“I believe when people call themselves spiritual they are basically signaling three things: first, that they believe there is more to the world than meets the eye, that is to say, more than the mere material. Second, that they try to attend to their inner life — to their mental and emotional states — in the hopes of gaining a certain kind of self-knowledge. Third, that they value the following virtues: being compassionate, empathetic and open-hearted.”

http://theconversation.com/what-does-it-mean-to-be-spiritual-87236

1 Cultural ecologies

The term oekologie was coined in 1866 by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel. The word is derived from the Greek οικος (oikos, “household”) and λόγος (logos, “study”); therefore the original definition of “ecology” means the “study of the household [of nature]”

Ecology originally referred to the interrelationships between living creatures and their habitats, but over the years the term has been generalised to mean the set of relationships existing between any complex system and its surroundings (Table 1).

Table 1 Ecologies of species and works of art

| Features | Environment | Influences |

| Species | Habitats | Biophysical factors |

| Works of art | Societies | Beliefs and ideas |

Space-time is a mathematical model of the universe that joins space and time into a single idea called a continuum. This four-dimensional continuum is known as Minkowski space. Combining these two ideas helped cosmologists to understand how the universe works as an ecology on the big level (e.g. galaxies) and small level (e.g. atoms). For the convenience of education the dynamic continuum of the universe, when focused on Homo sapiens and planet Earth, has been divided into five ecologies of habitats, species, culture, politics, and economics. These are broad, well defined bodies of knowledge which are connected through interdisciplinary issues. They are best studied by applying ecological systems thinking to life on Earth, where the old subdivisions of knowledge give too narrow a perspective for tackling the problems of human life on an overcrowded planet.

Cultural ecology is the study of the distribution and abundance of people and the interactions between them and their biophysical environment. A cultural ecosystem defines a particular biophysical environment and its human inhabitants functioning together as a society. This occurs with respect to the expression of its ideas, customs, and social behaviour in a habitat associated with a particular community of plants and animals.

In every culture in the world, artistic expression has emerged to provide an outlet for thoughts, feelings, traditions, and beliefs. Art can be both rooted in history and a catalyst for change in a culture. Many works of art are rooted in religion. From these points of view cultural ecosystems may be defined by the dynamics of the interactions between particular styles of art and the society in which they were created. The outcome is to picture the essence of the universe and our place in it.

Albert Einstein remarked that the eternal mystery of the world is its intelligibility. Religion fastens on to this element to create a system of thought and action. The connections between religion, which answers the question, who we are, and science which answers the question, how we are, come together in art.

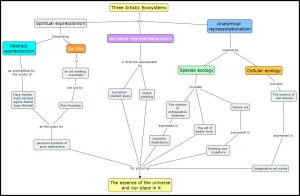

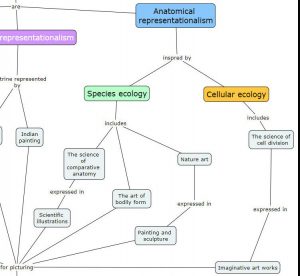

These ecologies and their ecosystems all promote the use of concept maps and mind maps as aids to comprehension of the whole. This type of mapping system begins with a main idea or subject that then branches out to show how it can be broken down into specific topics with connections between them (Fig 1).

Fig 1.1 Concept map of three ‘art in science ecosystems’ that depict a spiritual essence of the universe and our place in it.

https://cmapscloud.ihmc.us:443/rid=1SXPGYKQV-774H99-TPTNF

Cultural ecology includes the study of cultural ecosystems that define the flow of ideas and and their expression. In this connection, a growing number of contemporary scientists use the arts in a practical way to assist in their research, to gain insights that feed into their research, or to communicate their research to the general public. This notion of research as art differs from traditional scholarship in that it is not characteristically beholden to disciplinary conventions and parameters, and may present “findings” in visually aesthetic formats or those otherwise atypical of academic or journalistic publications.

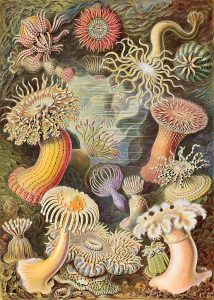

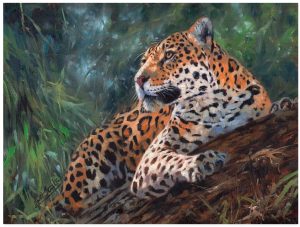

Within cultural ecology, ecosystems of art and ideas are based on the model of consciousness, or “mind ”, as being like an ecosystem, and ideas as being like the flora and fauna of this system. Like the plants and animals in a tangible ecosystem, ideas are then subject to evolution, extinction, or successful flourishing. In biological ecology, scientists strive to understand biological processes so that we promote those we deem beneficial and avoid introducing destructive elements into the system. Taking this point of view we define conservation management systems that match our use of ecosystem services to the rate of production of the natural resources they are capable of delivering.In the world of nature conservation the connection between art and nature is central to the understanding of each. Before the widespread use of photography, much of what we refer to as the visual arts involved an attempt to picture the the natural world in all its biodiversity of species. Thus, throughout history, visual artists have been inspired to capture the complex as well as the sublime qualities of nature and its life-forms. Scientists have done the same via observational recording, classification, counting, and analysis.

2 Spiritual expressionism

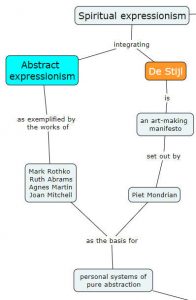

Fig 2.1 Concept map of spiritual expressionism

At its most basic, spiritual expressionism states that the fundamental, definitive quality of art is the ability to capture some aspect of spiritual thinking. The goal of spiritual expressionism is to find ways of representing divinity. It is an ideology, such as the expressive theory, which sees the fundamental role of art as the expression of emotion.

The relationship between art and spirituality has been historically mediated through the relationship between art and religion. As we have seen, this is particularly evident in the art of India. In Western art history prior to the 20th century, spirituality was often subsumed by religion. While the origins of stained glass are unknown, the Gothic period of architecture saw a blossoming in the use of stained glass in its great cathedrals. In addition to artistic practicality, glass craftsmen found the mysterious qualities of glass exemplary to represent the religious and spiritual ideologies of the period, which they steadily honed to a fine art.

The relationship between art and religion was fractious; at times they were mutually reinforcing, while at others there was dissension because of the lack of unanimity about the image. The crux of the Iconoclastic controversies of the 8th and 9th centuries, and later the Protestant Reformation, was not so much a denial of the importance of imagery but, on the contrary, was about just how much power images held. The iconoclasts believed that the use of images distracted from the main goals of religious practice, and could lead to moral and religious corruption. But in spite of the decline of organized religion in Western Europe, there has been growing interest in spirituality in areas of cultural life, especially in art. Many people no longer view institutionalized religion, as adequate for exploring their spirituality and look to new forms of spirituality as alternatives for finding ultimate meaning and addressing the profound needs of humanity. Central to the role of the artist has been a preoccupation with the deeper questions of life, often to reveal sights that are normally kept hidden from the public gaze and to challenge entrenched beliefs. The process of creating art is often described in quasi-mystical terms, whereby the artist-as-shaman unleashes or channels special creative powers in a process of making. This transports the viewer to a different realm of the imaginary. Given these affinities between the roles of art and spirituality, it is unsurprising that spirituality is an enduring feature of contemporary art. Key written works, particularly Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) and Der Blaue Reiter Almanac(1912), defended abstract art and revealed how non-objective forms could evoke the inexpressible through engagement with its formal qualities. In his 1911 work, Kandinsky emphasized his staunch belief in the redemptive qualities of the spiritual. He envisioned the Kingdom of God as an artistic domain that could be accessed by the artist-as-prophet, who was able to traverse “[t]he nightmare of materialism”to attain spiritual utopia through art. Abstract art provided the necessary means to do this, and the belief presented was that “[t]he more abstract [its] form, the more clear and direct is its appeal. Since Kandinski experiences of the spiritual have often been sought outside of the traditional themes of religious narratives and imagery, which have often been presented in veiled or coded language. In this respect, it could be said that religious expressionism is an offshoot of abstract expressionism exemplified by the works of William de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Ruth Abrams, Agnes Martin and Joan Mitchell.

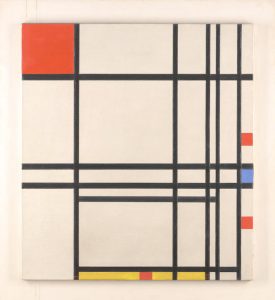

De Stijl was a circle of Dutch abstract artists who promoted a style of art based on a strict geometry of horizontals and verticals. Originally a publication, De Stijl was founded in 1917 by two pioneers of abstract art, Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. De Stijl means style in Dutch. The magazine De Stijl became a vehicle for Mondrian’s ideas on art, and in a series of articles in the first year’s issues he defined his aims and used, perhaps for the first time, the term neo-plasticism. This became the name for the type of abstract art he and the De Stijl circle practised. As a manifesto it took…..

