In his Easter message for 2015, John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, seeking ways to satisfy people’s yearning for a more idealistic society, envisaged a better and greater social reality where we can afford to be magnanimous, putting ourselves second, and placing other people’s needs on a par with our own. His standpoint is that people,

“….know in their bones that there must be something better, something more worthwhile than the self-centredness which is attracted by the promise of endless pleasure, but which somehow never seems to materialise.”

He says that it can’t be right for consumerism (which we used to call greed) to measure the worth of human beings by what they own, what they eat and how up to date with fashion they are. Regarding the search of young people for something better, the Archbishop sees a danger that yearning for something more idealistic can be misdirected. This he exemplified by referring to how some teenagers have been seduced by the promise of the false utopia of the Islamic State or even martyrdom to that cause, which would have us roll back a thousand years of human progress.

Prince Charles confessed his perplexity at this development in these words:

“The radicalisation of people in Britain is a great worry, and the extent to which this is happening is alarming, particularly in a country like ours where we hold values dear. You would think that the people who have come here, or are born here, and who go to school here, would abide by those values and outlooks. I can see some of this radicalisation is a search for adventure and excitement at a particular age.”

David Cameron, as Prime Minister, was one of those who tried and failed to fulfil a grander vision with his notion of the ‘Big Society’. Similarly, Gordon Brown, when he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, attempted to define British values as a focus for creating an all inclusive national identity as a platform for empowering citizens to control their own lives , but little came of it.

In 2007, Brown introduced this unifying idea of citizen empowerment by developing the theme of Britain’s ‘golden thread of liberty’. His starting point was that national identity has become far more more of a debating point with two thirds now identifying Britishness as important, and recent surveys show that British people feel more patriotic about their country than almost any other European country. One reason for this, Brown believes is that Britain has a unique history – and what has emerged from the long tidal flows of British history – from the 2,000 years of successive waves of invasion, immigration, assimilation and trading partnerships, from the uniquely rich, open and outward looking culture. It is this which has produced a distinctive set of British values which influence British institutions.

This prompted Brown to identify the golden thread which runs through British history;

“…. that runs from that long-ago day in Runnymede in 1215 when arbitrary power was fully challenged with the Magna Carta, on to the first bill of rights in 1689 where Britain became the first country where parliament asserted power over the king, to the democratic reform acts – throughout the individual standing firm against tyranny and then – an even more generous, expansive view of liberty – the idea of all government accountable to the people, evolving into the exciting idea of empowering citizens to control their own lives”.

Woven also into that golden thread of liberty are countless strands of common, continuing endeavour in our villages, towns and cities – the efforts and popular achievements of ordinary men and women, with one sentiment in common – a strong sense of duty; the Britain of local pride, civic duty, civic society and the public realm. The Britain of thousands of charities, voluntary associations, craft societies but also of churches and faith groups. Britain’s history tells us that worthwhile values are not vague aspirations, but hard won and enduring moral and ethical principles which shape national policies and personal behaviour.

For Archbishop Sentamu the origin of the United Kingdom’s moral direction is grounded in the Bible. It has its roots in the Old Testament and came to fruition in Christianity, where it is exemplified in the following words of Jesus:

“Everyone who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice is like a wise man who built his house on the rock. The rain came down, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat against that house; yet it did not fall, because it had its foundation on the rock. But everyone who hears these words of mine and does not put them into practice is like a foolish man who built his house on sand. The rain came down, the streams rose, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell with a great crash.”

Cameron also referred to Biblical values as important features of a big society when he says: “There are those millions who keep on strengthening our society – being good neighbours, running clubs and voluntary associations, playing their part in countless small ways to help build what I call the big society”.

“Many of these people are Christians who live out to the letter that verse in Acts, that ‘it is more blessed to give than to receive’. These people put their faith into action and we can all be grateful for what they do.”

Cameron was referring to the Acts of the Apostles, the fifth book of the New Testament, in which the Apostle Paul quotes Jesus as he addresses the Ephesian elders. Paul says in the King James Version in Acts 20:35:

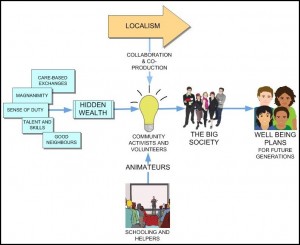

On the other hand, Edgar Kahn, the author of “No more throw away people”, takes the secular stance, that we have the financial economy and the core economy. The latter is the talent and skills that we all uniquely possess and can excel at. If society can value these core skills, and enable their use, then we can empower people whose worth is often measured only in terms of financial capacity. Kahn applies the notion of time banking to activate localism through collaboration and co-production as central to values of sustainable development.

In line with Kahn’s notion of the ‘core economy’, David Halpern defines ‘hidden wealth’ as the value of our care-based exchanges, which are grounded in social norms of cooperation and trust. Compared to the relatively nebulous notion of the Big Society, which is an outcome of activating communities for voluntary action, Kahn’s ‘core economy’ and Halpern’s ‘hidden wealth’ are empirically grounded resources, and strong drivers of economic growth and national wellbeing that would appeal to believers and non-believers alike. They both fall within the definition of natural economy, which refers to a type of economy where money is not used in the transfer of resources among people. It is a system of allocating resources through direct bartering, entitlement by law, or sharing out according to traditional custom. As such it is a basic pillar of the human ecological niche and the essence of localism. In this context, localism describes a range of political philosophies which prioritize action generated in the local community.

