Based on the experience of Denis Bellamy who led teachers and students in Wales to rethink pedagogy for the twenty-first century.

Culture: the iceberg model

Fig 1 Culture: the iceberg model

The analogy of “culture as an iceberg” illustrates the complexity of culture (Fig 1). Only the tip is visible (language, food, appearance, etc.) whereas a very large part of the iceberg is difficult to see or grasp (communication style, beliefs, values, attitudes, perceptions, etc.). The items in the invisible body of the iceberg could include an endless list of notions from definitions of beauty or respect to patterns of group decision-making, ideals governing child-raising, as well as values relating to leadership, prestige, health, love, death and so on.

Culture in education

A curriculum that builds on students’ cultural understanding, or allows them to use their personal funds of knowledge about their home culture, has proven to be more effective in changing behaviour because students can relate it to their own lives.

However, it can be difficult to determine how best to accommodate cultural diversity in an education system, but culturally conscious education is becoming more common. However, most people are not educated to look beyond their immediate situation. People tend to experience nature, history, and society through the lens of biography and their own culture. Educating for the 21st century needs a more universal outlook that links personal problems to public issues on a global scale. Individuals can take control over their own lives by becoming aware of the dynamics of their own positions within a global social and natural order. Also, by developing an awareness of all of those individuals in different circumstances, progress can be made toward global understanding and tolerance as people learn to act in their common interests.

The overriding common interest of our time is climate change and its management to avoid a global catastrophe. Providing a solution will necessitate cross-cultural communication. People from various countries, with different backgrounds, have to exchange their ideas and opinions about how to solve this world wide problem in equity. The cultural differences between people influence both the content of their message as well as the way it’s expressed. On this premise alone, bringing culture to the centre of education at all levels is justified. Furthermore, making comparative connections between culture, nature, economics and ecology is key to starting to enact effective policy on climate change that we are just beginning to understand as a system. The effects of climate change will be economic, social, and environmental and because of the complexity of culture will alter people’s lives in a myriad of ways.

Another educational metaphor assumes that culture is structured hierarchically in “layers of building blocks” like a pyramid. This pyramid model (Fig 2). differentiates three levels of ‘software of the mind’: universal, cultural and personal. Geert Hofstede admits that trying to establish where exactly the borders lie between nature and culture, and between culture and the environment created by a personality is a challenge, not least because personalities are probably imbibing a shared cultural commons.

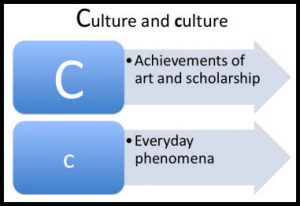

Fig 2 Culture: big C and little c

Our understanding of the term culture depends on which section of the “iceberg” or layer of the “pyramid” we are referring to. As a consequence, there is a wide range of definitions. At one end of the scale we find the traditional, elitist view of culture which concentrates on all products of art and scholarship, including literature, painting, music, philosophy and so on. R J Halverson calls this culture with a capital “C”. At the other end of the scale we find everyday culture, represented by the things we use in our daily life (such as food and drink or dress or technical devices), by our daily actions (comprising work and leisure), by the way we think and feel about and value our possessions and actions and the ways in which others are distinguished from us. This is the area of culture with a lower-case “c”.

In all definitions, culture refers to a “set of signs by which the members of a given society recognize one another, while distinguishing them from people not belonging to that social group.

Hofstede also sees culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another

C Kramsch defines culture as “a common system of standards for perceiving, believing, evaluating, and acting”.

UNESCO offers one of the most comprehensive definitions of culture: the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of a society or social group… [encompassing] in addition to art and literature, lifestyles, ways of living together, value systems, traditions and beliefs.

The traditional view of culture (big C) would be too narrow and static since it does not take into account individuals interacting in multicultural and intercultural settings. Therefore it is essential to emphasise two further aspects of culture when thinking about intercultural education: the comprehensive aspect, which classifies boundaries and group identities and the dynamic aspect which emphasises blending.

Any one of these many definitions and concepts may be taken as the starting point to understand culture. Because of the diversity of the windows and doors into culture it is convenient to think about defining appropriate subdivisions. Culture is often discussed as an economy, but it is better to see it as an ecology, because this viewpoint offers a richer and more complete understanding.