- from cubism: the reduction of form to geometric elements (note that this was not the goal of cubism but it was how Mondrian and the de Stijl artists chose to understand and use it)

- from art nouveau and symbolism: the flat, mural quality of paintings and design with emphasis on the surface;

- from Van der Leck: a desire for an objective language of art

- from Kandinsky and theosophy: a relationship of spirituality to abstract form

- from philosophy: the belief that forms and colour can express “liberation” of the spirit; art should move and would move away from sensuality and materiality towards spirituality (this is also the influence of Kandinsky)

- from mysticism: the belief that numbers can express purity; the belief that the outcome precedes actuality in a conceptual manner; the conceptualization leads to style and style becomes reality; in addition to this belief, revelation is central to mystical philosophy: this mean that the spiritual and philosophical act of contemplation allows the subsequent recognition of reality in a form which is consistent with the goals of mysticism.

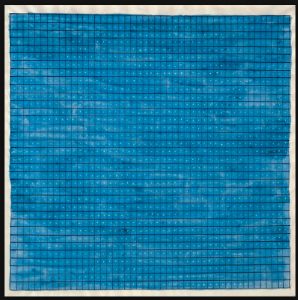

The grid is a visual structure that Mondrian conjured as his interpretation of De Stijl and placed at the roots of contemporary art. As a graphic component in painting, it came to prominence in the early 20th century when Mondrian was widely considered the “most modern” artist of his time. In 1912, he began to create his “compositions,” paintings based on grids of horizontal and vertical black lines in three primary colours. “These basic forms of beauty,” he wrote, “supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true.” In fact curves are totally absent from his works.

The art historian Rosalind Krauss has pointed to the emergence of the grid as a critical step in the evolution of modern art. In her 1979 essay “Grids,” she wrote:

“In the early part of this century, there began to appear, first in France and then in Russia and in Holland, a structure that has remained emblematic of the modernist ambition within the visual arts ever since. Surfacing in pre-War cubist painting and subsequently becoming ever more stringent and manifest, the grid announces, among other things, modern art’s will to silence, its hostility to literature, to narrative, to discourse.”

The painting named ‘Abstraction’ (Fig 2.2) is one of the culminating paintings that Mondrian had developed by 1921 consisting of straight horizontal and vertical lines, rectangular shapes resulting from their crossing; and a palette of black, white, and the primary colours. He wrote: “Observing sea, sky, and stars, I sought to indicate their plastic function through a multiplicity of crossing verticals and horizontals. . . .

Fig 2.2 Abstraction: Piet Mondrian, 1921

8-1-12_Mondrian_AP1994_05, 8/1/12, 11:38 AM, 16C, 6726×8169 (732+1572), 100%, Custom, 1/8 s, R42.7, G17.1, B30.4

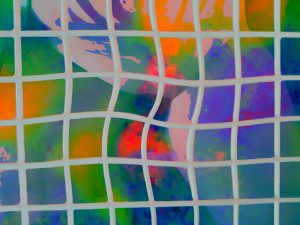

Like Mondrian, but twenty years after his death, the abstract expressionist, Agnes Martin, used the grid to organize a personal perception of nature into her canvases that were awash with colour, thus seamlessly blending what on the surface are two very different art styles: ‘minimalism’ and ‘colour Field’ (Fig 2.3).

Martin’s works are non-representational, yet the titles of her paintings and her own words about her art and life indicate that she was strongly influenced by nature – a focus that brought together different areas of her life. Her adherence to Buddhism encouraged her to rely on her everyday surroundings for subject matter; and her schizophrenia meant that she did not relate well or easily to humans, so that nature represented a calm, ordered refuge.

Martin’s use of the grid along with her focus on non-representation released the artist from the burden of traditional subject matter while allowing her to explore infinite variations of subtle colour. The resulting freedom of her artwork was at odds with the monastic restraint of her daily life.

About her work she says: “When I think of art I think of beauty. Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not in the eye it is in the mind. In our minds there is awareness of perfection.”

Fig 2.3 “Summer” (1964): Synthesizing both Abstract Expressionism and minimalism. Agnes Martin

Martin’s work is has been likened to an archetype of aspects of pioneering America: the quietism of the Quakers, the spare and well-made furniture of the Shakers, the transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the nature worship of Henry Thoreau, to which, in the 1930s, she added a deep interest in Zen Buddhism and other eastern philosophies long before these became almost mandatory among artists.

Writing about her works she said:

“My paintings have neither object nor space nor line nor anything — no forms. They are light, lightness, about merging, about formlessness, breaking down form. You wouldn’t think of form by the ocean. You can go in if you don’t encounter anything. A world without objects, without interruption, making a work without interruption or obstacle. It is to accept the necessity of the simple direct going into a field of vision as you would cross an empty beach to look at the ocean.”

Martin praised the colourfield painter Mark Rothko for having “reached zero so that nothing could stand in the way of truth”. Following his example Martin also pared her works down to the most reductive elements to encourage a perception of perfection and to emphasize transcendent reality. Her signature style was defined by an emphasis upon line, grids, and fields of extremely subtle colour. Particularly in her breakthrough years of the early 1960s, she created 6 × 6 foot square canvases that were covered in dense, minute and softly delineated graphite grids In the 1966 exhibition Systemic Painting at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Martin’s grids were therefore celebrated as examples of Minimalist art and were hung among works by artists including Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman, and Donald Judd. While minimalist in form, however, these paintings were quite different in spirit from those of her other minimalist counterparts, retaining small flaws and unmistakable traces of the artist’s hand; she shied away from intellectualism, favouring the personal and spiritual. Her paintings, statements, and influential writings often reflected an interest in Eastern philosophy, especially Taoist. Because of her work’s added spiritual dimension, which became more and more dominant after 1967, she preferred to be classified as an abstract expressionist. A better description would be to describe her as a spiritual expressionist. This concept is developed further in the linked Tumblr blog.

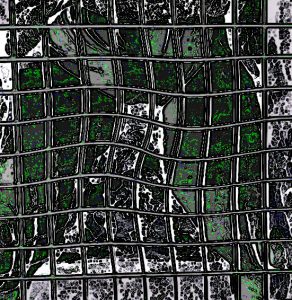

One of the central conventions of Western art is the idea that the painted canvas can be viewed as a window onto the world; that the existence of a flat surface is concealed and the painting presents the illusion of real life. On the other hand, the philosophy of Mondrian places the grid grid as an emblem of modernism and modern artists have created works that reassert the presence of the flat canvas or play with the idea of the penetrable or illusory nature of that surface. In some works there is a deliberate formal oscillation between flatness and three-dimensional space. Therefore the grid has become a key device in the understanding of the canvas as both a window and a flat surface. To some, the grid suggests the division of a window into panes of glass through which the world beyond can be seen, whilst simultaneously reminding the viewer of the presence of the two-dimensional surface they are viewing (Figs 2.4-5).

Fig 2.4 Bent grid 1,Corixus, 2018

Fig 2.5 Bent grid 2, Corixus, 2018

http://corixus.tumblr.com/post/179241914683/spiritual-expressionism

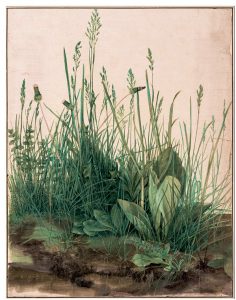

Spiritual expressionism is summed up by the work of Joan Mitchell, who, defining abstract art, said:

“Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work. This is just a use of space and form: it’s an ambivalence of forms and space.”

“My paintings are titled after they are finished. I paint from remembered landscapes that I carry with me – and remembered feelings of them, which of course become transformed. I could certainly never mirror nature. I would more like to paint what it leaves with me.”

Joan Mitchell is known for the compositional rhythms, bold coloration, and sweeping gestural brushstrokes of her large and often multi-panelled paintings. Inspired by landscape, nature, and poetry, her intent was not to create a recognizable image, but to convey emotions. Mitchell’s early success in the 1950s was striking at a time when few women artists were recognized. She referred to herself as the “last Abstract Expressionist,” and she continued to create abstract paintings until her death in 1992. Inspired by the gestural painting of Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline, Joan Mitchell’s mature work comprised a highly abstract, richly coloured, calligraphic manner, which balanced elements of structured composition with a mood of wild improvisation.

