1 Bruno Manser’s struggle

In 1984 Bruno Manser travelled to the Malaysian state of Sarawak where he spent six years living with the Penan tribe. He learnt the language and customs of this people, who are the last on the island of Borneo to live exclusively from hunting and gathering. During the time he was there, he saw the living environment of his Penan friends being gradually laid to waste by the logging companies. Bruno supported the Penan in their fight to resist this process of deforestation, carried out with complete contempt for their property rights, and helped them to organise peaceful protests in which they blocked the roads built (illegally) by the logging companies. In the end he was forced to flee Malaysia and was only able to re-enter the country by roundabout means. In Basel he set up the Bruno Manser Fund to support the Penan and other forest peoples. In 1993 he went on a hunger strike in an attempt to halt timber imports from Malaysia, but his campaign failed. Nonetheless, he did succeed in convincing hundreds of Swiss, French and Austrian municipalities to refrain from using wood derived from unethical logging in the construction of their public buildings. In 2000, Bruno Manser tried once again to visit his friends and organise a campaign to alert world public opinion to their plight. It may be that this cost him his life. He has not been seen since 23 May 2000, two days after he crossed the wooded border into Sarawak.

2 Adding a cultural value to trees

It was during Manser’s first year living with the Penan that a joint UNEP international conference published an assessment of the role of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases on climate change and concluded that greenhouse gases were expected to cause significant global warming in the next century. Up until then the only economic value of tropical forest trees was to produce high quality timber to meet the demands of rich Western consumers. In 1997, the value of tropical forests in regulating atmospheric carbon dioxide was part of the discussions which led to the Kyoto Protocol. The talks established legally binding emissions targets for industrialized countries, and created innovative mechanisms to assist these countries in meeting these targets (Fig 1).

Fig 1 Adding value to trees as an ecosystem service

One of these mechanisms is the carbon credit (often called a carbon offset). It is a financial currency that represents a tonne of CO2 (carbon dioxide) or CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent gases) removed or prevented from entering the atmosphere in a carefully designed and managed emission reduction project. Carbon credits can be used, by governments, industry or private individuals to offset carbon emissions that they are generating. Offset schemes vary widely in terms of the cost, though a fairly typical fee would be around £8/$12 for each tonne of CO2 offset. At this price, a typical British family would pay around £45 to neutralise a year’s worth of gas and electricity use, while a return flight from London to San Francisco would clock in at around £20 per ticket.

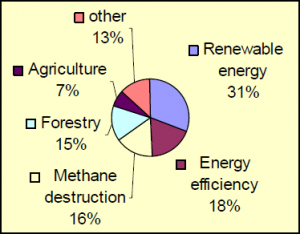

Carbon credits add value to forests and tree planting when they are associated with removing existing CO2 or CO2e emissions from the atmosphere. Afforestation and reforestation activities are now universally accepted as a means by which existing emissions can be removed from the atmosphere and carbon credits can be cashed in by owners of the land on which the project is carried out (Fig 2).

Fig 2 The carbon offset system

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified five stores of carbon biomass, namely the above ground biomass, below-ground biomass, litter, woody debris and soil organic matter. Among all the carbon pools, the above-ground biomass of trees constitutes the major portion of the carbon pool. Estimating the amount of forest biomass is very crucial for monitoring and estimating the amount of carbon that is lost or emitted during deforestation, and it will also give an idea of the potential of trees to sequester and store carbon in the forest ecosystem. In 2000, the IPCC gathered the available evidence for a special report which concluded that tree-planting could sequester (remove from the atmosphere) around 1.1–1.6 GT of CO2 per year. That compares to total global greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to 50 GT of CO2 in 2004. Oliver Rackham, a Cambridge University botanist and landscape historian, describes the problem of carbon credits succinctly: ‘Telling people to plant trees [to solve climate change] is like telling them to drink more water to keep down rising sea levels.’ . On the other hand, giving carbon credits to people living in forested areas is a means of transferring wealth from rich to poor countries.

The mechanism is seen by many as a trailblazer. It is the first global, environmental investment and credit scheme of its kind, providing a standardized emissions offset instrument, the certified emission reduction credit (CER).

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), defined in Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol, allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol (Annex B Party) to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries. Such projects can earn saleable CER credits,which can be counted towards meeting Kyoto targets.