Classification of cultural ecosystems

The term oekologie was coined in 1866 by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel. The word is derived from the Greek οικος (oikos, “household”) and λόγος (logos, “study”); therefore the original definition of “ecology” means the “study of the household [of nature]”

Ecology originally referred to the interrelationships between living creatures and their habitats, but over the years the term has been generalised to mean the set of relationships existing between any complex system and its surroundings. In this broader context of culture as an ecology, we can regard the household of nature as encompassing our place in the cosmos. This point is made everytime a primary school student is taught that they are made from stardust. Cosmos often simply means “universe”, but the word is generally used to suggest an orderly or harmonious universe. Here, we are situated in a dynamic chemical continuum from cells to galaxies embedded in dark matter. Much of the history of cosmology and its theories are a reflection of people and the cultures they lived in. The dominant view at any time is a cultural one and accepted because of the forceful personalities behind the ideas, whether they are scientists or believers in the hand of gods.

Nevetheless, an ecological view of the cosmos recognises organized structures on all different scales, from small systems like Earth and our solar system, to galaxies that contain trillions of stars, and finally extremely large structures that contain billions of galaxies. How and why these organized structures formed and how they influence one another is a major focus of modern astrophysics, which aims to measure properties of individual galaxies and the largest structures in the universe at the same time. This ecological view of the universe allows astronomers to understand how the largest systems influence the smallest ones and how this interplay changes with time. Their ideas can become part of a materialistic culture, which in turn creates stories about how we live on planet Earth, with particular reference to the sky and cosmos as part of the wider environment .

Cultural ecology was defined by Julian Steward in 1937 to describe the study of the processes by which a society adapts to its environment. Over the years cultural ecology has come to define an interdisciplinary subject concerned with the factors that shape culture and how culture shapes its environment, particularly through the discovery, depiction and management of natural resources. An important aspect of ecosystem dynamics is the life cycle of its expressions. It is in this sense that culture is an ecology with within many subcultures.

Seeing culture as an ecology is congruent with approaches to the understanding of human society based on cultural values that take into account a wide range of non-monetary values. This ecological approach concentrates on relationships and patterns within the overall system It shows how careers develop, ideas transfer, money flows, and product and content move, to and fro, around and between the funded, homemade and commercial subsectors of society. Culture is an organism not a mechanism; it is much messier and more dynamic than linear models allow. The use of ecological metaphors, such as regeneration, symbiosis, fragility, positive and negative feedback loops, and mutual dependence creates a rich way of discussing culture. Different perspectives then emerge, helping to develop new taxonomies, new visualisations, and fresh ways of thinking about how culture operates in relation to environment. This kind of thinking results in the definition of many sub divisions of cultural ecology.

Subdivisions of cultural ecology

For convenience of education this dynamic continuum of the universe, when focused on planet Earth, can be divided into five large sub-ecologies of habitats, culture, politics, economics and cells. These are broad, well defined bodies of knowledge dealing with interdisciplinary issues. They are best studied by applying systems thinking to life on Earth, where the old subdivisions of knowledge give too narrow a perspective

There are many smaller subdivisions of cultural ecology such as a ecofeminism, deep ecology. and the ecology of art and ideas. In the former, the crucial issue is the historical relationship between the domination of women and the domination of nature. In deep ecology the tension between biocentrism and human self-realisation comes to the fore.

The essence of deep ecology is to address “deeper” questions. These are questions about human life, society, and nature. In this respect, deep ecology is a conceptual approach or general orientation in our thinking about the industrial model of world development, where people go where the work is. Its standpoint is that major ecological problems cannot be resolved within the continuation of industrial society driven by the existing capitalist or socialist-industrialist economic system. An alternative is regionalism, which claims that strengthening the governing bodies and political powers within a region, at the expense of a central, national government, will benefit local populations in terms of better fiscal responsibility to implement local policies and plans.

Bioregionalism gives place a cultural ecology perspective because it is a political, cultural, and ecological system or set of views based on naturally defined areas called bioregions. Bioregions are defined through physical and environmental features, including watershed boundaries and soil and terrain characteristics. Bioregionalism stresses that the determination of a bioregion is also a cultural phenomenon, and emphasizes local populations, knowledge, and solutions for living sustainably.

Bioregionalism is often presented as the politics of deep ecology, or deep ecology’s social philosophy. This is the view that natural features should provide the defining conditions for places of community, and that secure and satisfying local lives are led by those who know a place, have learned its lore and who adapt their lifestyle to its affordances by developing its potential within ecological limits. Such a life, the bioregionalists argue, will enable people to enjoy the fruits of self-liberation and self-development.

