“Meaning is the pairing of an idea with an object, an image, a thing. How could anything ‘mean’ something without us giving it meaning? And that meaning is completely relative. I don’t intend to say that we’re acting as some supreme meaning-creator. But, humans with their human minds, they search for meaning – they try to find meaning in everything. Does it have meaning? Does anything? We seek to understand patterns so out of the chaos of life we find patterns which offer some comfort, some sense of identity, some rhythm and, out of that, create a sense of identity. Hopefully we find patterns and meaning that help us to lead healthier, happier, more loving lives” Michael Divine

http://realitysandwich.com/222172/conversation-michael-divine-lily-kay-ross/

The Land Ethic

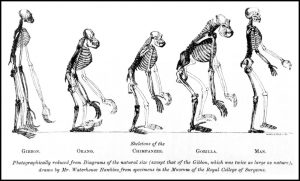

Fig 1 Comparisons of the human skeleton with those of apes.

In 1863, eight years before Darwin’s Descent of Man, Thomas Henry Huxley published his most famous work, Evidence as to Man’s place in Nature. He pointed out the anatomical similarity of humans and apes, particularly regarding their brains, which underpinned Darwin’s case for their common ancestry. Huxley drew attention to the biological unity of apes and humans, implying that humankind was, and still is, an integral part of nature.

Eight decades passed amidst a growing concern about the speed and impact of industrialization on the natural world and human-nature relationships. This period saw the rise of the conservation movement. Human agency in the modern world is profoundly shaped by the economics of industrialism. It was becoming obvious that in order to address environmental degradation world leaders would sooner or later have to come to terms with the premises and consequences of an economics that supported the endless growth of mass production Growth-economics did not have a satisfactory way of handling environmental concepts like wilderness or beauty and Aldo Leopold encapsulated this issue in his 1947 essay, “The Land Ethic,” which would eventually be published in A Sand County Almanac in 1949. For Leopold, human action in the environment is dictated by an economic system based on a utilitarian attitude towards land which is as economically illiterate as it is morally unsustainable. He traced this non adaptive way of thinking back to the Judeo-Christian tradition, noting that,

“for twenty centuries and longer, all civilized thought has rested upon one basic premise: that it is the destiny of man to exploit and enslave the earth. The biblical injunction to ‘go forth and multiply’ is merely one of many dogmas that imply this attitude of philosophical imperialism.”

In the Sand County Almanac he wrote,

”It is a century now since Darwin gave us the first glimpse of the origin of species. We know now what was unknown to all the previous caravan of generations: that men are only fellow voyagers with other creatures in the odyssey of evolution. This new knowledge should have given us, by this time, a sense of kinship with other creatures; a wish to live and let live; a sense of wonder over the magnitude and duration of the biotic enterprise”.

At issue here is how the worldview of Western civilization has been deeply scarred by what Leopold has described as a conqueror mentality towards land. However, this worldview was becoming increasingly untenable in view of human population growth, the increased power and efficacy of human technology, and ecological findings which defined the land as a close knit living community.

Conservation was a response to an overly simplistic economic worldview, but its success, Leopold realized, would depend on whether society was able to revise this worldview to bring human consumption in line with its planetary limits. The dominant economic worldview would need to be reconciled with a global ecological understanding and ethical treatment of what we now call the biosphere. At the heart of Leopold’s conservation thinking was an emphasis on the importance of personal stewardship on the part of private landowners that would be ultimately based on values and beliefs that defy pressure of growth-economics. In his essay he proposed that human beings view themselves as “plain members and citizens” of the living community of the land and not as its conquerors. He then proposed that economic expediency be supplemented, perhaps even preceded, by other considerations:

“quit thinking about decent land-use as solely an economic problem. Examine each question in terms of what is ethically and esthetically right, as well as what is economically expedient. A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Writing in 1949, he noted,

“it seems likely that the present muddle (in the pursuit of conservation through public ownership of land) arises from the fact that the conservation problem involves a new category of economic phenomena; one with which economists are accustomed to deal.”

Zen and Ecology

We still await the international adoption of Leopold’s new category of economic phenomena, which is now known as steady state economics aimed at sustainable development. In the meantime there has been a shift towards changing human attitudes to nature with humankind being viewed as an integral part of the biosphere in everything it does.

This idea is central to Zen, a Buddhists philosophy which appeared with the youth culture in the West, during the 1950s. Zen became an adjective to describe any spontaneous or free-form activity concerned with seeing observing and searching to generate mindfulness. For Buddhists there is no self in the deep sense that no one exists as a singular, permanent structure distinct and isolated in any meaningful way from the rest of the world. This is entirely in line with an evolutionary and ecological approach to our origins and our embeddedness in natural processes.

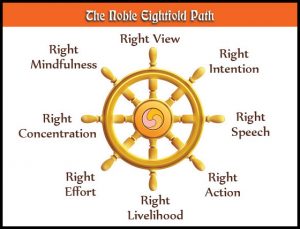

Fig 2 The noble eightfold path of Buddhism to achieve a state of mindfulness

The word Zen is derived from the Chinese word “chán” and the sanskrit word “dhyana,” which mean “meditation.” In sanskrit, the root meaning is “to see, to observe, to search.” In this respect, the combined behaviours of seeing, observing and searching as a spiritual process by which to gain knowledge of our place in nature pre date the invention of Buddhism.

It is in this vein that David Barash published an article in 1973 entitled “The Ecologist as Zen Master” in which he discussed what he considered the remarkable parallels between Zen Buddhism and the then emerging public writings on ecology. He felt that the interdependence and unity of all things was fundamental to both Zen practice and the science of ecology. In addition, both share a common non-dualistic view of the fundamental identity of humankind and its surroundings. A bison cannot be understood in isolation from the prairie; understanding requires study of the bison-prairie unit. He concluded that “the very study of ecology, is the elaboration of Zen’s nondualistic thinking”.

