for his mind to make sense of the outcome.

With reference to Rodin, Arp’s stated aim was to avoid the traditional way that sculptors always started with natural forms and abstracted their desired shapes to exaggerate their character. Arp began with shapes emerging from his subconscious to make compositions with no reference to representing natural forms; his naming of the outcome only came when he contemplated his finished oeuvre.

“Dada is without sense, like nature. Dada is for nature against art. Dada is direct like nature. Dada is for infinite sense and for defined means”. This was the prelude to Arp’s verbal attack against two of the most celebrated works in the history of sculpture, the Venus of the Louvre and the Laocoon of the Vatican. Arp expresses what is probably his most specific contribution to Dada, as well as one of his personal constants: the denunciation of the anthropocentrism of man and his art. “Since the time of the cavemen, man has glorified himself, has made himself divine, and his monstrous vanity has caused human catastrophe. Art has collaborated in this false development. I find this conception of art which has sustained man’s vanity to be loathsome”.

Dadaists asked themselves if in changing art, it would not also be possible to change somewhat the behavior of man himself: “I wanted,” wrote Arp, “to find another order, another value for man in nature. He should no longer be the measure of all things, nor should everything be compared to him, but, on the contrary, all things, and man as well, should be like nature, without measure. I wanted to create new appearances, to extract new forms from man. This is made clear in my objects from 1917”.

By objects, Arp was referring to the biomorphs that had first surfaced in the graphic research he had initiated in 1917: “I drew with a brush and India ink broken branches, roots, grass, and stones which the lake had thrown up on the shore. Finally, I simplified these forms and united their essence in moving ovals, symbols of metamorphosis and of development of bodies”.

This period from 1917-20 was to mark a high point in Arp’s graphic work and to affirm the importance of black and white in his work. Commenting on this in 1955, he said: “I use very little red. I use blue, yellow, a little green, but especially, as you say, black, white and gray. There is a certain need in me for communication with human beings. Black and white is writing”. Thus, what should be seen in the ink drawings are calligraphies without sense, which nevertheless do not exclude communication. These signs, which hail us, are simple drawings; for example, three blots included over a hollowed-out blot, or black lines and forms highlighted with white.

Arp would not trouble himself if the randomness of the blots – and not the will of the person drawing them – would suggest to the imagination a key, dumbbells, a two-footed bottle, or anything that the viewer would be pleased to discern. Arp would not deprive himself, either, of inventing fantastic titles suggested by these forms. They were created automatically by movements of the hand and not by decisions of the intellect. To a critic he asked ‘What do you want?’ “It grows like the toenails on the feet. I have to cut them and they still grow.” This automatism, also manifests itself in the poems that Arp wrote simultaneously and that he would assemble in Die Wolkenpumpe (1920), or those he would compose with Tzara and Serner. The three composed in turn their roles on paper, without preconceived ideas, everything falling by chance from their pens, happily mixing languages.

Creativity as mental self-organisation

According to Arp, drawing, sculpture and poetry should originate in themselves through a process of automatic self-organisation; for him, this was a fundamental principle: “I allow myself to be guided by the work which is in the process of being born, I have confidence in it. I do not think about it. The forms arrive pleasant, or strange, hostile, inexplicable, mute, or drowsy. They are born from themselves. It seems to me as if all I do is move my hands”. He was in favour of the dream: “Genesis, birth and eclosion often take place in a daydreaming state, and it is only later that the true sense of these considerations becomes apparent”. From the first abstract creations a viewer faced with an inexplicable painted canvas would cry out in exasperation, “Why! an infant child could produce this”. From the point of view of Arp’s spontaneously produced biomorphs the viewer is right.

The process of creation was always the same for Arp. Form comes first, then meaning. That is why he never knew a priori what the title of a work in progress was to be: “Each one of these bodies certainly signifies something, but it is only once there is nothing left for me to change that I begin to look for its meaning, that I give it a name”. If a work was entitled ‘Branches and Spectres Dancing’, or ‘Drawer Head’, or ‘Banner- Wheel’, it was not because the artist intentionally deformed existing objects, but rather that the forms born naturally from brain to hand suggest such an association of ideas or the objects they resemble. If no association came to him, he would call it simply ‘Drawing’, ‘India ink’, ‘Collage’, or ‘Composition’.