Bioregional awareness teaches us in specific ways. Gary Snyder says It is not enough to just ‘love nature’ or to want to ‘be in harmony with Gaia.’ Our relation to the natural world takes place in a place, and it must be grounded in local information and experience. A bioregion provides livelihoods, not just amenity. It builds on existing relocalisation and a circular economy that measure where resources come from; identify ‘leakages’ in the local economy; and explore how these leaks could be plugged by locally available resources. It can be as large as a watershed or as small as a village.

These ecologies all promote the use of concept maps and mind maps as aids to comprehension of the whole. This type of mapping system begins with a main idea or subject that then branches out to show how it can be broken down into specific topics with connections between them.

The term “political ecology” was first coined by Frank Thone in an article published in 1935 (Nature Rambling: We Fight for Grass, The Science Newsletter 27, 717, Jan. 5: 14). Political ecology is the study of the relationships between political, economic and social factors. In particular, it deals with the politicizing of environmental issues. It includes the issues of resource access and utilization with an overarching world-system framework. From this viewpoint colonialism is an ecology with many case histories. For some time, Jason W Moore has vigorously promoted himself as the inventor and chief theorist of something he calls “world-ecology”, described in this book as “a way to think through human history in the web of life”.1 In his view, which he presents as an extension of Marxism, Europe’s pillage of human and natural resources in the Americas in the 16th century established a capitalist world-ecology that continues to this day. All subsequent developments, including the industrial revolution, imperialism, monopoly capital and neoliberalism, are just adjustments within the 16th century framework, caused by long-term shifts in the cost of the “cheaps”—mainly raw materials and workers—that capitalism requires.

Other cultural ecologies

The concept of economic ecology is not to design an ecological economics where ecology is merely one element of economic theory, but rather an economic ecology where human economy is fully integrated into the habitat ecology of the planet

The concept of cellular ecology encompasses the interactions between the various fluid compartments of the body to regulate the body’s internal activities and its interactions with the external environment to preserve the internal environment. The control system involves the regulated biochemical flows between blood compartments, organs, and cells. The ultimate fluid compartment is that of cellular organelles, which are parts of cells, as organs are to the body. Together they form an ecology that permits the prime functions of living organisms—growth, development, and reproduction—to proceed in an orderly, stable fashion. As a system, the body’s cells are exquisitely self-regulating, so that any disruption of the normal internal environment by internal or external events is resisted by powerful counter measures. When this resistance is overcome, illness ensues.

Cellular ecology developed to bring the anatomical organisation of cells into a more dynamic biochemical framework for studying how the components of a cell interact within the cell and how cells interact with their surroundings. In other words cellular ecology is based on the understanding that the whole body is dynamic and greater than the sum of the parts. A unifying theme is homeostasis. The concept of homeostasis—that living things maintain a constant internal environment—was first suggested in the 19th century by French physiologist Claude Bernard, who stated that “all the vital mechanisms, varied as they are, have only one object: that of preserving constant the conditions of life.”

On such subculture for example is the ‘creative’ industries defined by the dynamic components of advertising, fashion, theatre, film and video games. The ecology of art and ideas deals with ‘the complex interdependencies that shape the demand for and production of arts and cultural offerings’ . It is set out in the following mission statement of the University of New Mexico with particular reference to its art and ecological resources,

“The University of New Mexico provides an environment where creativity, experimentation, and intellectual discourse can flourish, the Department of Art demonstrates a strong commitment to its community of Studio Artists, Art Educators and Art Historians. The Department recognizes the advantages that are gained through the integration of these disciplines and through broader association with other disciplines and research units across the university. Creative and intellectual energy generated by crossing boundaries benefits our graduate and undergraduate students and prepares them for an ever-changing global culture. Art & Ecology courses encourage students to investigate, question, and expand upon inter-relationships between cultural and natural systems. Our courses place emphasis on methods and tools from many disciplines—including the fine and performing arts, design, the sciences, and activism—to foster collaborative and field-based research and art-making. We view art as an agent of analysis, critique and radical change. We are less bound to traditional media and more to stimulating ideas and new forms of public engagement and aesthetic experience”.

A curriculum for the 21st century

“Stories exist,” says Joseph Campbell, “to give life meaning, to experience being alive, and to harmonize the microcosm of an individual with the macrocosm of the universal,” by which he means the invisible, overarching value structure or ‘codes of conduct’ within a society that connect it to certain metaphysical truths , the truths that individuals accept and promote as one’s “cultural operating system” (Campbell & Moyers, The Power of Myth).