This nondualistic thinking was taken up practically in 1991 on the eve of the first meeting of world leaders to produce an agenda for sustainable development by John Seed, director of the Rainforest Information Centre in Australia. He gave the following answer to the question of how he deals with the despair of difficulties associated with saving the remaining rainforest:

“I try to remember that it’s not me, John Seed, trying to protect the rainforest. Rather I’m part of the rainforest protecting myself. I am that part of the rainforest recently emerged into human thinking”

Environmental Mindfulness

Zenists act to develop the realization that self and world are not separate. This development in the context of Buddhism takes place through meditation and the cultivation of mindfulness. The mental exercise known as meditation is found in all religious systems. Prayer is a form of discursive meditation, and in Hinduism the reciting of slokas and mantras is employed to tranquilize the mind to a state of receptivity. Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh offered the following guidance regarding the goal of meditation on humankind’s fears and hopes for Earth in 1991.

“If we want to continue to enjoy our rivers—to swim in them, walk beside them, even drink their water—we have to adopt the non-dual perspective. We have to meditate on being the rivers so that we can experience within ourselves the fears and hopes of the river. If we cannot feel the rivers, the mountains, the air, the animals, and other people from within their own perspective, the rivers will die and we will lose our chance for peace”.

In the early 1990s, both John Seed and Thich Nhat Hanh were part of an international movement promoting the need to develop a deeper level of environmental understanding so that people can act environmentally out of “feeling” or experience, rather than intellectual knowledge. David Orr in 1994 discusses the importance of “feeling” the truth. In the final chapter to his book, Earth in Mind, he concludes that the objective of environmental education should be to draw out our affinity for life. Orr believes we cannot act wisely without knowledge. We will not act wisely without feeling. The cultivation of mindfulness is a time honoured Buddhist method to develop such feelings. Mindfulness is a sharpened awareness of the immediate present in which we strive to look deeply into the environmental impact and value of our every action. The latter aspect was taken up by the Zen teacher Philip Kapleau in his book The Three Pillars of Zen in 1965. It was one of the first English-language books to present Zen Buddhism not as philosophy, but as a pragmatic and salutary way of training and living:

“It is precisely the lack of mindfulness that is responsible for so much of the violence and suffering in the world today. … The aware person sees the indivisibility of existence, the deep complexity and interrelationship of all life, and this creates in him a deep respect for the absolute value of things” .

One Square Foot of Earth

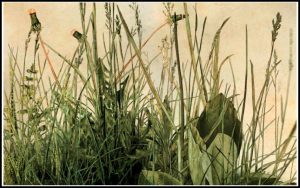

Fig 3 Whispering Weeds, Mat Collishaw

James Thornton’s book, ‘Radical Confidence: A Field Guide to the Soul’, was published in 1997. James was a top US litigator for the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), winning over 100 federal cases. Yet he came to feel that the tools he was using as a litigator and environmental advocate “were used up.” He felt that beyond the changes in policy he could effect as a lawyer, a shift in consciousness on the cultural level was needed because so much of his work was based on anger. This was a kind of righteous anger, what any person feels when they look at what our society is doing to the Earth. He had to admit to himself that he hadn’t gone beyond anger. His book was a call to go deeper, to explore ways of working, living, and being beyond those of the lives we create for ourselves. Some of us answer that call and are brought into new ways of seeing, gaining insights that allow for an opening of the heart, mind, and soul. James Thornton is such a person. He began by questioning what the impact would be if everything he and other environmental activists were advocating was put in place, which is unlikely because of the way the political system works, would that be enough? Would they then be in a sustainable and harmonious relationship with the Earth? Thornton’s answer was absolutely not. The environmentalists knew they were dealing in the realm of real politics and the types of large scale changes they would like to see were the ones they could not even advocate because of the political realities and the consciousness at play in politics. Genuinely fundamental changes were ones that required a metamorphosis in individual consciousness. Is there a way in which Buddhist practice and other contemplative practices can contribute toward healing the alienation that has divided us from the Earth, our thoughts from our bodies, and us from other species?

Thornton’s own sense was that some kind of contemplative practice, and it can be from a Christian tradition, a Hindu tradition, a Jewish tradition, or Buddhist tradition, is absolutely required to bring about such a metamorphosis. Simply being in the space of quiet mind in the natural setting and allowing the heart to speak allows a surprisingly rapid experience of intimacy with the Earth. He illustrated this with the following story from a class where he was teaching the practical way to achieve a state of environmental mindfulness.

The instruction was to sit concentrating on one square foot of earth and simply be with it for an hour. The hope was that by paying total awareness to one square foot of Earth, you are experiencing in the natural world what you do contemplatively when you give total awareness to the inner world, which he called the “inscape.”

One woman came back and related how she had sat with her square foot of earth which was full of grass. It took twenty minutes for her to quiet down to the point where she noticed a small caterpillar that she had in fact been looking at for twenty minutes. She remembered the instructions that if a question was coming up from your heart, to simply allow it to come and in fact to direct it to the living organisms that you were sitting with. Out of her heart rose the question for the caterpillar: “will you teach me about metamorphosis?”

The caterpillar responded rather like a tough old Zen master: “Why should I teach you about metamorphosis?” She answered, “because you will be going through complete metamorphosis and turn into a butterfly – who better to teach me about how to change?” The caterpillar said, “you don’t seem to understand, most of us don’t make it to butterflies. Either we don’t find the right food plants and die or we’re eaten by predators. There’s no guarantee at all that I’ll become a butterfly. On the other hand, you, as a human being, experience metamorphosis all the time. If you want to know about metamorphosis, study yourself.”

She was speaking with her larger self, represented by Earth, opening her mind in a way that transformed her, and in a way that was very gentle and very subtle, to feel a sense of connection to the larger world, to the cosmos.

Thornton expanded on this as follows:

Simply opening produces healing. When a person, as that young woman did, opens to that part of us, that which needs healing the most comes forward. There is a very gentle progression of material that emerges when we begin opening in this way, so that the things that would overwhelm us don’t come up and things that need to be healed, that we can in fact deal with, are what come up first. Progressively deeper material comes up.