A CDM project activity might involve, for example, a rural electrification project using solar panels or the installation of more energy-efficient boilers. The mechanism stimulates sustainable development and emission reductions, while giving industrialized countries some flexibility in how they meet their emission reduction or limitation targets. A CDM project must provide emission reductions that are additional to what would otherwise have occurred. The projects must qualify through a rigorous and public registration and issuance process. Approval is given by the Designated National Authorities. Public funding for CDM project activities must not result in the diversion of official development assistance.

The mechanism is overseen by the CDM Executive Board, answerable ultimately to the countries that have ratified the Kyoto Protocol. Operational since the beginning of 2006, the mechanism has already registered more than 1,650 projects and is anticipated to produce CERs amounting to more than 2.9 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent in the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, 2008-2012.

As a part of the global carbon market, the voluntary CO2 market is different from the compliance schemes under the Kyoto Protocol and EU-ETS. Instead of undergoing the national approval from the project participants and the registration and verification process from the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), the calculation and the certification of the emission reduction are implemented in accordance with a number of industry-created standards.

The advantage of lower development/transaction cost makes the voluntary market especially attractive to those small and sustainable projects to which the UN certification process is too expensive.

Approximately one third of all greenhouse gases are estimated to be caused from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) activities. These notably include methane emissions from agriculture, but also deforestation and ecosystem degradation.

Deforestation represents the largest source of LULUCF emissions (approximately 18% of total greenhouse gas emissions, as opposed to 13% for agriculture). Yet, the only types of projects that are delivering carbon credits in regulated markets are afforestation and reforestation (A/R) projects in the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). Afforestation refers to tree planting projects in areas where there has not been forest cover in the past 50 years, and reforestation to those projects occurring in areas that were more recently deforested.

Projects that mitigate greenhouse gas emissions by avoiding deforestation and/or ecosystem degradation are currently not eligible for generating carbon credits through the CDM. There are currently 4 afforestation and 14 reforestation projects in the CDM project pipeline and one registered CDM forestry project.

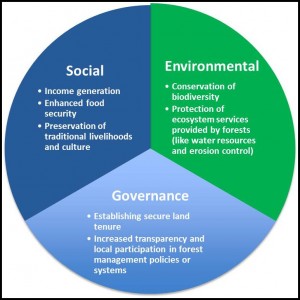

In the voluntary markets for carbon offsets, forestry mitigation projects are more popular investments. Avoided deforestation projects are also allowed as a project option and they account for about 5% [of overall value] and could be significant contributors to the growth of the market (Fig 3).

Fig 3 The voluntary carbon market share by project type (%), as of 2008

However, in terms of overall size the voluntary markets are dwarfed by the CDM. CDM projects hold the lion’s share (approximately 95%) of the global market value of mitigation projects – which is estimated at over $13 billion.. The voluntary market, by comparison is worth approximately $265 million. Forestry investments are estimated to represent about 15% of the voluntary carbon market.

3 REDD

REDD stands for reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and is one of the most controversial issues in the climate change debate. The basic concept is simple: governments, companies or forest owners in the South should be rewarded for keeping their forests instead of cutting them down and so neutralising their carbon footprint.

The idea of making payments to discourage deforestation and forest degradation was discussed in the negotiations leading to the Kyoto Protocol, but it was ultimately rejected as the major economic instrument because of four fundamental issues: ‘leakage’, ‘additionality’, ‘permanence’ and ‘measurement’.

- Leakage refers to the fact that while deforestation might be avoided in one place, the forest destroyers might move to another area of forest or to a different country.

- Additionality refers to the near-impossibility of predicting what might have happened in the absence of the REDD project.

- Permanence refers to the fact that carbon stored in trees is only temporarily stored. All trees eventually die and release the carbon back to the atmosphere.

- Measurement refers to the fact that accurately measuring the amount of carbon stored in forests and forest soils is extremely complex – and prone to large errors.

A general problem is that payments are not for keeping forests, but for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. This opens up the possibility, for example, of logging an area of forest but compensating for the rise in CO2 by planting industrial tree plantations somewhere else.

REDD developed from a proposal in 2005 by a group of countries led by Papua New Guinea calling themselves the Coalition for Rainforest Nations. Two years later, the proposal was taken up at the Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC in Bali (COP-13). In December 2010, at COP-16, REDD formed part of the Cancun Agreements in the Outcome of the Ad Hoc Working Group on long-term Cooperative Action under the Convention.