Resource management is an increasingly important aspect of humanity’s cultural operating system. It appeared in the University of Cardiff in 1971 as an idea for a new interdisciplinary applied subject dealing with nature conservation. The notion came from a student/staff discussion. during a zoology field course on the Welsh National Nature Reserve of Skomer Island. The discussion originated within a group of students searching for a new cultural operating system and their story was one of dissatisfaction with the narrow view of world development and its economic system presented in single honours science subjects. These subjects had been formulated to serve 19th century empire builders. The student’s message was that modern society facing a deteriorating environment needed education for stewardship based on a natural capital account, not education for exploitation based on the asset stripping of nature to maintain year on year economic growth of a monetary economy.

Surprisingly, the idea was enthusiastically taken up by staff in the pure and applied science faculties as the philosophical thread for an honours interdisciplinary course in Environmental Studies. The new course was organised in Cardiff University during the 1970s. It integrated the inputs from eleven departments, spanning archaeology, through metallurgy, to zoology. Their contributions were organised around the theme of applied ecology as expressed in the organisation of natural resources for production of environmental goods and services . This interdisciplinary element amounted to one half of a general honours degree, the other half being the specialised syllabus of one of the contributing departments. Over the years it was chosen by many high grade students as an alternative to single honours.

Later in the decade this course was evaluated by a group of school teachers under the auspices of the University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate (UCCLES), from where it emerged as the interdisciplinary school subject ‘natural economy’. Natural economy was launched by UCCLES to fulfil their need for a cross-discipline arena to promote world development education. This project was initiated by the Duke of Edinburgh, Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. to bring environmental management to the centre of secondary school curricula. The title came from the 1980 World Conservation Strategy, which aimed to value natural assets as stocks in a natural capital account to develop and manage a country’s long term economic sustainably. In this context, ‘natural’ means derived from nature. As in natural law, ‘natural’ also means a belief in the existence of a rational and purposeful order to the universe. Therefore, as a guide to human endeavour, natural economy defines the actions necessary to live in accordance with this cosmic order, accepting the importance of monitoring and valuing natural assets to manage them for their sustainability. Therefore, natural economy as an educational theme is to the management natural resources for production as political economy is to the management of human resources for production.

Natural economy was launched by UCCLES as an international school subject and was also disseminated throughout Europe by the Economic Community’s Schools Olympus Broadcasting Association (SOBA) for distance learning.

Through a partnership between the University of Wales, the UK Government’s Overseas Development Administration and the World Wide Fund for Nature, natural economy was published as a central component of a cultural model of Nepal with the help of a sponsorship from British Petroleum.

During the 1980s, an interoperable version of natural economy for computer-assisted learning was produced in the Department of Zoology at Cardiff, with a grant from DG11 of the EC. This work was transferred to the Natural Economy Research Unit (NERU) set up in the National Museum of Wales towards the end of the decade.

Follow this link to an outline of an early natural economy framework

In the 1990s NERU obtained a series of grants to integrate natural economy into a broader cultural framework dealing with the relationships between culture and global ecosystems in which humankind is an evolving dominant species. For these purposes, cultural ecology was adopted as the holistic framework of an EC LIFE Environment programme with the aim of producing and testing a local conservation management system for industries and their community neighbourhoods. The R&D was carried out in partnership with the UK Conservation Management System Partnership (CMSP), the University of Ulster, four British industries and two european ones. The aim was to provide a web resource for education/training in conservation management in schools and their communities. The web resource developed as SCAN (Schools and Communities Agenda 21 Network) initiated by a post-Rio,1994 gathering of school teachers and academics in southwest Wales. The meeting was sponsored by the Countryside Council for Wales, Dyfed County Council, and the local Texaco oil refinery. This partnership was based in Dyfed’s St Clears Teacher Resource Centre. From here, a successful award-winning pilot was led by Pembrokeshire schools to create and evaluate a system of neighbourhood environmental appraisals, and network the local findings and action plans for improvements from school to school. The objective was to encourage schools to work with the communities they served, as out-of-school laboratories, to manage the community’s resources sustainably and so contribute to its Local Agenda 21 action plan.

Barriers to educational change

In 2015 Geoff Masters Chief Executive of the Australian Council for Educational Research “……argued that one of the biggest challenges faced in school education is to identify and develop the knowledge, skills and attributes required for life and work in the 21st Century. This is an ongoing curriculum challenge”.

In particular, he was questioning how well the school curriculum is preparing students for life and work in the 21st Century. He selected the following factors that were barriers to change.

- Current curricula often are dominated by substantial bodies of factual and procedural knowledge, at a time when it is increasingly important that students can apply deep understandings of key disciplinary concepts and principles to real-world problems.