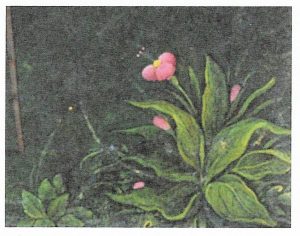

Mitchell rejected the emphasis on flatness and the “all-over” approach to composition that were prevalent among many of the leading Abstract Expressionists. Instead, she preferred to retain a more traditional sense of figure and ground in her pictures, and she often composed them in ways that evoked impressions of landscape (Fig 2.6).

Fig 2.6 Little weeds, Joan Mitchell

http://www.harley.com/art/abstract-art/index.html

This correspondence between the arts issued largely from Symbolism and had been inspired by scientific studies of colours and tones as sensations. The ‘pure’ abstract painters – Vasily Kandinsky, Frank Kupka, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich – who followed after 1910, however, always declared that their paintings were not music, nor that they were painting music. Rather, they claimed that painting’s tonal colours have an effect on the human being just as music’s tones do: the relationship between music and painting is a parallel one, colour and tone affecting and enlivening human feelings

Tone in painting and drawing refers to the light and dark values used to render a realistic object, or to create an abstract composition. When using pastel, an artist may often use a colored paper support, using areas of pigment to define lights and darks, while leaving the bare support to show through as the mid-tone. Tone can also mean the colour itself. One colour can have an almost infinite number of different tones. In this connection, tonal painting involves harmonizing or unifying a limited range of colour calling upon a whole range of tones within the limited colours to produce what is termed the atmosphere of the work. For example,in Wistler’s painting (Fig 2.7) of August 1871. This is the first of Whistler’s Nocturnes. In this work Whistler concentrated on the tonal qualities of blue and grey, aimed to convey a sense of the beauty and tranquillity of the Thames by night. It was Frederick Leyland who first used the name ‘nocturne’ to describe Whistler’s moonlit scenes. It aptly suggests the notion of a night scene, but with abstract musical associations. The name nocturne was first applied to musical compositions in the 18th century, when it indicated an ensemble piece in several movements, normally played for an evening party and then laid aside. The expression was quickly adopted by Whistler, who later explained,

By using the word ‘nocturne ‘ I wished to indicate an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest which might have been otherwise attached to it. A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form and colour first’.

In other words, his tonal pictures were to be perceived as abstract creations akin to musical compositions.

Fig 2.7 Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, 1871.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea 1871 James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834-1903 Bequeathed by Miss Rachel and Miss Jean Alexander 1972 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01571

Instrumental music is fundamentally abstract because it represents emotional states, symmetry and repetition, and other intangibles. A common purpose of both abstract art and instrumental music as communication systems is to allow maker, and receiver indirect access to their inner feelings. Abstract art and music afford a way to get in touch with the unconscious part of our existence, even if we don’t realize what is really happening. In this sense, the role of the maker of non representational art is to create a vehicle for communication that, when viewed or heard by another, evokes subconscious feelings and emotions.

In a musical art form tone colour is the characteristic that allows us to distinguish the sound of one instrument from another. Every instrument produces its own tone colour. For example, when you hear a clarinet and a guitar play the exact same pitch, the tone colour of each instrument allows you to tell the difference between the sounds that you hear. Furthermore, two violins are likely to emit different tone colours. Another name for tone colour is timbre. We often use terms like warm, dark, bright, or buzzy to describe musical tone colour.

The reason music and abstract painting have the potential to be so powerful in arousing an emotional response is that they keep the conscious meaningful distractions to a minimum, so virtually all brain power is devoted to feelings. As a partaker, you can open yourself, let in the energy and spirit that the maker put into the work, and allow it to interact with an open-minded brain.

The difference between the two art forms comes with their ‘reading’. A musical message is presented n a fixed, linear fashion, progressively following the composer’s score from beginning to end. In abstract painting there is no fixed route for all to follow; the eye searches for meaning in an idiosyncratic way.

3 Narrative representationalism

Fig 3.1 Concept map of narrative representationalism

In philosophy representationalism is the doctrine that in perceptions of objects what is before the mind is not the object but a representation of it. In art representationalism is the practice or principle of representing or depicting an object in a recognizable manner,especially the portrayal of the surface characteristics of an object as they appear to the eye.

http://corixus.tumblr.com/post/179178592353/extracting-a-pa%C3%ACntings-riches

Narrative representationalism tells a story. It uses the power of the visual image to ignite imaginations, evoke emotions and capture universal cultural truths and aspirations. What distinguishes narrative representationalism from other genres is its ability to narrate a story across diverse cultures, preserving it for future generations.

As far as we can tell painting was integral with the first appearances of storytellers, bards, prophets and poets, who were called upon to tell their visions. Ťhrough a live encounter, they provided verbal images that could direct, entertain, provoke, heal and reconcile the communities in which they worked. Storytellers say that any story that they craft will in turn craft them to be a fit instrument for its telling. We are, in fact, made of stories, some of which serve our individual and collective endeavours, others binding us to outmoded images. Imagination, therefore, is the key to the invisible realm from which all stories and everything new and possible can be born. Coupled with clear intention, this essential human faculty will help connect people to those creative forces which are ever available to them. The future is shaped, for good or ill, by the stories we believe and follow

While telling almost any story involves words, characters and structure, making a picture of a story involves another aspect of storytelling the use of visual language. Visual language refers to how imagery is used to convey story ideas or meanings. Perspective, colour, and shape can all be used to support a story by guiding the audience to see,feel and dream certain things.

What we have in our minds in a waking state and what we imagine in dreams is very much of the same nature. Dream images might be with or without spoken words, other sounds or colours. In the waking state there is usually, in the foreground, the buzz of immediate perception, feeling, mood, as well as fleeting memory images. In a mental state between dreaming and being fully awake is a state known as ‘day dreaming’. This is a meditative state, during which the things we see in the sky when the clouds are drifting, the centaurs and stags, antelopes and wolves, are projected from the imagination.

Abstract art has shown that the qualities of line and shape, proportion and colour convey meaning directly without the use of words or pictorial representation. Wassily Kandinsky] showed how drawn lines and marks can be expressive without any association with a representational image. From the most ancient cultures and throughout history visual language has been used to encode meaning:

“The Bronze Age Badger Stone on Ilkley Moor stands over a metre high and around 3 metres in length. This bolder has a southwest facing flattest surface that is marked with a profusion of cups, rings, interlinking grooves and gutters. Depending on the weather and sunlight the rock can change from grey and featureless to a rich golden brown, resembling a miniature Uluru/Ayers Rock, with the carvings thrown into sharp relief. It may be necessary for several visits to the rock in differing condition to get a full appreciation of the complex designs. It’s a story-telling rock, a message from a world before written words.

Richard Gregory suggests that,

“Perhaps the ability to respond to absent imaginary situations,” as our early ancestors did with paintings on rock, “represents an essential step towards the development of abstract thought.”

3.1 Stained glass

http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Stained_Glass_Window

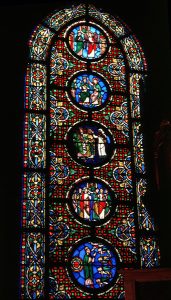

Imagine a world in which everything was bright and shining and new, a world in which one thing reflected off another in such a way as to enhance the attractiveness and beauty of both—and further, that the visual quality of reflection and transparency was an indication of a higher, moral order, an order which was the beginning of the ultimate reality, which, in a word, reflected heaven. This is the concept of ‘claritas’ as it was understood in scholastic philosophy of the thirteenth century and probably earlier. It was the most highly prized of medieval visual qualities.

Fig 3.2 Window, St Denis, Paris

Most of the aesthetic issues that were discussed by Christians in the Middle Ages were inherited from Classical Antiquity. The Classical world had turned its gaze on nature but the Christians turned their gaze on the Classical world. They tended to look upon nature as a reflection of the transcendent world. Along with this they possessed a sensibility capable of fresh and vivid responses to the natural world, including its aesthetic qualities. Beauty for the Medievals did not refer first to something abstract and conceptual. It referred also to everyday feelings, to lived experience..

For the medieval theologian St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), a beautiful thing had three primary characteristics

- Integritas (wholeness)

It must not be deficient in what it needs to be most itself.

- Consonantia (proportionality

Its dimensions should suitably correspond to other physical objects as well as to a metaphysical ideal, an end.

- Claritas (radiance)

It should clearly radiate intelligibility, the logic of its inner being and impress this knowledge of itself on the mind of the perceiver.