REDD is described in paragraph 70 of the AWG/LCA outcome:

“Encourages developing country Parties to contribute to mitigation actions in the forest sector by undertaking the following activities, as deemed appropriate by each Party and in accordance with their respective capabilities and national circumstances:

(a) Reducing emissions from deforestation;

(b) Reducing emissions from forest degradation;

(c) Conservation of forest carbon stocks;

(d) Sustainable management of forest;

(e) Enhancement of forest carbon stocks;”

This is REDD-plus (although it is not referred to as such in the AWG/LCA text). Points (a) and (b) refers to REDD. Points (c), (d) and (e) are the “plus” part. But each of these “plus points” has potential drawbacks:

- Conservation in the history of the establishment of third world national parks includes large scale evictions and loss of rights for indigenous peoples and local communities. Almost nowhere in the tropics has strict ‘conservation’ proven to be sustainable. The words “of forest carbon stocks” were added in Cancun. The concern is that forests are viewed simply as stores of carbon rather than ecosystems.

- Sustainable management of forests could include subsidies to industrial-scale commercial logging operations in old-growth forests, indigenous peoples’ territory or in villagers’ community forests.

- Enhancement of forest carbon stocks could result in conversion of land (including forests) to industrial tree plantations, with serious implications for biodiversity, forests and local communities.

There are some safeguards annexed to the AWG/LCA text that may help avoid some of the worst abuses. But the safeguards are weak and are only to be “promoted and supported.” The text only notes that the United Nations “has adopted” the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The text refers to indigenous peoples’ rights, but it does not protect them.

Although much has been written about addressing these issues, they remain serious problems in implementing REDD, both nationally and at a community project level.

There are two basic mechanisms for funding REDD: either from government funds (such as the Norwegian government’s International Forests and Climate Initiative) or from private sources, which would involve treating REDD as a carbon mitigation ‘offset’, and getting polluters to pay to have their continued emissions offset elsewhere through a REDD project. There are many variants and hybrids of these two basic mechanisms, such as generating government-government funds through a “tax” on the sale of carbon credits or other financial transactions.

Trading the carbon stored in forests is particularly controversial for several reasons:

- Carbon trading does not reduce emissions because for every carbon credit sold, there is a buyer. Trading the carbon stored in tropical forests would allow pollution in rich countries to continue, meaning that global warming would continue.

- Carbon trading is likely to create a new bubble of carbon derivatives. There are already extremely complicated carbon derivatives on the market. Adding forest carbon credits to this mix could be disastrous, particularly given the difficulties in measuring the amount of carbon stored in forests.

- Creating a market in REDD carbon credits opens the door to carbon cowboys, or would be carbon traders with little or no experience in forest conservation, who are exploiting local communities and indigenous peoples by persuading them to sign away the rights to the carbon stored in their forests.

4 Community REDD

Because of the serious issues surrounding the value of REDD to community wellbeing, real and imagined, the REDD scheme has been described by its opponents as an example of neocolonialism. Yet many REDD proponents continue to argue that carbon markets are needed to make REDD work. The Environmental Defense Fund, for example, on its website states that,

“Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD), which EDF helped pioneer, is based on establishing economic incentives for people who care for the forest so forests are worth money standing, not just cleared and burned for timber and charcoal. The best way to do this is to allow forest communities and tropical forest nations to sell carbon credits when they can prove they have lowered deforestation below a baseline.”

This is to prioritise ‘pro-poor’ REDD policies and measures. Numerous policies and measures exist to reduce deforestation and degradation (e.g. fire prevention programmes; expanding protected areas; improved law enforcement etc.). Whilst different options may have similar impacts in terms of emissions reductions in any particular area, there could be significant variation in terms of their implications for the poor. The options chosen must first and foremost be based on accurate identification of the drivers of deforestation/degradation, but there must also be a strong political commitment within a framework of cultural ecology to maximise the possible benefits for the poor. In other words, to increase the chances of REDD working for the poor, this must be explicitly recognised in the choice of policies and measures. This was the starting point of the document ‘ Making REDD work for the poor, prepared on behalf of the Poverty Environment Partnership (PEP) in 2008.

The main thrust of the argument was to apply measures to improve the equity of benefit distribution The distribution of benefits from REDD both internationally and within countries is likely to be highly variable due to the design of international systems and the variety of interests of investors (market actors or funders) which will drive investment decisions. For example, finance is likely to go towards ‘low risk’ countries, areas or activities where implementation is most cost effective or that fit internationally established rules, such as those related to the developing baselines. Benefit redistribution mechanisms may be required at international levels and within developing countries. These may include options such as stabilisation funds or preventative credits, provided by international donors to countries with low historical deforestation rates; or levies or taxes placed on market mechanisms within countries that are reinvested into pro-poor policies and measures.

