“Every phase of life in the countryside contributes to the existence of cities. What the shepherd, the woodman, and the miner know, becomes transformed and ‘etherealized’ through the city into durable elements in the human heritage: the textiles and butter of one, the moats and dams and wooden pipes and lathes of another, the metals and jewels of the third, are finally converted into instruments of urban living: underpinning the city’s economic existence, contributing art and wisdom to its daily routine. Within the city the essence of each type of soil and labor and economic goal is concentrated, thus arise greater possibilities for interchange and for new combinations not given in the isolation of their original habitats.” (Lewis Mumford: The Culture of Cities, 1938)

Creation on Earth is in crisis. Why then do we in the West continue in activities that are manifestly harmful to our lives, other peoples and other beings of the natural world? A large part of the answer is that we do not want to lose the comforts that we few hundreds of millions enjoy, which are bought at the cost to the illiterate billions who we know cannot rise to our life styles. At the centre of our behaviour is the fundamental principle of ecological territoriality that is common to all life forms. With respect to human primates, this principle puts land at the heart of survival, first as hunter-gatherers meeting family needs, now as consumers of the products from the lesser economies of far distant places to satisfy our social wants. As a distinct body of knowledge, land and the ways that it is incorporated into culture for production defines the subject of natural economy.

What follows was written as an introduction to natural economy as a distinct body of knowledge, which in the 1980s was the first new school subject introduced into the UK examination system since the Victorian era. But it never caught on. The essay was written to raise the question posed above, and to point out that it was actually raised and answered at the very beginnings of industrialism. The answer then was that we require a value-based national curriculum, which cuts across specialized subject boundaries in order to wean ourselves off the ideology that we should live as if we could liberate ourselves from the bounds of nature. 1 Natural Economy In his book, Land and Market, published in 1991, Charles Sellers describes the America of 1815, on the eve of a postwar boom that would “ignite a generation of conflict over the republic’s destiny.

” Conflict between east and west, rural and urban, Native- and Euro-American, even farmer and wife, that resulted as “history’s most revolutionary force, the capitalist market, was wresting the American future from history’s most conservative force, the land.”

Sellers describes a series of interactions between humans and the land, beginning with the subsistence economy of Native Americans. They were supplanted by Euro-American farmers who, in bringing their own village economy to the hinterlands, created an “intermediate subsistence culture.” In time, that culture fell prey to the wider market, in part because wheat and cotton booms made it profitable for inland farmers to grow and transport surplus crops to expanding urban markets. The outcome was that, eventually, the subsistence farming culture ran out of the cheap land it needed to maintain a reserve of production in order to sustain the family enterprises from one generation to the next.

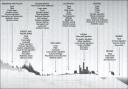

We are now well into the era of rural depopulation, which was starting to spread worldwide at the when Sellers was writing. By the 1980s it had became clear to some educators that there was a need for a new subject dealing with the rapid pace of global urbanization. This marked the shifting power of production from the land to global business conglomerates. In particular, the international division of the University of Cambridge Local Examination Syndicate took the view that it was urgent to promote a school syllabus, which addressed the drivers of industrialism from which our ecological ills arise. The UCLES subject was called ‘natural economy’ because the knowledge framework we need has to deal with how biophysical resources of the planetary economy are organised for production. Therefore, education has to be concerned with how the environmental impact of industrialism, and its sub-system of global consumerism, may be resolved for sustainable development. Natural economy complements the subject of ‘political economy’, which deals with how human societies are organised for production. It is linked to it through value systems; i.e. the notional economy, based on the flow of mental energy as ideas and beliefs about how society should be ordered for the good-life we define as living sustainably (Fig 1).

Fig 1 A mind map of natural economy

Natural economy was designed by Cambridge teachers as a cross-curricular knowledge system, which requires teaching resources that are holistic, and exemplify the imaginative leaps across subject boundaries necessary to put short-term plans in the long term perspective of sustainable development. The term ‘polymath’ describes people who have the mental ability to make such connections. The other requirement is that the subject and its exemplars should be presented in a style that allows pupils to navigate effortlessly through a sea of detail. An interactive mind map format is essential to command a full understanding of natural economy and its applications to environmental management. It is also essential to have social models of the past, which continue to echo through the ages, in order to understand current issues of the relationships of people and land. For example, there is much fear around regeneration in ordinary communities because of past models such as the Highland Clearances that had no regard for the ordinary people that would be displaced and were driven on a class agenda. A century or so later, the Scottish Slum Clearances that, though well intentioned, broke up the connectiveness of families, neighbourhoods, societies, clubs, brass bands, orchestra’s etc and left a remnant of misery that led to siege mentality, crime and anti-social behaviour.