These rules of medieval aesthetics were embedded in the archectural proportions and the luminosity of stained glass windows (Fig 3.2). They crystallized because all the philosophers in Middle Ages considered them as allegories, symbols and mysticism which came from the allegorical and mystic interpretations of the Bible. Robert Grosseteste (1175-1253), a bishop philosopher, tried to unify the two aesthetical rules. In Grosseteste’s philosophy the concept of light played a role as important as the geometrical concepts. He was one of the philosophers who developed a so-called “metaphysics of light.” He affirmed the material world had appeared for the first time as light. The form which the world had taken resulted from the radiation of the light. Because light radiates in right lines, it conferred to the world a geometrical form. This way it has the beauty of the form. So, the metaphysics of light ties with it`s geometrical cosmology and both tie with aesthetics of cathedrals and churches..

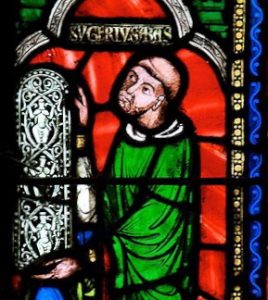

The twelfth century provides a prototype of the medieval man of taste and the art lover, in the person of Suger, Abbot of St. Denis. A statesman and a humanist, Suger was responsible for the principal artistic and architectural enterprises on the Ile de France. He was a complete contrast, both psychologically and morally, to an ascetic like St. Bernard. For the Abbot of St. Denis, the House of God should be a repository of everything beautiful. King Solomon was his model, and his guiding rule. The Treasury at St. Denis was crammed with jewellery and objets d’art which Suger described with loving exactitude. Thus, he writes of;

a big golden chalice of 140 ounces of gold adorned with precious gems, viz., hyacinths and topazes, as a substitute for another one which had been lost as a pawn in the time of our predecessor . . . [and]… a porphyry vase, made admirable by the hand of the sculptor and polisher, after it had lain idly in a chest for many years, converting it from a flagon into the shape of an eagle.

And in the course of enumerating these riches he expresses his pleasure and enthusiasm at ornamenting the church in such a wondrous manner (Fig 3.3).

Fig 3.3 Window, St Denis, Paris

Suger is thus like the other collectors of the Middle Ages, who filled their storehouses not just with artworks, but also with absurd oddities. The duc de Berry’s collection included the horn of a unicorn, St. Joseph’s engagement ring, coconuts, whales’ teeth, and shells from the Seven Seas. It comprised around three thousand items. Seven hundred were paintings, but it also contained an embalmed elephant, a hydra, a basilisk, an egg which an Abbot had found inside another egg, and manna which had fallen during a famine. So we are justified in doubting the purity of medieval taste, their ability to distinguish between art and teratology, the beautiful and the curious.

Suger himself adopted the positions sanctioned at the Synod of Arras in 1025, that whatever the common people could not grasp from the Scriptures should be taught to them through the medium of pictures. Honorius of Autun wrote that the end of painting was threefold: one was ‘that the House of God should be thus beautified’; a second was that it should recall to mind the lives of the Saints; and third. ‘Painting . . . is the literature of the laity’ [pictura est laicorum litteratura]. The accepted opinion as far as literature was that it should ‘instruct and delight’, that it should exhibit both the nobility of intellect and the beauty of eloquence.

In the construction of the Abbey of St. Denis, Abbot Suger was the first to employ flat-bed building techniques, a method invented in the 5th and 6th century buildings of the Near East and Greece. This move away from methods influenced by those used in the Roman Empire, allowed the construction of the characteristic Gothic cathedrals, with their immensely high vaulted ceilings. The walls were constructed completely of dressed stone with little reliance on mortar, thus the result enabled great reduction in the interval between windows. Unlike the preceeding Romanesque architecture, with it’s singular windows cut into thick walls, the Gothic design enabled much larger areas of glazing and greater relationship between each window. This resulted in a unification of the windows and the architecture which was different to that that had gone before. The stained glass was incorporated into this structure with the intention of manipulating light entering the building and creating an atmospheric storytelling effect. Hitherto, with the close construction of Romanesque architecture, the individual widely spaced, deep-set windows piercing the thick walls afforded a series of separate experiences rather than a generally dispersed atmospheric experience. It was as though the viewer went from transparent icon to transparent icon as he progressed up the aisle. Suger, by employing the new flat-bed technique of construction, reduced the interval between the windows and cut down the bulk of the stone-work. Consequently the eye was enabled for the first time to take in a broad sweep of window expanse rather than individual points of interest. This unifying gesture towards not only the windows but also the interaction of the windows with the architecture was the great breakthrough, and on this new formal reality the rest of the achievement of stained glass in the Middle Ages depended.

The purpose of stained glass windows in a church was both to enhance the beauty of their setting and to inform the viewer through narrative or symbolism. The stained glass window of the Middle Ages represents a profound intersection of material reality and spiritual vernacular. Though not an invention of the time, the medium fully matured and was articulated as never before in the walls of twelfth and thirteenth century European cathedrals. Many of these networks of glass and lead no longer survive. Those that do still speak today of their attempt to instil a sense of divine presence, manifest in light and colour.

The commonest method of making stained glass is to carefully cut pieces of glass, fire them and set them in lead calms (sometimes called cames). The calms are small bars of lead so grooved on either side that the glass can be slotted in and held. Where the calms abut or join up they are neatly soldered together. The whole mass of interlocking lead and glass is gradually built up into a panel which, when it has been soldered on both sides, is a manageable unit. After making the panel watertight by means of a loose boiled-oil putty rubbed into the cracks and carefully cleaned off, it is ready to be assembled into a scheme of many panels, building up into a total window.

Metallic oxides (usually from the ashes of beech trees) fired in proportion with silica harvested from sand produced a usable range of colour. This connection to a point of origin, coupled with the theology seems to have shaped the stained glass artist’s relationship with the medium. An understanding cultivated by knowledge of local processes allowed glass painters to work skillfully with glass’ inherent properties. It’s important to recognize that, while artists also painted detail to enhance a window’s narrative, stained glass is essentially an art of light modulation.

The power of the experience of Medieval stained glass lies in its integration with a theology of light and colour. As a transparent as well as a coloured material, glass resonated profoundly with the concepts of clarity and opacity that functioned as primary dichotomies for both moral and ontological systems. Light was transparent as it left the Creator, acquiring colour, and thus its ability to be visible, as it penetrated the material world. Colours can therefore be seen as representing the diversity and imperfection of creatures, although they still betray the radiance of their origins.

Theology speaks to an individual’s present state as well as the one to come and the notion of stained glass windows as the poor man’s Bible is not without cause. The parish community of the middle ages was often illiterate and even picture Bibles were expensive. But a fuller reading of their theological purpose points to the storytelling function of most medieval art where the human figure is concerned. The windows are not so much the Bible of the poor as the proof that there was a vigorous tradition of preaching the Bible to the poor which cried out for illustration as a mnemonic after the sermon. Isolated panels of glass which have survived indicate that the lives of the Old Testament patriarchs were recorded by the medieval glass painters. The choice of some Old Testament subjects and the neglect of others is puzzling until it is realized that the selection was based on the belief that Old Testament events prefigured those of the New Testament. In terms of form, stained glass of the middle ages favoured representation over abstraction. Reyntiens aligns this tradition with the doctrine of the “Communion of Saints” which was as old as Christianity itself.

The doctrine was, briefly, that there is an unbroken web of contact and mutual help between those who have died in the favour of God and those, in the Church, who are yet on this earth. This difficult doctrine was of such importance because the intercession of the saints on behalf of those still living meant that a cultus of the saints was a pressing necessity. This fact, together with the Doctrine of the Incarnation, which stated that the Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, was at one and the same time truly man and truly God, fixed the consciousness of western, Christian, art towards the human figure rather than abstraction or geometric non-figuration. And it is on the basis of figuration that all the glass in the Middle Ages, with very few exceptions, was founded.

The medieval lay masters wanted to control their materials, and to bend and fashion them in such a way that anything was possible. They vaulted huge spaces on slender points of support. They introduced light into their enormous covered spaces in such a way that this light itself constituted a kind of decoration, indeed painting. There were no longer walls but rather translucent tapestries. One has the impression that the source of the light is in the coloured glass itself and one has the feeling of being taken into distant space.

As Peter Hitchens has written, “What Chartres represents is a map and model of the cosmos enabling anyone with eyes to see to find an explanation of the spirit which motivates the universe, which arranges the stars and the comets in their orbits and courses, and which also causes our consciences to burn within us, and our eyes and ears to recognise truth and beauty when we see them. It is not literal, and not for the literal-minded. But then again, nor are poetry or music. And it is almost a cliché to say that Chartres is poetry and music, frozen into stone and glass.