Within the national context, strengthening the role of local governments in benefit distribution and regulation of REDD could also help deliver benefits to the poor. Forest authorities are often one of few government departments with a physical presence in rural areas which can get information to, and receive information from, communities. The private sector could also play a part, for example through providing roles for local government staff in project monitoring and training in technical skills. At local scales and in REDD projects, partnerships between investors and funders could be used to strengthen equitable benefit sharing in REDD schemes, bearing in mind risks related to top down initiatives and asymmetries in information available in their negotiation.

A good example of the application of REDD aimed directly at community benefits is provided by ‘Plan VIVO’s REDD project’ in the Yaeda Valley of Tanzania, where a major aim is to protect the hunter-gatherer cultural heritage of the Hadza people..

An environmental heritage is “all the material and immaterial elements which combine to maintain and develop the identity and autonomy of its ‘proprietor’ in both time and space through a gradually evolving environment”. Henry Ollagnon.

In other words, the heritage does not exist as such in the absence of a property relationship with a “proprietor” who invests in it and manages it. A heritage in which there is no investment, and which is abandoned by its “proprietor”, is a heritage that is falling into ruin and disappearing. This notion is readily understandable in the context of, for example, architectural heritage, when there is someone – owner or just tenant, private or public, individual or collective – who has certain options for managing it, But it is also the case with an ecological heritage, which is the basis of a people’s distinctive culture. Their ecological niche defines their homeland to which they have property rights resulting from a thousand or more years of occupation. Spiritual beliefs of these ‘first peoples’ steer the powers of nature which surround them. Their life is intimately linked to local resources that provide a substantial proportion of energy and protein requirements, as well as most vitamins,essential elements, and minerals. Thus, traditional food is still given a significant place in determining who they are.

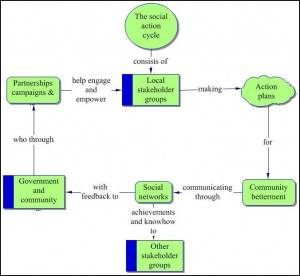

In the global REDD debate, many concerns have been expressed by developing countries, in particular, concerns about the rights of indigenous people and communities dependent on forests and the impact of REDD programmes on such groups. The overwhelming need of communities and people living with trees is to ensure that they are involved in a positive and mutually beneficial way in the management of these resources, since this is one of the very few effective means of controlling deforestation and forest degradation over very large areas. A principle has emerged here. To reduce deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, it is essential to promote solutions involving local people in the sustainable management of forests; and at the same time to link incentive mechanisms with options to improve livelihoods (Fig 4).

Fig 4 Potential community level benefits from the carbon market

The establishment of a community REDD in the Yaeda Valley is one of Plan Vivo’s newest and largest projects, covering over 20,000 hectares of Hazda community land. Plan Vivo is a registered Scottish charity, which has created a set of requirements for smallholders and communities wishing to manage their land more sustainably. Plan Vivo has developed the Plan Vivo Standard, which is a framework for Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes for rural smallholders and communities dependent on natural resources for livelihoods.

The Hadza are an egalitarian society and value their land highly, however getting others to understand this value is not always easy. Creating a ‘real’ economic argument through carbon payments for the ecosystem service that includes biodiversity helps communicate this value as well as supporting the communities who depend on the land. This project will augment the capacities of local forest users for guarding their resources, carrying out forest inventories; monitoring carbon flux; establishing equitable and transparent REDD mechanisms for sharing revenue; and understanding and actively participating in the overall REDD carbon credit process. Already, remarkably, the project has introduced computer skills needed to manage the Hazda heritage to stand alongside the age-old hunter gatherer survival skills.

The essence of the community-led scheme is clear from the following interview with a female coordinator of the Plan Vivo scheme.. Pili Goodo is one of the Carbon Zambia’s coordinators, or animateurs, in Yaeda and as such is responsible for project operations within each village. She compiles the data on land use and poaching brought in by the scouts,represents the project at village meetings and generally acts as the first point of call for any project activities.

She talked to Marc from Carbon Tanzania about how the project has affected her community.

Marc: How has the community been involved in setting up the project?

Pili: Marc came [to a community meeting] to introduce us to this idea of valuing trees because of the carbon inside. We had a lot of questions about how you know that the carbon is in our trees and how people in another country can pay us to help protect our trees and land, why would they do this?