2 Land for the few

What became known historically as the ‘Clearances’ were considered by 18th century Scottish landlords as necessary “improvements” to their landed estates. The social upheaval is now regarded as an international model of social injustice and ethnic cleansing. As the outcome of the relationship of the Scottish elite with their hereditary tribal lands, the clearances are thought to have been begun by Admiral John Ross of Balnagowan Castle in Scotland in 1762. Actually, MacLeod Chief of the Clan MacLeod, had begun experimental work on Skye in 1732. Chiefs engaged Lowland, or sometimes English, managers with expertise in more profitable sheep farming, and they “encouraged”, often forcibly, the population to move off suitable land, which was given over to sheep pasture. A wave of mass emigration from the land came in 1792, known as the “Year of the Sheep” to Scottish Highlanders. The dispossessed tenants were accommodated in poor crofts or small farms in coastal areas where farming could not sustain the communities and they were expected to take up fishing. It is said that in the village of Badbea in Caithness the conditions were so harsh that, while the women worked, they had to tether their livestock and even their children to rocks or posts to prevent them being blown over the cliffs. Others were put directly onto emigration ships to Nova Scotia, the Kingston area of Ontario and the Carolinas of the American colonies. There may have been a religious element in these forced removals since many Highlanders were Roman Catholic. This is reflected by the majority representation of Catholics in areas and towns of Nova Scotia such as Antigonish and Cape Breton. However almost all of the very large movement of Highland settlers to the Cape Fear region of North Carolina were Presbyterian, which is evidenced even today in the presence and extent of Presbyterian congregations and adherents in the region.

In 1807 Elizabeth Gordon, 19th Countess of Sutherland, touring her inheritance with her husband Lord Stafford (later made Duke of Sutherland), wrote that “he is seized as much as I am with the rage of improvements, and we both turn our attention with the greatest of energy to turnips”. As well as turning land over to sheep farming, Stafford planned to invest in creating a coal-pit, saltpans, brick and tile works and herring fisheries. That year his agents began the evictions, and 90 families were forced to leave their crops in the ground and move their cattle, furniture and timbers to the land they were offered 20 miles away on the coast, living in the open until they had built themselves new houses. Stafford’s first Commissioner, William Young, arrived in 1809, and soon engaged Patrick Sellar as his factor who pressed ahead with the process while acquiring sheep farming estates for himself. Elsewhere, the flamboyant Alexander Ranaldson MacDonell of Glengarry portrayed himself as the last genuine specimen of the true Highland Chief while his tenants were subjected to a process of relentless eviction. To landlords, “improvement” and “clearance” did not necessarily mean depopulation. At least until the 1820s, when there were steep falls in the price of kelp, landlords wanted to create pools of cheap or virtually free labour, supplied by families subsisting in new crofting townships. Kelp collection and processing was a very profitable way for local landlords to use this labour, and they petitioned successfully for legislation designed to stop emigration. This took the form of the Passenger Vessels Act 1803. Attitudes changed during the 1820s and, for many landlords, the potato famine, which began in 1846, became another reason for encouraging or forcing emigration and depopulation.

According to Tom Devine, who wrote up this episode in Scottish history, it is hardly surprising in view of these self-interest developments, that the first official survey of landownership, conducted by the government in 1872-3, confirmed that the historic Scottish structure remained intact. Some 659 individuals owned 80 percent of Scotland, while 118 held 50 percent of the land. Among the most extraordinary agglomerations were those of the Duke of Sutherland. who possessed over 1 million acres, the Duke of Buccleuch with 433,000 acres, the Duke of Richmond and Gordon 280,000 acres and the Duke of Fife 249,000 acres. As in the Highlands, the wealthy of the towns were acquiring Lowland estates throughout this period. Yet this process had not reversed the 18th century pattern whereby the properties of greater landowners grew while those of the small lairds declined further. Studies of the land market in Aberdeenshire suggest that only a relatively small proportion of territory (less than 15 percent of the total acreage) was bought by new families in the 19th century. Most of these sales were of property belonging to previous incomers rather than traditional owners. Throughout most of the Lowlands, therefore, the territorial ascendancy of the most powerful families, who possessed huge estates running into many thousands of acres, remained inviolate. Buccleuch, Seafield, Atholl, Roxburgh, Hamilton and Dalhousie, to name but a few of the greatest aristocratic dynasties, still controlled massive empires. Scotland, had the most concentrated pattern of private landownership in Europe, even more so than in England, where the territorial power of the landed aristocracy was also unusually great by comparison with other nations.