Part of my intensely deep practice in Germany was walking for several hours a day in the woods that surrounded the town. It was an integral part of the meditation. I began to think that meditation or contemplative practice that is divorced from the world is a little bit crazy. These practices in fact tend to have been developed in the natural world. Buddha sat under a bodhi tree. Jesus wandered and fasted in the desert. All of these practices are very deep in their origin, with a very deep connection with the Earth. You open so much that the Earth then teaches – the wisdom encoded in nature simply speaks. It’s wonderful to meditate in a hall or to pray in a church – it’s fabulous. But if that’s the only place we do it, we’re actually missing what the practices originally gave people when they were founded.

At a time when people are desperate to make some sense of their lives, Thornton demonstrates how to embark on our own hero’s journey. Only by taking full responsibility for our thoughts, feelings, and actions can we bring about the revolution in consciousness that is so vital today. In order to discover how to care for the Earth and all its inhabitants, we must first learn how to care for ourselves. Thornton shows us the way. He leads us through a series of contemplative exercises designed to clarify the body, mind, and heart, and make a deep connection with the wisdom encoded in the natural world. His nature writing is joyously lyrical; the book as a whole is immensely practical, drawing on Jungian psychology, and Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian teachings, to give people the tools to work for the benefit of all living beings. A Field Guide to the Soul has been described as “the Bible for the new millennium.”

Inscape and Instress

The term inscape used above by Thornton was coined by the Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins as he developed his theories of what constituted poetry. ‘Inscape’ means the particular features of a certain landscape or other natural structure, which make it different from any other. Hopkins, as a poet-artist, had to determine just what was special about any scene. His notebooks show the tremendous care with which he details what he thinks is unique about a particular sunset, cloud formation or even waves. He invented the term ‘instress’ to mean the actual experience a reader has of inscape: how it is received into the sight, memory and imagination. The poet’s job is to find images that will ‘nail’ the inscape down for readers, so they can recapture the poet’s perception and experience.

The terms convey the uniqueness of each created thing or person, and how that individuality is perceived or experienced by the observer. Hopkins felt it was the artist’s job to perceive and express such uniqueness, either in art or through words. He constantly attempted this in his journals and letters.

All this suggests the need for contemplation to understand what one is seeing. William Wordsworth experienced a similar inscape frequently in his time of living in the Lake District or in his travels. He called the particular intense experiences he had of a landscape ‘spots of time’, and as patterns in nature they had definite spiritual or mystical significance for him. When we say ‘landscape’, that does not exclude people, as they too have their own inscape. Such experiences confirmed for Wordsworth the presence of some spiritual entity beneath the surface of reality, and the instress was, as it were, a veil being briefly withdrawn, so that he could perceive this.

Fig 4 Five actions of mindfulness

The whole Romantic enterprise was to see nature in its individuality, as opposed to the scientific approach of the eighteenth century, which had been to classify and generalise. With today’s technology, we can see each snowflake as being different, have our fingerprints taken and our DNA profiled to establish our uniqueness. So there now is less clash between the impersonality of science and the intense individuality of the microcosms of Romanticism.

Around this time, another key writing on this behavioural zenic theme appeared. Entitled The Conservation Biologist as a Zen Student, it was published in 1997 by Fred W. Allendorf. According to Allendorf the primary issue of environmentalism is that we behave in a way we believe benefits ourselves at the expense of nature. This is true both at a collective level (jobs versus the environment) and an individual level (driving a car versus riding a bike). However, Allendorf says this perception of a “choice” is incorrect because humans are not separate from nature. In other words Zen is not about concepts or ideas; it is about how we live our lives. Zen can play a practical role in providing guidance for the conservation biologist in his or her life. Many of the principles considered here are found in most Buddhist teachings, not just Zen.

Alllendorf’s paper was published in the journal of the Society for Conservation Biology. The goal of the Society, as stated in every issue of its journal, is “to help develop the scientific and technical means for the protection, maintenance, and restoration of life on this planet”. However, Allendorf’s view, like that of Thornton, is that the lesson of Zen is that knowledge alone of what needs to be done is not sufficient to change our behaviour . For example, Allendorf says we turn light-switches on many times throughout our daily life without awareness. Mindfully performing this act requires awareness of the physical sensation of touching and moving the switch. In addition, we become aware of the effects of this action.

I live in a power-grid connected to the power generating dams of the Columbia River. The connection made when I turned the switch in my office this morning connected my computer with electrical power generated by dams on the Columbia River. These dams and the long pools behind them have blocked or hindered the return of salmon to their spawning grounds. I try to be aware of that connection every time I turn on a light switch; I usually fail.

Environmental awareness can be reinforced by gathas. These are short verses used to bring the energy of mindfulness to each act of daily life and are a traditional form of Zen practice. The following gatha, written by Thich Nhat Hanh in 1992, can be used before every meal:

In this food,

I see clearly the existence

of the entire universe,

supporting my existence.

Another of Allendorfs everyday examples of stimulating mindfulness is seeing the entire universe in our breakfast cereal.

If we take just a moment to reflect, “the ocean is there; the rain that watered the grain was carried from the ocean by clouds. The sun is there; the grain could not grow without energy from the sun. The Jurassic ecosystem in which the dinosaurs dwelled is there; plants that fed the dinosaurs 200 million years ago were transformed into the fossil fuel that was used to harvest the grain and to carry it to the table. Gregor Mendel is there, along with the plant breeders who developed the strains of grain. Such moments of reflection strengthen our appreciation of our interdependence to countless beings, past and present, near and far”.

Cultivating such constant awareness of our actions is a powerful method to transform our behaviour so that we can act in a way that will protect, maintain, and restore life on Earth. The stated goal of the Society for Conservation Biology is to save “life on this planet”. However, Zen teaches that we cannot save others; at best, we can save ourselves by transforming our own unskillful ways. However, Zen also teaches that our identity is not limited to our ego-self. Our identity includes all living beings. Humans act in a way that they feel is in their own self interest. We will act to save “life on this planet” only if we recognize at a deep level that our “self” includes all beings. We need to recognize and feel at a deep level that ultimately we are not conservation biologists trying to save other species. Rather, we are one emergence of life on this planet trying to save itself.