Most of the glazing of the 176 windows was accomplished between around 1200 and 1235 Chartres Cathedral provides a hierarchy of time and space, putting everything into an eternal perspective.Writing about the windows at Chartres, Louis Gillet says, “No prince has owned a book of comparable illuminations.” Windows narrating a progression of events, such as the life of Christ (or of the Blessed Mother, or of a saint), displayed a series of vignettes based on Scriptural sources, apocryphal texts with anecdotal details (mostly about the life of Mary), and a medieval compendium of the saints’ lives. The stories are told by gestures and poses. Everything is abbreviated in a highly expressive form of narrative shorthand (Fig 3.4).

Fig 3.4 The Virgin and Saint John, from a Crucifixion, German, c. 1420, J. Paul Getty Museum.

In the thirteenth century, stained glass had been part of a living cosmology of materials. By the sixteenth century it was not unusual for the glass painter to be given the task of imitating fresco wall paintings n stained glass . Engraved reproductions of such works were being circulated throughout Europe, and these were being accepted by the newly ascending mercantile patron as the final word in taste. Fine Art had been born and was beginning to be ‘applied’ to certain of the traditional arts. In this new hierarchy easel painting had become supreme and all of the other arts were practically shamed into imitating its effects. With his own standards of excellence thus revoked, the stained-glass artist, like the tapestry maker, illuminator, and mosaicist, was reduced to a common labourer.

3.2 Indian painting

Painting has a very long tradition and history in Indian art. The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of pre-historic times, the petroglyphs as found in places like Bhimbetka rock shelters, some of the Stone Age rock paintings found among the Bhimbetka rock shelters are approximately 30,000 years old. India’s Buddhist literature is replete with examples of texts which describe palaces of the army and the aristocratic class embellished with paintings, but the paintings of the Ajanta Caves are the most significant of the few survivals. Smaller scale painting in manuscripts was probably also practised in this period, though the earliest survivals are from the medieval period. Mughal painting represented a fusion of the Persian miniature with older Indian traditions, and from the 17th century its style was diffused across Indian princely courts of all religions, each developing a local style. Company paintings were made for British clients under the British raj, which from the 19th century also introduced art schools along Western lines, leading to modern Indian painting, which is increasingly returning to its Indian roots.

Indian paintings provide an aesthetic continuum that extends from the early civilisation to the present day. From being essentially religious in purpose in the beginning, Indian painting has evolved over the years to become a fusion of various cultures and traditions.

Paintings are more than just pictures in a frame—they are unfolding stories with multiple perspectives. For example, Indian paintings have been described by B.N. Goswamy as layered objects in which one thing, or thought, is gently laid upon another presenting a layered world of meaning. Therefore, he says, to extract a painting’s riches and experience the joy of discovery, the viewer must summon energy, enthusiasm and the excitement of anticipation to become visually immersed in the layers. This process of understanding begins by interrogating a work to reveal the main message of its maker. He suggests that it will then fall into one of the following four categories of meaning. It will present an observation, a passion (expressed as longing and love), a contemplation or a vision. This classification system cuts across historical and cultural divisions.

Because they are based on the layering of meaning Goswamy’s categories are not rigid, Visions can be informed by passion; observation can lead to contemplation, or it can, equally, be the other way—or any other way—around: contemplation can spring from visions, and observation can be expressed in terms of passion. Each person, however, has to approach all these works, and these sections, in his/her own way.

i Observation

Fig 3.5 Untitled (Manoj Dutta, 2018)

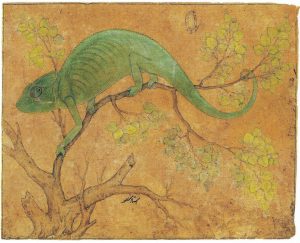

The paintings in this category of meaning are mostly based on real sights, people and scenes, seen or imagined by the painter; and some of them especially commissioned by a patron. Naturally, portraits figure large in this group, as do scenes of palace life and princely pursuits, even though these are sometimes modified, reconstructed and given an unusual twist: e.g. the emperor Jahangir looking at a portrait of his father in one, shooting arrows at ‘Poverty’ in another; a rendering of the emperor Akbar, breaking the conventions of royal portraiture, with his eyes lowered in repose; a towering Raja Sidh Sen of Mandi.. Some of these `observations’ capture an inner reality: a dying Inayat Khan gazing into nothingness; a hunter becoming the hunted as a lion pounces on him; a pool with herons (Fig 3.5 )a chameleon sitting utterly still yet casting a sly eye at everything around him (Fig 3.6).

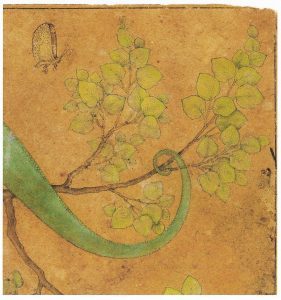

Fig 3.6 A Chameleon

Leaf, now in an unbound album Opaque watercolour on paper Mughal, Jahangir period; by Mansur; c. 1600 11 cm x 13.7 cm Royal Library, Windsor Castle.

As the painter Mansur renders it, this chameleon perched on the branch of a sparsely leaved tree, is evidently eyeing some insect. It has already changed its colour to the green that matches the leaves around him, but it is the coiled-spring-like tension in the body, claws firmly latched on to the branch, the tail curling up and, above all, the look in its sly eye—alert and all-knowing—which compels attention.

The skin of the lizard is brilliantly rendered—’exactingly, tactilely dotted all over with shaded green spots, and its spine . . . saw-toothed from neck to tail with perfect points of colour’, as the art historian Cary Welch has noted. Mansur’s observation is remarkable and Welch, in his colourful description, envisions the painter `on all fours, inching his way through a thicket towards its prey, cunning and silent as a cat’. If a twig had snapped, he adds, ‘the chameleon would have fled, and this miraculous picture would not exist!’

It is difficult to date this painting and judgements range from 1595 to 1615. The likelihood of its having been made in the later Jahangir period is greater.

The painter, Mansur, about whose antecedents one knows virtually nothing, was truly a man of extraordinary talents. The painter’s range of work is extraordinary—from historical scenes recorded in chronicles to illuminations, from individual portraits to renderings of groups. But it is as a painter of flora and fauna that Mansur was without a rival. A wonderful range of flowering plants apart, paintings of falcons and hawks, partridges and cranes and barbets, hornbills and pheasants and peafowls bear his name. Each is a masterly study. If a zebra was brought in from Abyssinia, it was Mansur who was called upon to draw a ‘portrait’ of the uncommon beast; if a turkey cock was brought in by a noble from Goa, and the emperor went into a paroxysm of delight at the sight of this ‘strange and wonderful’ bird, ‘such as I had never seen’, it was Mansur once again who was asked to paint it `so that the amazement that arose from hearing about them might be increased’. Clearly, it was this master painter’s uncanny powers of observation and his mastery of brush and palette (Fig 3) that made him the emperor’s first choice

Fig 3.7 Enlarged portion of Fig 3.6

ii Longing and love

The paintings under this division are largely those inspired by poetic texts. Iin them, lovers cling to each other against a landscape glowing with the exuberance of spring; languid heroines lie lost in thoughts of absent lovers; Radha and Krishna gaze silently into each other’s eyes on the banks of the river Yamuna; Princess Champavati with her exquisite ‘lotus face’ confuses the bumble bees who, instead of heading to the lotus pond, swarm around her.

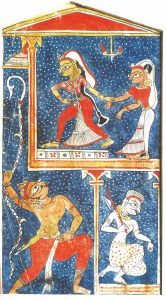

Fig 3.8 An elopement

Folio from a Laur Chanda manuscript Pre-Mughaljainesque; middle of the fifteenth century 18.2 cm x 10.5 cm Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi.

As night descends, a drama begins to unfold 3.8. The lover, Lorik—hero of Mulla Daud’s celebrated Avadhi romance in verse, Chandayana, more popularly known as Laur Chanda—arrives at the palace of his beloved, Chanda, in the middle of the night. His entry is unnoticed, for the sleepy guard at the gate of the palace has almost dozed off. Lorik throws a rope for his lover waiting in the upper storey so she can slide down. Chanda advances eagerly to catch the end of the rope while a palace lady attempts in vain to stop her. Lorik stands below, looking above, his body tense.

There is lyricism in Mulla Daud’s words, but even more so perhaps in the manner in which the unnamed painter renders them here. With a sense of remarkable freedom, he creates a world of his own in which there are no correspondences to reality. The royal palace is stripped down to a bare skeleton, with no walls, doors or windows. Only a flattened angular dome and slender pillars provide a hint of opulence.