- School subjects tend to be taught in isolation from each other, at a time when solutions to societal challenges and the nature of work are becoming increasingly cross-disciplinary.

- School curricula often emphasise passive, reproductive learning and the solution of standard problem types, at a time when there is a growing need to promote creativity and the ability to develop innovative solutions to entirely new problems.

- Assessment processes – especially in the senior secondary school – tend to provide information about subject achievement only, at a time when employers are seeking better information about students’ abilities to work in teams, use technology, communicate, solve problems and learn on the job.

- Students – especially in the senior secondary school – often learn in isolation and in competition with each other, at a time when workplaces are increasingly being organised around teamwork and are requiring good interpersonal and communication skills.

- School curricula tend to be designed for delivery in traditional classroom settings, at a time when new technologies are transforming how courses are delivered and learning takes place.

All of these six .barriers to educational innovation were responsible for the failure of natural economy and cultural ecology to gain traction as school subjects. The final blow in the UK came with the adoption of the national curriculum following the 1988 Education Reform Act.

Geoff Masters was writing in 2015 against the backdrop of a long-term decline in the ability of Australian 15-year-olds to apply what they are learning to everyday problems. Over the first twelve years of this century, Australian students completed their compulsory study of mathematics and science with declining levels of ‘literacy’ – that is, declining abilities to apply fundamental concepts and principles in real-world contexts. This decline is widespread and is evident in performances in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). .

In fact educationalists are still cleaving to the format that Cardiff students wished to overturn nearly half a century ago whereas society at large is being asked by the UN to commit itself culturaly to the 2030 millennium goals to live sustainably. This can only be achieved by global thrust towards education for sustainability at all levels.

It was only in 2012 that the UK’s Natural Capital Committee (NCC), was set up to report to the Government and advise on how to value nature to ensure England’s ‘natural wealth’ is managed efficiently and sustainably. During its first term it produced three reports to government on the ‘State of Natural Capital’. From this it appears that ecosystem assessment is beginning to influence economic thinking. Indeed it is a fundamental activity that is necessary if natural capital is to be mainstreamed within decision-making. It sends a strong signal to businesses and local decision makers but there have been no moves to integrate it with education for sustainability.

Since the 1970s changes in the environment surrounding our schools have been taking place rapidly against a backdrop of the shift from an industrial economy to one based on the instantaneous, global traffic of information. Today’s schools are still dominated by a national curriculum dating from Victorian values and its nonadaptive grip on teacher training. The pre-climate change national curriculum was not designed to prepare children for participation in the globally explosive knowledge economy or its demand for outcomes over process. The traditional model of teachers dispensing discrete, disconnected bodies of information, the traditional school subjects, presented in isolation from the other subject areas, is increasingly obsolete as a way to prepare children for living on a crowded planet. But for educators to simultaneously recognize these shifting dynamics, figure out how to address them through root and branch reform of instructional change, and then implement meaningful, sustainable changes, is a daunting task. Teachers and school leaders today must, as Tony Wagner puts it, “rebuild the airplane while they’re flying it” (Wagner, 2006).

This is why cultural ecology on line is now being accessed by millions but was squashed by the obligatory UK national curriculum shortly after its incarnation. Then it was greeted by Cambridge teachers with ‘How I wish I had been able to take it at school’. In fact the only country to adopt the Cambridge natural economy syllabus, top down, was Namibia, where it replaced the subjects of biology and geography.

Links

An important outcome was the production of an annotated mind map of cultural ecology starting with the idea of managing resources for a sustainable future. This mind map is still available as an educational exampler at the following web address: http://www.culturalecology.info/version2/ .

The following links set out the concept map derived from this mind map, which is augmented with connections to web sites providing more information about the concepts that are currently being expanded and augmented.

CULTURAL ECOLOGY

Because cultural ecology is an interdisciplinary educational subject there are many routes to establish a topic framework depending on the concept chosen to define the main idea. The following versions of cultural ecology are being developed within the system of Google-Sites.

CLICK Here for an updated version of this BLOG

Internet References

https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/bioregionalism-4e15f314327

http://lebendig.org/bioregion.htm#living

http://www.vedegylet.hu/okopolitika/Aberley%20-%20Interpreting%20Bioregionalism.pdf

https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/project-reports-and-reviews/the-ecology-of-culture/

http://isj.org.uk/illusions-of-world-ecology/

http://www.vedegylet.hu/okopolitika/Aberley%20-%20Interpreting%20Bioregionalism.pdf