We began to understand how people know about carbon in trees during the tree [above ground biomass] survey where we measured many trees and put the results into a computer. Many of the community were trained during the survey and Carbon Tanzania explained to us using maps and pictures taken from high up that our land is being changed by farmers.

Marc: What have you learned about your natural resources through this project?

Pili: We know that our resources are valuable but how can we make others see that? They want to farm because they don’t know how to live without farming. Now people are seeing us getting money and jobs and want to know how they can get money.

Marc: Why and how did you become involved in the efforts to protect Hadza lands?

Pili: We are all involved! I have secondary education and therefore a better ability to communicate with others like UCRT and Carbon Tanzania… many women will not travel far from their homes but the men can move over a greater distance… [to] do the work of community guards and anti-poaching. We all need to guard our land, without our land we are lost, we can’t be hadza without land, the hadza are part of environment.

Marc: How do these carbon conservation efforts help you and your community?

Pili: Myself and the community guards are all paid directly from the carbon project… I have started a small shop with my money and others buy things from me. The money [paid to the community] is usually spent on school fees, hospital and food. The community sits down and has a meeting to decide what the money should be spent on, we have to document this meeting and send it to Carbon Tanzania, they then put the money into the designated account. In November more of the money is spent on food reserve as it is the end of the dry season and there is very little natural food.

Marc: Why do you feel it’s important for women to work on conservation?

Pili: [Laughs] Why not? … this job is perfect because I am always near my home and everyone can find me to report information.

Pili is one of the local social pillars of the Carbon Zambia action plan, which is an illustration of the way in which environmental improvements, no matter their specific objectives or where they are initiated, are operated as a managed social action cycle (Fig 5).

Fig 5 Managing community betterment

Pili is clearly important as a communicator in the Hazda social betterment cycle. Communication is the key to the robustness and resilience of community projects. To meet this need, PCs, and Internet connections, are becoming more prevalent and more widely adopted in rural communities worldwide. Mobiles have been the dominant technology to date in rural areas, characterised by relatively low adoption costs and flexibility of application. Given the scarcity of alternative communication technologies in Africa (i.e. fixed telephony), and the general lack of infrastructure, ICTs, such as mobiles, have rapidly come to play an important role in rural livelihoods. Increasingly, ICTs have improved rural resilience to external stressors such as climate change: strengthening some aspects of resilience but potentially weakening others. It’s much easier for people to get on with their work when they have a clear idea of what’s expected of them. The role of ICTs in project management is to discipline planning, organizing, and the securing and managing of resources to bring about the successful completion of specific tasks to meet specific goals and objectives. In these respects it can be anticipated that there are going to be developments in ICTs specifically designed for communities aimed at ensuring that there is a clear plan of action, detailing who’s responsible for the work required, when work needs to be delivered, plus any other useful information the project team may need. Above all, ICTs designed for planning and recording have an important role in monitoring outcomes of REDD community projects.

Would REDD have made Bruno Manser’s struggle against top-down commercial deforestation any easier?. Without monitoring enforceable safeguards, and strict controls and regulation through measurable performance indicators, REDD may deepen the woes of developing countries: providing a vast pool of unaccountable money which corrupt interests will prey upon and political elites will use to extend and deepen their power, becoming progressively less accountable to their people. In the same way that revenues from oil, gold, diamond and other mineral reserves have fuelled pervasive corruption and bad governance in many tropical countries, without public transparency REDD could prove to be another ‘resources curse’. Ultimately, this will make protection of forests and their communities less likely to be achieved and will do nothing to ameliorate carbon emissions.

5 Internet references

Trees: between nature and culture

http://coe.archivalware.co.uk/awweb/pdfopener?smd=1&md=1&did=594700

REDD Schemes

http://www.redd-monitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/08-10_REDD_An_Introduction.pdf

http://www.un-redd.org/Stakeholder_Engagement/Community-BasedREDDCBR/tabid/1058797/Default.aspx

http://www.e-mfp.eu/sites/default/files/resources/2014/02/European_Dialogue_No.6.pdf

Plan VIVO

http://www.planvivo.org/about-plan-vivo/

Plan VIVO Tanzania

Making REDD work for the poor

http://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/3451.pdf

A complete guide to carbon offsetting

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/sep/16/carbon-offset-projects-carbon-emissions

Benchmarking rural resilience

http://www.niccd.org/sites/default/files/RABIT%20Uganda%20Short%20Case%20Study%20e-Resilience.pdf