The inky-blue night sky seems to have descended to the earth, consuming the background with countless stars. All the figures remain clearly etched in perfect light, although the lone hanging lamp tells the viewer that the day is long gone and night has fallen. With great forethought, some areas are left uncoloured, exposing the white sheet on which it is painted. There is a space enclosed within the billowing veils of the two young women, or the outline of Chanda’s long, trailing braid. The snaky rope that Lorik has thrown up remains suspended in the air on its own, defiantly, and decoratively, without having reached Chanda’s hands.

The forms of the figures are all remarkably stylized. While the athletic-looking Lorik has the torso of a lion—broad chest, narrow waist—and holds his hands in studied gestures, Chanda and her companion are slim of build. Chanda’s waist is so slender that it is almost at the point of disappearance. The eye travels to Chanda’s uncommonly small breasts too, for the painter wishes us to notice that she is barely a woman.

The faces, seen in true profile, are sharply chiselled. But it is the eyes of all the four figures that compel attention. They are heavily elongated under those fine wavy lines that mark the eyebrows. While one eye seen in profile extends virtually to the ear, the other eye is suspended in the air, just outside the contours of the face. This points clearly to the work’s ‘Jain’ ancestry where one sees a similar treatment. Though there is not much attention to the articulation of the hands and feet which remain awkwardly inelegant, one can see the remarkable sophistication of other aspects of this folio. Stylistically, it bears the clear impress of the Jain or western Indian group of works, but one knows that those works did not all come from Gujarat or Rajasthan and were not all Jain in content.

iii Contemplation

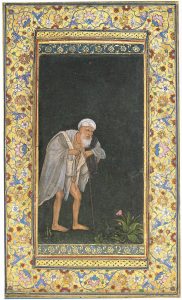

An old pilgrim in tattered clothes moves haltingly forward, his expression suggesting he is reflecting over his life and the one hereafter (Fig 3.9).

Fig 3.9 Intimations of mortality

Leaf, possibly from an album Opaque watercolour on paper Mughaljahangir period, by Abu’! Hasan; c. 1618-20 11.1 cm x 6.5 cm. The Aga Klan Collection, Toronto

Abu’l Hasan, a great painter at the Mughal court—Nadir-al Zaman is the title that the emperor Jahangir conferred upon him, meaning ‘Wonder of the Age’—moved away in one of his works from the glitter of power and opulence to paint an old, fragile man. The tone of the painting is hushed and one falls silent looking at the lone, hesitantly moving figure. The man—an old pilgrim perhaps or, possibly, a mendicant who has seen better days—stands barefoot, leaning on a thin, long staff as he struggles to move forward. The body bears witness to the ravages of time: the bent back, the stooped shoulder, the snow-white beard, the lean, desiccated frame. But one can see, from the look in the eyes, that the mind is still keen and the bent of mind religious—he holds prominently a rosary of beads in his bony right hand and wears one round his neck. There are signs of indigence everywhere: the lower part of the body is bare, the feet are unshod, and the coarse apparel he wears consists mostly of a rough cloak used as a wrap, a folded shawl-like sheet thrown over the left shoulder, and an unadorned tightly bound turban.

Technically, the work is brilliant, one notices the roughness of the skin at the knees, the thinness of the fingers of the hands, the rendering of the beads in the rosary, each shrivelled and varying in size; above all, the virtuoso treatment of the face with its sage lines of age and experience.

Fig 3.10 Enlarged portion of Fig 3.9.

Technically, the work is brilliant in all its detail (Fig 3.10). One notices the roughness of the skin at the knees; the thinness of the fingers; the rendering of the beads in the rosary, each shrivelled and varying in size; above all, the face with its lines of age and experience.

At the same time, as far as we are concerned, does the work resonate within us? Does it give rise to thoughts in our own minds, perhaps even remind us of parallels, of something we had once read and were moved by?

iv Visions

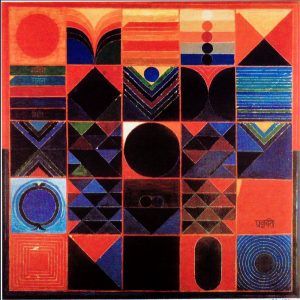

Fig 3.11 Prakriti (Raza;1990)

This is how a contemporary Indian painter explains his picture (Fig 3.11) representing the development of Bindu. Bindu is a Sanskrit term meaning “point” or “dot.” … Sometimes this bindi dot is considered to represent the point of Consciousness from which the universe originates.

“Forms emerge from darkness. Their presence is perceptible in obscurity. They become relevant if their energy is oriented through vision into an alive form-orchestration for which certain prerequisites are indispensable.The process is akin to germination. The obscure black space is charged with latent forces asking for fulfillment. Like the universal natural order of the ‘earth-seed’ relationship, the original unit, ‘Bindu’, emerges and unfolds itself in the black space. All inherent forces unite. A vertical line intersects a horizontal line, engendering energy and light. Space is charged. Contours appear: white, yellow, red and blue, and along with the original black, they compose the colour spectrum of the visible world”.

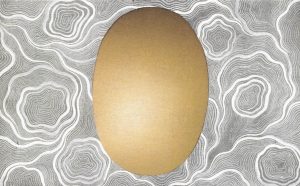

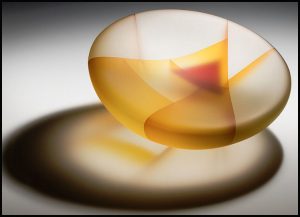

The paintings that come under Goswamy’s category of ‘Visions’ are chiefly those that depict sights and events unseen, but that have for long been part of our ‘awareness’ and imagination. Visions includes images of abstraction like Hiranyagarbha, the Cosmic Egg, (Fig 3.12) floating on the waters of eternity, or the golden mount, Meru. Here, too, are iconic images of goddesses bestowing grace or striking fear; and of divine couples looking down from snowy peaks. Then there are works relating to mythologies or heroic tales: the Ramayana, the Bhagavata Purana, the Speaking Tree. Krishna holds a mountain aloft on the palm of his hand; seven-storeyed vehicles rise in the air; trees speak; cows levitate in the air; the great hero Hamza battles dragons breathing fire; and Neptune roars through the oceans.

Fig 3.12 Hiranyagarbha; the Cosmic Egg Folio from a Bhagavata Puma series Opaque watercolour and gold on paper Pahari, by Manaku of Guler; c. 1740 21.8 cm x 32.2 cm (outer) 17.6 cm x 28 cm (inner) Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi

Among the many speculations about the Origins of Creation, the Beginnings of it All—something that Indian thought is rich in—there are references to the wondrous, mysterious ‘golden womb’ or `golden egg’. One of the oldest Puranas, the Matsya Purana, has this account of the beginnings of creation: after Mahapralaya, the great dissolution of the Universe, there was darkness everywhere and everything was in a state of sleep. Then Svayambhu, the Self-Manifested Being, arose—a form beyond senses. It created the primordial waters first and placed the seed of creation into it. The seed turned into a golden womb, the Hiranyagarbha. Then Svayambhu entered the egg.

In the course of painting his great Bhagavata Purana series, the painter Manaku spread the ‘primordial waters’ that the texts speak of over the entire surface of the page. There are no waves here, no great commotion, only concentric whirlpools and eddies, like giant rings of time on timeless waters. And in their midst, unmoving, completely still, floats the great golden egg, a perfect oval, seed of all that there is going to be.

A fascinating detail about this painting: when one sees the painting laid fiat, the egg appears a bit dark, almost dominated by browns. It is when you hold the painting in your hand, as it was meant to be, and move it ever so lightly that it reveals itself: the great egg begins to glisten, an ovoid form of the purest gold. true hiranya, to use the Sanskrit term for the precious metal.

(B.N. Goswamy ((2916) ‘The Spirit of Indian Painting’)

http://unurthed.com/2008/07/06/razas-prakriti/

4 Anatomical representationalism

Fig 4.1 Concept map off anatomical representationalism

Art and science first came together in the late 15th century and Albrecht Durer was one of the main drivers. Dürer was a German painter, engraver and mathematician. He was born on May 21, 1471 and died on April 6, 1528 in Nuremberg. Dürer established his reputation and influence across Europe when he was still in his twenties due to his high-quality woodcut prints. He was in communication with the major Italian artists of his time, including Raphael, Giovanni Bellini and Leonardo da Vinci, His vast body of work includes engravings, his preferred technique in his later prints, altarpieces, portraits and self-portraits, watercolours and books. His watercolours mark him as one of the first European landscape artists, while his ambitious woodcuts revolutionized the potential of that medium. His introduction of classical motifs into Northern art, through his knowledge of Italian art, has secured his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical treatises, which involve principles of mathematics, perspective, and ideal proportions. In this connection, he realised the importance of using grids when investigating form. He found they were essential when trying to draw human figure objectively and when developing perspectives he realised that similar mathematical principles were required to unify all the elements in his works.