Generally, localism supports local production and consumption of goods, local control of government, and promotion of local history, local culture and local identity. Localism can be contrasted with regionalism and centralised government, with its opposite being found in the unitary state. Sentamu, Cameron, Brown, Kahn and Halpern all believe we are made for a greater reality where the aim is to create a climate that empowers local people and communities, building an inclusive society that would take power away from politicians and give it to people, and all of them are seeking a practical agenda to meet this objective. These ideas stress the importance of connecting with the people around us and demonstrate how investing time in building these relationships will enrich our lives. They illustrate how being active and discovering the importance of physical activity that we enjoy, clearly enhances health and well-being and they go on to encourage curiosity through taking notice of the extraordinary things in our day-to-day lives, urging us to be more aware of the world around us and what we are feeling, and learning to reflect on this. Crucially they emphasize the importance of learning and taking on new challenges, to improve self-confidence.

Finally they stress the importance of giving and seeing ourselves in relationship to the wider community; being a part of civic society that has a global reach. In other words, cultural change only becomes meaningful when we alter our relationship not just to the state, but to each other and ourselves. Whatever else we think of their ideas, their credibility is based on inclusivity and metropolitanism. They hinge on the viability of the demands placed on ‘people’ to participate and cooperate for a common purpose. These demands will be particularly acute, as will the kinds of assumed competencies that are implicit in these demands.

Regarding the implementation of the ideas surrounding the concept of Big Society, the Royal Society of Art’s Social Brain project, ‘The Hidden Curriculum of the Big Society’, argues that instead of framing the Big Society as an implausible technical (policy-driven) solution to socio-economic challenges, it can only work as an adaptive (personal and cultural) challenge to utilise and build our hidden wealth. Curriculum literally means to ‘run the course’, as in curriculum vitae, the course of an individual’s life. The ‘curriculum’ of the Big Society is viewed as a long term process of cultural change, consisting of the myriad activities and behaviours that people are explicitly being asked to participate in and subscribe to. The hidden curriculum of this process of cultural change comprises the attitudes, values and competencies that are required for this process.

The main purpose of RSA report is ‘to highlight the nature of this hidden curriculum, and indicate how it might inform policy and practice, particularly in relation to releasing hidden social wealth and increasing social productivity’. Understood in this way, the curriculum of the Big Society, including mass participation and cooperation, seems to require us to gain certain key competencies that are involved in social productivity and cooperation, including responsibility, autonomy and solidarity. The report argues that acquiring these competencies is not straightforward and entails significant developmental challenges, amounting to a hidden curriculum for a growth in mental complexity on a national scale. Therefore, to make the Big Society message bolder and clearer, we need to be more insightful about the emotional and psychological demands and rewards of participation.

For the Big Society to work, we need to support adult development. Government programmes to prevent the radicalisation of young Muslims will be ineffective if all they can offer as an alternative is the status quo. In the eyes of most young people, the status quo has been tried and found wanting. Something far more worthwhile and exciting is needed. The big idea common to the ‘idealistic society’, ‘the big society’, ‘the core economy’, ‘the hidden economy, and ‘the natural economy’ is the need to make more of our ‘hidden wealth’- the human relationships that drive and sustain the forms of participation needed to make society more productive and at ease with itself. But this needs in turn a fundamental change in people’s attitudes. Available evidence suggests the level of mental agility required to develop the competencies required to make societies hidden wealth available is not currently widespread in the adult population. So for these ideas to take root, we need to invest more time and energy making sure that the forms of participation and engagement called for are supported by formal and informal adult education. Social productivity requires that people are both supported, challenged and led by local activists. Realising our hidden wealth rests on the re-engagement of people as “active citizens”, enabled to take informed decisions about their lives, communities and workplaces but also to be more participative in designing and in providing services that are demand driven from grass roots.

However, many people are both disengaged and lack the confidence, skills, knowledge or understanding to do so. This is particularly true for people with little formal education and those most at risk of social exclusion. But even among educated and informed citizens, who perceive advantages in participating more in grass roots initiatives to protect their, and their communities interests, there are few who are prepared to devote the time and energy on a sustained basis to participate in community driven initiatives. This is even more so, if there is a lack of available funding. And, of course, many will be expected to act on a pro bono basis. It is also the case that there have been too few examples presented of what a big society looks like in practice.

There is an obvious role for local authorities. For example, local authority service boards are central to the workings of the Welsh Government’s ‘Future Generations Bill, which requires all the boards establish local wellbeing plans to meet the challenges and opportunities to reconceptualizing grassroots activism. The objective is to establish a role for community-based organizations in advancing local well-being, in particular through education and social inclusion strategies. But the very bodies – local authorities – that might kick start the initiative, apart from feeling the financial squeeze , remain , for the most part, unsure of what the big society thinking means for them and its practical implications for their commissioning and procurement of local services. There is another education gap to be plugged!

http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/grassroots_08022012.pdf http://www.artsforhealth.org/resources/Big_Society_Arts_Health_Wellbeing.pdf