Fig 5 Small Wood

Roots of Zenic Behaviour

To most people, Zen is associated with meditation, and is seen as being beyond their experience. In the West, during the 1950s, Zen became an adjective to describe any spontaneous or free-form activity concerned with seeing, observing and searching to generate mindfulness. Strictly speaking Zen is a noun. Zenic is an adjective. The aim of these zenic behaviors is to encourage logical thinkers to become logical and poetic thinkers. While the discernment of rational thought is not lost, the complementary zenic perspective of a poetic and spiritual sensibility towards self and environment is added.

The roots of zenic behaviour are:

1 Let go of what you can’t control. You are the only entity that you can fully control. Your thoughts, actions and feelings are what you are able to change. The actions and thoughts of anyone else, on the other hand, are precisely what you cannot control, perhaps despite your best efforts. Learn to let go of what other people think and do, and turn your focus back onto yourself.

- Give people the benefit of the doubt. If you think you’ve been wronged or mistreated, evaluate the situation from a third-person point of view. Consider that the offending person might not be aware of what they’ve done. Give them the benefit of the doubt and consider they are just unaware.

- Alternately, if someone has disappointed you, think about your expectations. Are they realistic? Were your expectations communicated to the other person? It might help to talk to that person, for example, to clarify how the miscommunication happened.

2 Look at the bigger picture. Putting things into perspective will help you balance the way you approach life. This goes hand in hand with letting go of things you can’t control. Ask yourself what else is happening in the world that might be contributing to a negative situation.

- When thinking about an issue that you can’t control, make a list of factors out of your control that impact this issue. For example, if you are having trouble finding a job, think about the downturned economy or the outsourcing of jobs in your industry.

- Reduce worry by asking yourself if something will matter in an hour or a day from now.]

3 Control or change the aspects that you can control. When you empower yourself to take control of certain things, you can feel more adept at maintaining a calm attitude.

- For example, if you get riled up at the morning traffic, consider controlling your interactions with the traffic by changing the time that you leave in the morning, or taking mass transit.] Don’t give your mind more fodder for stress, anger and frustration. Instead, reduce these things so you can clear your mind.

Zen Buddhists following Thich Nhat Hanh take 14 precepts or what we might call vows. Three of these have relevance to the practical applications of zenic thinking:

- Precept 5: do not accumulate wealth while millions are hungry. Do not take as the aim of your life fame, profit, wealth, or sensual pleasure. Live simply and share time energy and material resources with those who are in need.

- Precept 11: do not live with a vocation that is harmful to humans and nature. Do not invest in companies that deprive others of their chance to live. Select a vocation that helps realise your ideal of compassion. (Thinking of business as a vocation may well shift the consciousness of those involved in it. Taken with precept 5 business becomes a sustainable vehicle for the zenic purpose to be realised in the hearts of individuals working in business.)

- Precept 13: possess nothing that should belong to others. Respect the property of others, but prevent others from profiting from human suffering of other species on earth. (This calls us to make very certain that the activities of business are non grasping and that where we find this to be happening that we speak out against it.)

Buddhist practice is deeply concerned with discarding beliefs that exist that give rise to suffering. This means discarding:

- believing oneself to be separate from others

- believing that the environment is a resource to be used in unlimited ways

- believing that material wealth makes us happy

- believing that the suffering of communities different from our own has nothing to do with us

- believing that what we do makes no difference

- believing that the systems and structures we have created are the only ones we can make work

- not understanding that impermanence is built into everything we do.

These can be taken as markers on the way to sustainability.

Natural Contemplation

Thomas Merton, the great twentieth century monastic Christian contemplative, once wrote that one of the biggest challenges facing his novices was their lack of “natural contemplation,” the contemplation of nature. Teaching people about proper disposal of garbage, recycling, and other environmental topics is not the answer. People only protect what they love. To love something, you have to know it. But what does “knowing” entail? As world populations continue to rise and as wild spaces are reduced due to human encroachments, our heightened interactions with other beings expand our awareness of both ourselves and other. As individuals, our consciousness of the boundaries between humans and other living things ultimately determines our own fate as a species. Having become dependent on other species, plants, animals and microbes, for psychological and nutritional needs, human beings don’t often know where the self ends and the other begins.

Many scholars have ventured general comparisons of Eastern and Western Art. Suzuki (1957:30) suggests that Oriental art depicts spirit, while Western art depicts form. Watts (1957:174) holds that the West sees and depicts nature in terms of man-made symmetries and super imposed forms, squeezing nature to fit his own ideas, while the East accepts the object as is, and presents it for what it is, not what the artist thinks it means. Gulick puts it this way:

Oriental artists are not interested in a photographic representation of an object but in interpreting its spirits . . . . Occidental art . . . exalts personality, is anthropocentric . . . . Oriental art . . . has been cosmocentric. It sees man as an integral part of nature . . . . The affinity between man and nature was what impressed Oriental artists rather than their contrast, as in the West. To Occidentals, the physical world was an objective reality–to be analyzed, used, mastered. To Orientals, on the contrary, it was a realm of beauty to be admired, but also of mystery and illusion to be pictured by poets, explained by mythmakers, and mollified by priestly incantations. This contrast between East and West had incalculable influence on their respective arts, as well as on their philosophies and religions. (1963:253-255).

One of the richest visual objects in Tibetan Buddhism is the mandala. A mandala is a symbolic picture of the universe. It can be a painting on a wall or scroll, created in coloured sands on a table, or a visualisation in the mind of a very skilled adept.

Fig 6 Thangka painting of Manjuvajra Mandala

A similar spirit pervades the Zen haiku – a poem in seventeen syllables that must point to a certain wholeness of perception. The poet’s skill is judged by his imperceptibility in the haiku, which must capture the essence of the moment in which it is conceived and written.