The creation of images of spatially separated objects led to the invention of perspective machines, which bring optics and the geometry of perspective close together. The devices have the aim of helping artists to draw what they see, In his “Underweysung” Dürer described four devices to draw perspectives, which have some similarities but also differences. In the most well-known of these devices a grid is placed in front of the object and the squared drawing surface corresponds with this grid. By looking through the grid, objects become divided up into squares. The eye position is fixed with the help of a stick or hole. It is a drawing tool with the advantage that an image can be drawn of the seen object in a bigger or smaller scale. This process makes it easier to work out where each object is in relation to everything else around it.

The artist using the drawing machine would have a piece of paper in front of them with the same number of squares as in the wooden frame. Everything the artist wanted to draw would be transferred from the square where they saw it in the grid, onto its twin square on the piece of paper. In creating a human portrait, if the artist saw a person’s nose halfway down the fifth square up and the second square across, then that is where they would draw it on the matching paper square. By using the drawing machine, artists found out just how distorted the world appears when you look at it from odd angles (Fig 4.2 )

Fig 4.2 A 16th century drawing machine

Panofsky gives three reasons why the technique of perspective was received with such a universal enthusiasm in the 16th century. First, the placing of an object anywhere in a picture and the production of a certain distance and point of location symbolised a time in which man was positioned in the centre of the universe. Second, perspective satisfied the new craving for exactness and predictability. And third, the application of mathematical formulae to make art agreed with Renaissance aesthetics.

Latour goes further and states that perspective is a form of fiction;

“… even the wildest or the most sacred […] things of nature – even the lowliest – have a meeting ground, a common place, because they all benefit from the same ‘optical consistency’. Not only can you displace cities, landscapes, or natives and go back and forth to and from them along avenues through space, but you can also reach saints, gods, heavens, palaces, or dreams”

Geometrical longitude and latitude in a picture create the perception in the viewer of standing right in the middle of a picture The observer was no longer detached from the painting, but a full part of it – the artist became a manipulator of visual images, able to “play perceptual games” with the viewer. Dürer’s work on geometry, ‘Instruction on Measurement’, is the first document to treat a representational problem with a scientific answer. He points out that perspective is not a technical discipline limited to architecture and painting, but rather an essential part of mathematics.

Like perspective, proportion also has an underlying mathematical expression.. What perspective is for the ‘room’ in a painting, so proportion is for the human or animal body as a whole. Dürer sought to set up geometrical explanations for proportions, merging each body part with a geometrical form:

“The total length and general axis of the body is determined by a basic vertical […] The Pelvis is described as trapezoid, and the thorax in a square […] The head, if turned in profile, is inscribed in a square, and the contours of the shoulders, hips and loins are determined by circular arcs”.

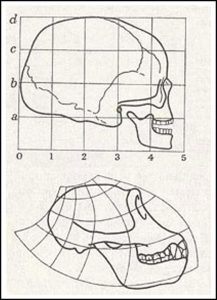

Durer soon realised that he could not apply this model to every human being and abandoned the geometrical curves in his drawings, stating that “the boundary lines of a human figure cannot be drawn with a compass or ruler”. Instead he decided to consider a series of female and male body-types, which he assembled in his Four Books on Human Proportion (published posthumously in 1528). One of his aims was to use transformations of human heads drawn against a coordinate grid to understand facial variation . This was a very powerful way to demonstrate how otherwise disparate shapes can be meaningfully compared.

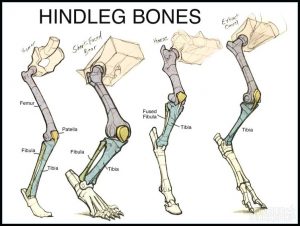

Species ecology

The most useful ecological category to link art with science is species ecology. Within this ecology art is expressed practically as the scientific subject of comparative anatomy, which explores and establishes the correspondences between body parts of organisms within and between species. It systemises and communicates similarities and differences pictorially. These illustrations in terms of the design creativity of the illustrator are art works (Fig 4.3 ).

Fig 4.3 Comparison of hind leg bones of human, short-faced bear, horse and extinct camel

Four centuries after Durer, the zoologist D’arcy Thompson took up the grid method as a way of defining the process by which evolution has produced different shapes and forms . Durer had used it to study perspective and human proportions. Thompson used it to relate biological shapes to each other via geometric transformations of the grid. Thompson’s most famous set of observations in his book ‘On Growth and Form’ were the outcome of his search for a mathematical logic to compare bodily forms. What makes Durer’s grid method particularly useful is that it allows for continuity, for gradual growth and development or transformation, whereby certain regions or features, such as the head of a primate, are stimulated to grow faster than other parts (Fig 4.4).

Thompson’s book is almost an encyclopedia of all the relations that have ever been discussed between mathematics and organic form. Among the subjects treated are: the form of the cell, tissues, concretions produced by living things, shells, horns, and teeth; from the dynamic point of view, growth and the relation between form and mechanical efficiency; and such perennial favourites of the geometrician as the form of the bee’s cell and the arrangement of leaves.

‘On Growth and Form’ has inspired thinkers including the biologists Julian Huxley, Conrad Hal Waddington and Stephen Jay Gould, the mathematician Alan Turing, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss and artists including Richard Hamilton, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Ben Nicholson. Jackson Pollock owned a copy. Waddington and other developmental biologists were struck particularly by the chapter on Thompson’s “Theory of Transformations”, where he showed that the various shapes of related species (such as fish) could be presented as geometric transformations, anticipating developmental biology of a century later. The book led Turing to write a famous paper “The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis” on how patterns such as those seen on the skins of animals can emerge from a simple chemical system. Lévi-Strauss cites Thomson in his 1963 book Structural Anthropology. ‘On. Growth and Form’ is seen as a classic text in architecture and is admired by architects “for its exploration of natural geometries in the dynamics of growth and physical processes.” The architects and designers Le Corbusier, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy and Mies van der Rohe were inspired by the book. Peter Medawar, the 1960 Nobel Laureate in Medicine, called it “the finest work of literature in all the annals of science that have been recorded in the English tongue”.

Fig 4.4 Convertion of a the skull of a lower primate into a human skull by differential growth of its parts.

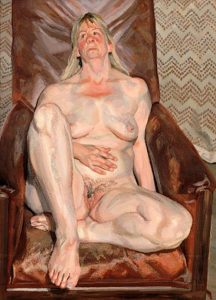

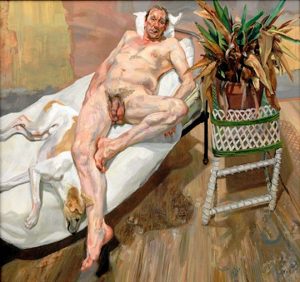

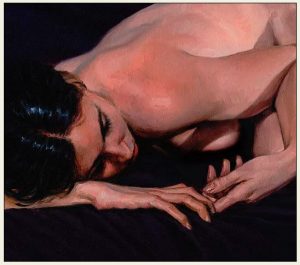

Comparative anatomy is the channel by which artists depict the human figure seen as a pure animal form. This is the basis of Lucian Freud’s ‘naked portraits, which created an entirely new genre in the depiction of the human figure. His pictures present subjects as forms not dissimilar from inanimate still life objects, while at the same time rendering painted flesh with an extraordinary, penetrating humanity. These qualities are evident in Figs 4.5-6. By turns clinical and intimate, stark and tender, the art works resulted from weeks of intense sitting by and scrutiny of the artist’s subjects. While the woman in the first portrait goes unnamed, the second picture identifies Freud’s two most constant companions: his long-time studio assistant and friend David Dawson, and his whippet Eli. Both paintings evidence Freud’s almost ruthless process of observation and forensic reckoning of the human body.

Fig 4.5 Naked portrait in a red chair (Lucien Freud,1999)

Fig 4.6 David and Eli (Lucien Freud 2003–4)

“Living people interest me far more than anything else,” Freud stated. “I’m really interested in them as animals. The one thing about human animals is their individuality: liking to work from them naked is part of that reason, because I can see more.”

Freud’s work, and the exaggerated anatomical features arising from foreshortening of the human body has been taken as a model for teaching how to paint the body’s intriguing features ( Fig 4.7 ), particularly those expressed in the seated nude with crossed legs, a classic pose which has long been used as the starting point for abstraction (Figs 4.8).