Space for the mind

We each live in a tiny little corner of reality where we perpetually insist on carving out a space for our ego. In this mental portion of our ecological niche we can experience the interconnected, mutually dependent facets of our neural processes as they seek to find balance and harmony with the environment. Just as the natural harmony of the planet is dependent on all of its parts working together in a felicitous and balanced manner, a mind in union with its environment functions socially when it acts in harmony with its self and the body that contains it.

In the last chapter of his biography of Hans Arp, Serge Fauchereau refers to a book, ‘Jours effeuilles’, which was published as a foreword to an exhibition Arp was doing with his friend Richter in 1966, the year of his death. Arp states: “To be full of joy when looking at an oeuvre is not a little thing”.

Fauchereau commented “In a time as dominated by confusion as our own, and which privileges the pathetic in art and life, the tragic or the sarcastic and the grimacing, a case in which calm joy – a joy produced while regarding one’s own oeuvre – is not to be taken lightly. Artists like Arp, after all, do not come along that frequently”.

It is entirely up to the viewer to discern the content and meaning of what is painted. The message or emotion is in the eye of the beholder, not the eye of the creator. The artist’s creativity is in drawing out an emotion or an interpretation from the viewer. If this interpretation differs from what was intended by the artist (if indeed anything he intended anything), this in no way invalidates the interpretation placed on the work by any individual viewer.

Arp begat non-representational abstraction, which has become a global way of thinking and seeing. It runs alongside representational art and together both kinds of art are tools that express cultural identity locally and globally. Non-representational, abstract art is an expression of cosmopolitanism because artists shift the emphasis of artmaking away from individual objects or happenings representing ethnic cultural identity towards a form of expression that is within the capability of the whole of humanity. In this sense, art unifies humanity, as Rodin believed, through contemplating the pleasure of the mind. It can also carry messages between peoples through the responses of the maker and viewer to the images.

Non-representational abstraction can be regarded as composed of three main processes; (i) the brain’s effort to analyze the pictorial content and style; (ii) the flood of associations evoked by it; and (iii) the emotional response it generates. Being of no practical use, art in general enables the viewer to exercise a certain detachment from “reality”. Arp was the first to define non-representational abstract art as part of a special maker/viewer cognition system where the maker’s interpretation of what she has made comes after the work is finished. The visual stimulus in the brain of the viewer is not object-related. Therefore the automatic object recognition systems in the brain are not activated by abstract art. The viewer has to form new “object-free” associations from more rudimental visual features such as lines, colors and simple shapes. This conclusion is supported by the lack of specific regions in the brain for processing abstract art exclusively. Also, eye tracking experiments, demonstrate that in abstract art, the brain is “free” to scan the whole surface of the painting rather than picking out well recognized salient features, as is the case when processing representational art.

Abstract art may therefore encourage the brain to respond in a less restrictive and stereotypical manner, exploring new associations, activating alternative paths for emotions, and forming new possibly creative links. It also enables us to access early visual processes dealing with simple features like dots, lines and simple objects that are otherwise harder to access when a whole “gestalt” image is analyzed, as is the case with representational art. Surely, this is what Rodin meant when he used the term ‘animation of nature’. If abstract art is the key to the animation of nature it may also be the key to promoting the Dadaists educational objective that was to change ‘the behavior of man himself’.

Feeling is a Fragile Container, Qiu Zhenzhong, 2005

References

https://www.maps.org/news-letters/v19n1/v19n1-pg61.pdf

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss1/art46/

Arp, Serge Fauchereau, Ediciones Poligrafa, SA, 1988

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3937809/

http://www.pearllam.com/exhibition/beyond-black-and-white-chinese-contemporary-abstract-ink/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3937809/

http://genealogyreligion.net/entoptics-or-doodles-children-of-the-cave