An example of a famous haiku by thep Zen master Basho:

An ancient pond

A frog jumps in

Plop!

Another one, also by Basho:

You light the fire

I’ll show you something nice –

A great ball of snow!

Haiku of a quiet, desolate sabi-laden moment by Gochiku:

On a withered branch

A crow is perched,

In the autumn evening.

http://homepages.sover.net/~chughes/jlc/essays/crisis.html

http://www.inkdancechinesepaintings.com/chinese-chrysanthemum-paintings.html

Intercultural Zenic Art:

https://terebess.hu/zen/sengai.html

“Resting the mind can be accomplished by meditation, and also by artwork, which allows the intuition to flow: the conscious mind recedes. Meditation and art work at their best complement each other, and true things emerge.” —Candace Loheed

Zen means “meditation.” Zen teaches that enlightenment is achieved through the profound realization that one is an enlightened being. This awakening can happen gradually or in a flash of insight. But in either case, it is the result of one’s own efforts. Deities and scriptures can offer only limited assistance. Enlightenment, the essence of Zen, is a freedom of thinking that is in, but not of this world and does not require anything extraneous.

Zen Buddhism’s emphasis on simplicity and the importance of the natural world generate a distinctive aesthetic, which is expressed by the terms wabi and sabi. In traditional Japanese aesthetics, Wabi-sabi is a world view centred on the acceptance of transience and imperfection. The aesthetic is sometimes described as one of beauty that is “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete”. It is a concept derived from the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence, specifically impermanence, suffering and absence of a well reasoned self-nature. Self-nature, strictly defined, is the totality of our beliefs, preferences, opinions and attitudes organized in a systematic manner, towards our personal existence. Simply put, it is how we think of ourselves as an individual. In meditation we compare our present selves with the self we should be and if there if they do not march up with how we should think, behave and act out our various life roles, then try to discover ways of making the change.

Characteristics of the wabi-sabi that are guides to the zenic art aesthetic include asymmetry, roughness, simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty, intimacy, and appreciation of the ingenuous integrity of natural objects and processes. These two amorphous concepts are used to express a sense of rusticity, melancholy, loneliness, naturalness, and age, so that a misshapen, worn peasant’s jar is considered more beautiful than a pristine, carefully crafted dish. While the latter pleases the senses, the former stimulates the mind and emotions to contemplate the essence of reality. In today’s Japan, the meaning of wabi-sabi is often condensed to “wisdom in natural simplicity.” In art books, it is typically defined as “flawed beauty.”

Fig 7 “Fujisan” white Raku ware tea bowl (chawan) by Honami Kōetsu, Edo period

Whether she is a Buddhist or not the zenic artist strives to apply Wabi-sabi to illustrate the inherent nature of an aesthetic object by the simplest means possible. The goal is to capture the intrinsic qualities of the object, its eternal essence. Contemplation is key to the creation and viewing of art, as it requires a deep personal understanding of the inner nature of the subject being rendered and viewed.

Art in the West has developed a complex linguistic symbolism through which the artist manipulates his material to communicate something to his audience. Art as communication is basic to Western aesthetics, as is interrelationship of form and content. Music is considered a language of feeling and consists of sonorous moving forms. Landscape painting in the Western tradition is not merely an aesthetically pleasing reproduction; the artist uses his techniques of balance, perspective, and colour, to express a personal reaction to the landscape–his painting is a frozen human mood. The aesthetic object is used as a link between the audience and the artist’s feelings and the Western artist’s technique is used to create an illusion of the forms of reality.

The zenic artist, on the other hand, tries to suggest by the simplest possible means the inherent nature of the aesthetic object. Anything may be painted, or expressed in poetry, and any sounds may become music. The job of the artist is to suggest the essence, the eternal qualities of the object, which is in itself a work of natural art before the artist arrives on the scene. In order to achieve this, the artist must fully understand the inner nature of the aesthetic object. The latter is its Buddha nature. This is the hard part. Technique, though important, is useless without it; and the actual execution of the artwork may be startlingly spontaneous, once the artist has comprehended the essence of his subject.

The style of painting favoured by traditional Zen artists makes use of a horsehair brush, black ink, and either paper or silk. It is known as sumi-e. A great economy of means is necessary to express the purity and simplicity of the eternal nature of the subject, Because it is a generalizing factor, Zen art does not try to create the illusion of reality. It abandons true to life perspective, and works with artificial space relations which make one think beyond reality into the essence of reality. This concept of essence as opposed to illusion is basic to Zen art in all phases.

Fig 8 The Emperor’s goat

A favourite example of the creative working of a zenic artist is the story of the Emperor’s goat. A Chinese painter was once commissioned to paint the Emperor’s favourite goat. The artist asked for the goat, that he might study it. After two years the Emperor, growing impatient, asked for the return of the goat; the artist obliged. Then the Emperor asked about the painting. The artist confessed that he had not yet made one, and taking an ink brush he drew eight nonchalant strokes, creating the most perfect goat in the annals of zen Chinese painting.

The earliest reference to Zen brushwork occurs in the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, a text which relates the life and teaching of the illustrious Chinese master Hui-neng (638-713). Buddhist scenes, composed in accordance to canonical dictates, were to be painted on the walls of the monastery in which Huineng was labouring as a lay monk. At midnight the chief priest sneaked into the hall and brushed a Buddhist verse on the white wall. After viewing the calligraphy the next morning, the abbot dismissed the commissioned artist with these words: “I’ve decided not to have the walls painted after all. As the Diamond Sutra states ‘All images everywhere are unreal and false.”‘ Evidently fearing that his disciples would adhere too closely to the realistic pictures, the abbot thought a stark verse in black ink set against a white wall better suited to awaken the mind.

Thereafter, art was used by Chinese and Japanese Buddhists to reveal the essence, rather than merely the form of things, through the use of bold lines, abbreviated brushwork, and dynamic imagery—a unique genre now known as Zen art.