Fig 3.7 Example of how to paint the female nude

http://www.artgraphica.net/free-art-lessons/oil-painting/female-nude-painting-demo.html

Fig 3.8 Crossed legs

For Freud, seeing more meant defining a human being’s amimalness in the subtle shadows of the skin to reveal every hump and bump of his sitter’s musculature ad adipose tissue. In this respect Freud was known for his uncompromising and forensic style that exposed every inch of imperfection in his sitters. Slabs of fat, birthmarks, disfigurement and dangling genitalia were all brought to life and magnified with an unerring eye.

As an earlier worker obsessed with female anatomy, Willem De Kooning, in his works on paper from 1938 to 1955, represents the female form in varying states of abstraction (Fig 3.9). This group of works provides an invaluable glimpse at the deeply personal process of thinking, creating, and discovery that lies at the core of abstraction. With each drawing and oil sketch, a new artistic progression in the continuous struggle to realize and convey the essence of human anatomy is revealed to the viewer. The pictures express his refined artistic successes and examples of a working out of visual problems on paper and canvas. The works are best characterized by an inherent tension. They vibrate with energy and visual force as they reveal the artist’s struggles to eliminate boundaries between drawing and painting, while probing figurative elements for their fundamental abstract anatomical forms. They read as transparent entries in the diary of a mind.

Fig 3.9 Figarative abstraction, Willem de Kooning

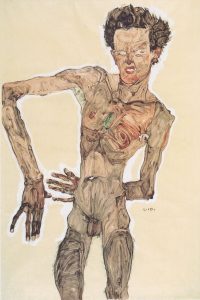

Austrian painter Egon Schiele was a major artistic figure of the early 20th century. Famous for his nude drawings and self portraits, the artist is perhaps known best for his depiction bodies as if flayed to expose the underlying muscles and connective tissue (Fig 3.10).

Fig 3.10 Nude self portrait grimacing Egon Schiele 1910.

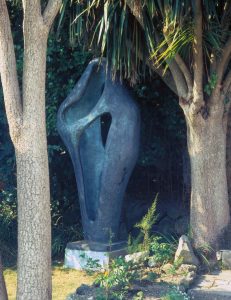

In an interview for Studio magazine in 1946 the sculptor Barbara Hepworth was asked to describe her main sources of inspiration. Anticipating her response, the interviewer volunteered that these included ‘negro sculpture, the human figure, aerodynamics, or dreams’. She replied simply: ‘The main sources of my inspiration are the human figure and landscape; also the one in relation to the other’. In her work she was developing the idea that the artist exists within the visible scene and not apart from it. The sculptures were not an expression of the observed landscape but of the act of observing it Fig 3.11).

Fig 3.11 Figure for Landscape 1959–60, Barbara Hepworth

Figure for Landscape 1959-60 Dame Barbara Hepworth 1903-1975 Presented by the executors of the artist’s estate 1980 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T03140

The metaphorical use of body imagery in relation to landscape is fundamental in the Western world. The Renaissance metaphor that understood the earth to be modelled on the anatomy of the human body has generally been regarded as a one‐way relation, ‘landscape as body. It finds its expression in generic landscape naming. In imaginative literature at least, the reverse relation, ‘body as landscape,’ is of frequent occurrence and continues well into the machine age. The body in question is generally female, and the culmination of the ‘body as landscape’ metaphor is pornotopia.

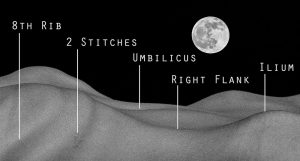

Jane Samuels’ ‘Terrain: Anatomical Landscapes’, is a series of drawings derived from walks around the UK. Walks are documented in photography, drawing and writing. This research informs detailed pencil drawings that each represents a single location. This process creates narrative images that explore the relationship between humans and our rural environment. In combining human anatomy and land, Samuels aims to underline the complicated connection between the science of conservation and politics the: the extent to which we change the land, the conflicts that arise in land management and the political battles that take place in our woods and fields

Carl Warner turns the ridges, hills and valleys of one or more human bodies into strange and surreal landscape photos (3.12).

Fig 3.12 Landscape formed from human bodies. Carl Warner

“[The project] plays on the sense of space in which we dwell,” writes Warner. “The external view of ourselves therefore becomes a more abstract and perhaps more intimate reflection of our inner being when viewed as a landscape or given a sense of place.” This idea is represented in Figs 3.13- 3.16.

Fig 3.13 Landscape #60, Eunice Golden 1972

Fig 3.14 Anatomical landscape II; Desert Moon (Ivana Viani)

Fig 3.15 Elbowscape James Martin

Fig 3.16 Legscape

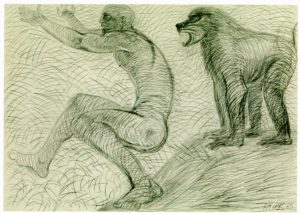

Human animalness dominates the art of Elizabeth Frink. Her take on comparative anatomy is to make anatomical comparisons between humans and other animals. In this she is preoccupied with behavioral contrasts and similarities such as violence, aggression, brutalism, sensitivity, empathy, and nurture. She positions the horrors that men are culpable of committing alongside the day to day internecine violence of lower primates (Fig 3.17 ). Frink’s works question how it is that urban bipeds, responsible for inventing sophisticated creative societies, can behave so violently towards each other. She leaves us to contemplate this inbuilt destructive legacy of 5 million years of evolution of the human form.

.Fig 3.17 Man and baboon Elizabeth Frink

Cellular ecology

Cellular ecology is a scientific concept that encompasses the interactions between the various fluid compartments of the body to regulate the body’s internal activities and its interactions with the external environment. The outcome is to preserve the internal environment for survival of the whole. The control system involves regulated biochemical flows between blood compartments, organs, and their cells. The ultimate fluid compartment is that of cellular organelles, which are parts of cells, as organs are to the body. Together, cells and their organelles form an ecology that permits the prime functions of living organisms—growth, development, and reproduction—to proceed in an orderly, stable fashion. As a system, the body’s cells are exquisitely self-regulating, so that any disruption of the normal internal environment by internal or external events is resisted by powerful counter measures. When this resistance is overcome by environmental factors, illness ensues.

Cellular ecology can be visualised as a curriculum to bring the anatomical organisation of cells into a more dynamic biochemical framework for studying how the components of a cell interact within the cell and how cells interact with their surroundings. In other words cellular ecology is based on an understanding that the whole body is a dynamic entity greater than the sum of the parts. A unifying theme is homeostasis, that living things are constructed, physiologically, biochemically and behaviourally, to maintain a constant internal environment. The concept was first proposed in the 19th century by French physiologist Claude Bernard, who stated that “all the vital mechanisms, varied as they are, have only one object: that of preserving constant the conditions of life’.

Picture making is an important research/recording activity within cellular ecology. Microscopes are used to study the different cellular forms pictorially to reveal their development in growth, ageing and evolution.

The science of comparative anatomy defines how body parts such as organs, bones, nerves and muscles are maintained as living cellular structures in a dynamic biochemical equilibrium with resources and conditions in the external environment (Fig 3.18 ). The human body maintains various physiological conditions within itself, such as temperature, at a constant level. This is not to say that these levels are not subject to change. In room where the temperature is below body temperature, we would be constantly losing heat to the environment. Our bodily functions work against the environment to keep our temperature up. This constant giving and taking away keeps us at a fixed range. This is referred to as a dynamic equilibrium. The body is like a candle flame. Wax is burnt to be continuously replaced by wax drawn up by the wick, whilst the flame maintains its form.

Although we maintain biochemical constancy for certain favourable environmental conditions, there are many factors that keep changing those conditions, and the body works to maintain them at favourable levels.

Fig 3.18 ‘ Moving to stay put’: (pictorial model of homeostasis).

Because scientists are taught not to bring emotions into their research, it is important to see that an increasing number of contemporary artists (and scientists!) are taking on the challenge of using their art to present complex scientific issues in humanistic ways that question our ingrained separative thinking. Only in this manner will we search for humanistic, cradle- to-grave practicai solutions to today’s most critical environmental problems. In this connection, the artists and scientists in 2015-16 Art & Science Collaborations’ SCIENCE INSPIRES ART: Biodiversity/Extinction exhibition at the New York Hall of Science, were selected by because they allowed their feelings of deep concern to guide their ultimate mission – for their art to stimulate public reflection, critical thinking, dialogue, and hopefully individual actions on the issues we face surrounding loss of biodiversity and species extinction. Nature art is a bridge from the viewpoint that the depiction of plants and animals have played an important role in the belief systems of many different societies