Although the seeds of Zen painting and calligraphy were sown in China, this art form attained full flower in Japan. Masterpieces of Chinese Ch’an (Zen) art by such monks were enthusiastically imported to Japan during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and a number of native artists studied on the mainland. Building on that base, Japanese monks produced splendid examples of classical Zen art; eventually Zenga became one of the most important Japanese art forms, appreciated the world over for its originality and distinctive flavour.

Early Zen in Japan was a religion for cultured aristocrats and powerful lords but by the fifteenth century Zen priests and nuns became actively concerned with the welfare of common folk. The democratization of Zen had a marked effect on painting and calligraphy, and the scope of Zen art was dramatically expanded.

Hakuin and Sengai, the two greatest Zen artists, employed painting and calligraphy as visual sermons (eseppo) to teach the hundreds of people, high and low, that gathered around them. Both of the masters drew inspiration from other schools of Buddhism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Taoism, folk religion, and scenes from everyday life; their calligraphy too embraced much more than quotes from the Sutras and Patriarchs—nursery rhymes, popular ballads, satirical verse, even bawdy songs from the red-light districts could convey Buddhist truths. Zen art thus became all-inclusive: anything could be the subject of a visual sermon.

Following the example of Hakuin and Sengai it became de rigueur for Zen masters to do much of their teaching through the medium of brush and ink; a tradition that continues to the present day. In many ways, Japanese Zen art parallels the Tibetan Buddhist concept of termas (hidden treasures).

According to Tibetan legends, the guru Padmasambhava hid thousands of texts all over the country to be discovered later when the time was ripe for their propagation. Whether or not this is literally true, during the persecution of Buddhism in Tibet during the ninth century, a large number of religious texts and articles were in fact hidden in caves, under rocks, inside walls, and other secret places to prevent their destruction, and over the centuries such treasures were gradually recovered. Similarly in Japan during this century, devotees of Zen art have uncovered thousands of magnificent pieces locked away in temple store-rooms, sitting forgotten on shelves in private homes, kept in drawers by indifferent art dealers, or left uncatalogued in museums. The illustrations in this article are largely comprised of such discoveries. Significantly, these pieces, some unseen for centuries but still bearing a message as fresh and forceful as when first delivered, are reappearing just as it is possible to display them throughout the world by means of modern print technology.

While the primary purpose of Zen painting and calligraphy is to instruct and inspire, it does have a special set of aesthetic principles; indeed, the best Zen art is true, beneficial, and beautiful a combination of deep insight and superior technique. The freshness, directness, and liveliness of Zen painting and calligraphy imbue it with a charm that few devotees of Japanese art can resist.

Belief in the superiority of spiritual mastery over technical mastery is evidenced by numerous stories of Japanese sword fighting in which untrained monks defeated trained samurai because they naturally comprehended the basic nature of the contest, and had no fear of death whatsoever..

One aspect of Zen thought and practice that is important to understand is how much it is a reaction against the popular culture and ideology of the times, both then and now. Zen spontaneity evolved out of dissatisfaction with stale tradition and dominant social structures. Zen, therefore, is almost always a rebellion against political, artistic, and social forms that threaten to crush natural action and true human feeling. Jazz, too, continues to react against structures, whether the tightly set chord patterns of popular music or the idea of musicians as entertainers only. Jazz rebels against the concept of music as a pre-set, pre-determined form, and, like Zen, demands that people act purely in the moment, without reference to past learning or future anxieties.

Like painting, poetry and other cultural expressions of Zen, jazz could be said to be the practice of a set of musical theories. Jazz musicians, like Zen practitioners, though, always take their theory with a high degree of scepticism. That is, theorizing in abstract ways tends to move away from concrete realities, and often ends up in hollow music. In Zen gardens, the mind is always brought back to the rocks, plants and walls of the garden whenever the mind starts to float away into transcendent formulas or abstract musings. In jazz performance, the musician too is constantly brought back to the concrete sounds, rhythms, and tones of music. Jazz, though, is rarely an individual practice, but also incorporates the concrete expressions of the jazz performance, the musician too is constantly brought back to the concrete sounds, rhythms, and tones of music. Jazz, though, is rarely an individual practice, but also incorporates the concrete expressions of the other musicians. In these ways, the abstract is not shunned, but not invited in, either. In the best of jazz and of Zen, the concrete and the abstract work together as a single, unified force.

Spontaneity is at the core of both jazz and Zen. The overlaps and parallels are hard to other musicians. In these ways, the abstract is not shunned, but not invited in, either. In the best of jazz and of Zen, the concrete and the abstract work together as a single, unified force.

Objects and Subjects for Meditation

All the 7 billion people of the world have only one single Planet where we can live and perpetuate, and that is our precious Mother Earth. The rate at which we extract natural resources far exceeds their rate of natural replenishment by natural biological and physical processes. Earth is giving us signs and warnings that ‘business as usual’ will not do. We are NOT taking heed of the critical signs because we are too busy running our daily lives in a competitive world where increasing material wealth is seen as good and right. But the sad fact is that there is no social equity in the quest for sustainable development. We are really not bothered about other human beings who are far more disadvantaged than us in the social and economic perspectives. Members of the same human race do not care for one another! M. Nadarajah

http://arecabooks.com/product/living-pathways-meditations-sustainable-cultures-cosmologies-asia/

Object focused meditation is a visual meditation involving an external physical item. We are conditioned to be task-oriented since childhood, so we have learned to keep the mind from drifting by giving it a task to focus on.

Object focused meditation makes use of this conditioning by getting the mind to focus on the object in front of you. It tricks the mind into staying in the present moment. The nature of the specific physical item to use for the meditation is a matter of personal preference and anything from a candle flame to a picture of a deity to a flower to a rock could be used. The external object of attention is useful in as much as it acts as a point of reference to which the mind can easily be tethered. Every time it strays, you simply need to bring it back to the object. However, if the meditation is aimed at getting a deeper understanding of the natural world it helps to choose an object that is natural.

The chosen object should meet two conditions –

- be small enough so it can be scrutinized without having to move your head, and

- be big enough so you don’t have to strain your eyes to study its details

Regarding the subjects for meditation, the most important points of focus are the pathways between culture and ecology that have to be followed in order to live sustainably. Cultural ecology on Earth today is dominated by unmindful production and consumption. We consume to forget our worries and our anxieties. Tranquilising ourselves with over- consumption is not the way. The objective of zenic meditation is to learn how to live mindfully and cooperatively, in harmony with others and with nature. The route map was plotted on September 25th 2015 when countries adopted a set of goals to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all as part of a new sustainable development agenda. Each goal has specific targets to be achieved over the next 13 years. For the goals to be reached, everyone needs to do their part by adopting behaviours in keeping with the new sustainable development agenda: governments, the private sector, civil society and ordinary people.

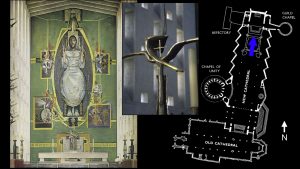

Meditation on the Coventry Tapestry

Fig 9 The Great Tapestry at Coventry Cathedral

As an educational example of meditative education the theme of ‘Notions About Nature’ or ‘Seeking Spiritual Signs in the Living World’ was taken in the 1990s as a response to the Rio Environment Summit which involved establishing a communal network for meditation on notions about nature: part of the Welsh Schools in Communities Agenda 21 Network (SCAN)

The collective meditation began with the industrial assault of the Sea Empress oil spill on an exceptionally beautiful Welsh coastline that had been a source of spiritual inspiration for the painter Graham Sutherland. Groups of children were activated to follow Sutherland’s particular notional language; a quest which led inevitably to his Great Tapestry in Coventry Cathedral.

It is presented on the web to other students for comment, and in the hope that it will be extended with other local appraisals of the ‘sacredness of place’.

The first version was edited from the contributions of Welsh students who have participated in real, and virtual, discussion groups within the Schools in Communities Agenda 21 Network SCAN organised from the National Museum of Wales Cardiff (1996- 99)

A spiritual view of environment emerges from trying to read and express various signs of the workings of nature in relation to our position in the grand scheme of things. For example, the Koran has much to say about ‘signs’ which, through the imagination, point to the deeper significance of everyday life.

‘In the creation of the heavens and the earth; in the alternation of night and day; in the ships that sail the ocean with cargoes beneficial to man; in the water which God sends down from the sky and with which He revives the earth after its death, dispersing over it all manner of beasts; in the disposal of the winds, and in the clouds that are driven between earth and sky; surely there are signs for rational men (The Koran 2:163).

With a similar set of holistic notions about nature, St Francis of Assisi praised God ‘for our sister, Mother Earth, which brings forth varied fruits and grass and glowing flowers’, and ended with praise to God ‘for our Sister the death of the body’. Neighbourliness on the part of a stranger is signed as a cultural element of evolved human behaviour in the parable of the good Samaritan. A sunset seen above an urban skyline can be both a scientific and an uplifting spiritual experience. These cultural notions about nature cemented families to neighbourhood in the past, but are now lost or diluted within our urban and rural placeless subcultures. Individuals and families lie unattached to the major world religions and are left to develop their place in an idiosyncratic cosmology.

Moral and spiritual teaching has always relied heavily on visual imagery. Images make and realise a society’s attitudes, values and beliefs, and to transmit signs of what it is to be human from one generation to the next. They also enable us to see reality from different perspectives where the same image may form a bridge, say, between science and religion. However, an image may also enable us to grasp mysteries beyond human understanding. In meditating on Sutherland’s tapestry one is obviously beginning with messages that may be presented through graphic art. Notions about nature are equally powerful when presented in words and music. In this context, students soon began to move between the different kinds of communication media.

Using a system of ‘notional appraisals’, examples may be gathered within a humanities syllabus of the influential role played by the visual arts, literary expressions, and architecture, in the formation and maintenance of religious and spiritual values. However, there is no generally accepted educational framework for gathering and using neighbourhood notions about nature to link communities and environment to a larger whole. In particular, classroom examples are needed which highlight the use of notional values of environment in guiding the course of local development.

This issue came to a head for many children in South Wales when the super-tanker ‘Sea Empress’ came to grief in Milford Haven in February 1996. SCAN*, the Schools in Communities Agenda 21 Network, was just beginning to develop as a system of environmental appraisal in Pembrokeshire’s schools. Children in the SCAN schools were already alerted to the fragility of their neighbourhood, but the Sea Empress disaster still came as a shock. There was a burst of meditative creative activity as they tried to articulate their feelings of fear and frustration about the loss of valued features of their local coastline. These, for the most part, appeared as meditative poems, letters, and video presentations. There was also a conference in Cardiff”s National Museum led by the Pembrokeshire SCAN schools who were in the front line of the oil spill and its horrific clean-up. The mindmap of this project can be seen at:

http://www.suffolkkemps.info/The%20Great%20Coventry%20Tapestry/index.html

There is also an international educational wiki on living sustainably, currently receiving between 15 and 50 unique visitors per day:

http://livingsustainably.wikispaces.com/home

Meditation on One Square Foot of Earth

Sheila Roberge, is an UNH Cooperative Extension Outside Volunteer. During one class, to push them, and herself, a little harder, she led her students outside and each student measured off one square foot of ground. Each then got down close and looked long and carefully in his or her square foot. They found amazing things. Lots and lots of ants: red ants, black ants and red-and-black ants. Worn-down grass with roots twisted at the surface competed with spindly weeds for a bit of sun and space, and dead pine needles crisscrossed each other, making delicate patterns on the of the ground.

Dried bits of seeds, bark, and tiny twigs filled in spaces, and here and there rocks and stones pushed up through the grey dirt. In some of the squares we found beetles; once someone found a spider with eggs. It seemed that everyone found pieces of acorns or the husks of seeds.They all wrote down our observations of their square foot of earth.

Back inside the classroom, the students read quietly to themselves the poem, “To Look at Any Thing” by John Moffitt, which begins: To look at any thing, If you would know that thing, You must look at it long.

Fig 10 Half a square metre of upper level storm beach, Machynis, Llanelli, Jan 2918

Then for homework, Sheila Roberts asked them to use their observations of their square foot of earth to write a free-verse poem between 10 and 20 lines. When they read their poems to each other, a quiet reverence filled the room. No one laughed or said anything crude or cruel.

Roberge’s message is go outside and, as Moffitt advises, “enter in to the small silences between the leaves.” Let the natural world around you and beneath your feet fill you with wonder. You don’t need to be a poet or a student to learn to have an appreciation for nature. Just imagine all the earth in square feet, imagine all the life teeming within each square foot, and tread carefully.

https://extension.unh.edu/articles/One-Square-Foot-Earth

Someone else who used the one square foot of Earth for meditation was James Thornton, as outlined above. He was seeking a way in which contemplative practices can contribute toward healing the alienation that has divided us from the Earth. His aim was to regain a sense of connection to the whole cosmos, which comes immediately when there is the sense of connection with the living Earth.

Meditating with Images

The history of art is filled with images made for sacred places and artists often attach themselves to places, carving out sacred spaces, and attending to the details of their specific location. Such a place is Hereford Cathedral and such an artist is Tom Denny.

Fig 11 Thom Denney Treherne Window Hereford Cathedral

Denny’s stained glass paintings are meditative windows with which to access the ideas of Thomas Traherne, an English poet, clergyman, theologian, and religious writer. .A great passion depicted in Traherne’s work is his love of nature and the natural world, frequently displayed in a very Romantic treatment of nature that has been described as characteristically pantheist or panentheist. While Traherne credits a divine source for its creation, his praise of nature seems nothing less than what one would expect to find in Thoreau. Many scholars consider Traherne a writer of the sublime, and in his writing he seems to have tried to reclaim the lost appreciation for the natural world, as well as paying tribute to what he knew of in nature that was more powerful than he was. In this sense Traherne seems to have anticipated the Romantic movement more than 130 years before it actually occurred. There is frequent discussion of man’s almost symbiotic relationship with nature, as well as frequent use of “literal setting”, that is, an attempt to faithfully reproduce a sense experience from a given moment, a technique later used frequently by William Wordsworth.

http://digthatpic.wikispaces.com/Thomas+TreherneOut of Focus: Zenic

Fig 12 Mat Collishaw: Burnng Flowers Framed photograph

People think the goal of meditation is to empty the mind. It’s not about clearing the mind; it’s about focusing on one thing. When the mind wanders, the meditation isn’t a failure. Our brain is like a ‘wayward puppy’, out of control. Catching it and putting it back to the object of focus is the meditation. What better way then to meditate on out of focus photographs to plumb the depths of reality. It is our in depth of perception of fragmented images which shapes the concrete layers of reality.

Reviewing the Saatchi exhibition ‘Out of Focus: Photography’ in 2012 Anna MacNay pointed out that nothing at the Saatchi Gallery is ever just about art in the traditional sense,

“ – that is, it’s never just about looking, seeing, and responding aesthetically; there’s always a conceptual element, something clever, something subversive about the works. And this is certainly the case with the current exhibition, Out of Focus, the first major photography show at the gallery in over ten years. Showcasing the work of 38 international artists – for the term “photographer” is too narrow, and alternative suggestions span such neologisms as “photoworkers”, “photoartists”, “camera artists”, and “cross-platform mediators” – old ideas about the “professional” and “amateur” are disregarded, just as are the boundaries between categories such as documentary, fashion, advertising and art”.

http://art-corpus.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/review-of-out-of-focus-photography-at.html

Anders Clausen’s Picture 35 and Green (both 2010) presented screenshots of desktops, both exploiting and satirising digital photography. At the opposite extreme, Matt Collishaw has created a number of monumental black and white and mirrored mosaics, breaking down the images, as he says, like pixels, but simultaneously adopting zenic art forms.

Central to Mat Collishaw’s work are the themes of illusion and desire, which he uses to draw us into a mental arena where everyday images are questioned and broken down for answers.

Spirituality is a way to move beyond the surface understanding of life and to begin to peek into some of the underlying layers. In the context of the art works in the Saatchi exhibition, peeking means meditation. For example, Noémie Goudal’s Les Amants (Cascade) (2009) appears, at first glance, to be a fast flowing waterfall, but, upon closer examination, reveals itself to be a man-made installation of transparent plastic sheeting set in a dry forest. MacNay asks, Is it still beautiful? Do we still stand there in breathtaking awe? Or do only natural realities deserve such a response? Does a created image of a created artefact deserve equivalent reverence?

Poetic Microcosms

Contemplation of a transient microcosm involving a predator and its prey produced the following poem ‘Windhover’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Fig 13 A ‘windhover’

The Hovering

I caught this morning,

Morning’s minion,

Kingdom of daylight’s dauphin,

Dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon,

In his riding of the rolling level

Underneath him steady air,

And striding high there,

How he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing.

The Swooping

In his ecstasy!

Then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend,

The hurl and gliding rebuffed the big wind.

My heart in hiding stirred for a bird,

– the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

The Dropping

Brute beauty and valour and act,

Oh, air, pride, plume, here buckle!

And the fire that breaks from thee then,

A billion times told lovelier, more dangerous,

O my chevalier!

The Killing

No wonder of it:

Shéer plód makes plough down sillion shine,

And blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

Internet References

https://matcollishaw.com/works/

http://www.suffolkkemps.info/The%20Great%20Coventry%20Tapestry/index.html

http://www.zenpaintings.com/stevens.htm

http://www.zenpaintings.com/collecting-new.htm

http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/calligraphy1.shtml

https://www.uni-marburg.de/fb03/ivk/mjr/pdfs/2013/articles/hisamatsu_2013.pdf

https://zenartexperience.com/about/

https://www.bing.com/images/search?q=Students+Walking&FORM=IRIBIP

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-seed/art-meditation_b_1627635.html