A full century after the Industrial Revolution no economic or social group had yet emerged to challenge this mighty elite. Great industrial dynasties such as the Coats, Tennant and Baird families did buy into the land, but their total possessions were miniscule compared to those of the hereditary landowners, while their deep interest in acquiring landed property was itself a confirmation of its continuing attraction and significance Landowners in this period did not simply gain from the swelling rent rolls as grain and cattle prices rose steadily and investment in land bore profitable fruit. Industrialisation also contributed handsomely to the fortunes of several magnates by affording them the opportunity to exploit mineral royalties. Among the most fortunate Scottish grandees in this respect was the Duke of Hamilton, whose lands included some of the richest coal measures in Lanarkshire, the Duke of Fife, the Earl of Eglinton and the Duke of Portland. Landowners were heavily involved in railway financing and, indeed, before 1860 were second only to urban merchants as investors in the new transport projects. Some patrician families also benefited from considerable injections of capital from the empire to which the landed classes often had privileged access through their background and the associated network of personal relationships and connections. In the north-east, for instance, one conspicuous example of the lucrative marriage between imperial profits and traditional landownership was the Forbes family of Newe. They had owned the estate since the 16th century but its economic position was mightily strengthened and its territory increased from the middle decades of the 18th century when the kindred of the family began merchanting in India. By the early 19th century the House of Forbes in Bombay was producing a flow of funds for a new countryseat, enormous land improvements and the purchase of neighbouring properties in Aberdeenshire. Examples of the connection between imperial profit and landownership of the kind illustrated by the Forbes family could be found in every county of Scotland.

Another important dimension is the extension of the grip of the Scottish aristocracy into England. Two prominent families are the Crichton-Stuarts and the Douglas-Hamiltons, The former as the 1nd Marquis of Bute, married into the Windsor family of South Wales. His son developed the Windsor’s mineral estate based on the lordship of Cardiff Castle; his grandson, become the richest man in Europe on coal and property revenues. This fortune was achieved through controlling the world’s supply of coal from mines in the South Wales valleys and the docks built on the marshy waste surrounding Cardiff Bay. The Douglas-Hamiltons, in the person of the Duke of Hamilton, based on the Isle of Arran and the Borders, acquired an estate in three Suffolk villages, from which he was able to participate in English political system through a seat in the House of Lords as Duke of Brandon and Hamilton.

3 Land for everybody

The Highland Clearances were just one example of the land issues of natural economy that came to a head in the United Kingdom during the 19th century. These issues centre on the proposition that land is in limited supply with respect to everyone who, from planner, to rambler, wishes to partake of it as ‘a good’. Three outstanding polymaths, whose lives and writings span the rise of the land issue and who commented forcibly upon it in England, are Charles Kingsley, John Ruskin, and Henry Rider Haggard. They were part of a counter movement to the economic forces of industrialism, which is illustrated by their lives and writings, Kingsley was an urban reformer, very much concerned in his novels, lectures and tracts, with relieving the ills of the urban masses that had migrated from the countryside. He was a Darwinian and enthusiast of applied science. Ruskin was a powerful educator who, in his writing on social reform, deplored the crushing influence of industrialism on art, morality, and the natural world. He saw the ‘land question’ as a matter of rapid population growth. Haggard was a rural reformer, who wrote with personal experience about land conflicts in the colonies, and the drift of people from the land. His diary of 1898 is a vivid month-by-month account of the life of a progressive farmer involved with the social problems of village, county, and the national scene. His fiction, about upper-class Englishmen adventuring abroad, reveals the mind-match that is possible between individuals of different lands, usually through a potent atmosphere of intrigue, violence and romance.

A Victorian knowledge system cannot avoid incorporating spiritual notions that provided the 19th century drive and justification for social change. In particular, the Victorians found themselves caught within a Biblical worldview of the origins and purposes of human existence. In this sense, religious belief was at the heart of all environmental problems, issues and controversies. John Ruskin’s writings are what we would now describe as a cross-curricular attempt to encompass the notional, utilitarian, and academic ideas about how we should value and use natural resources. His personal synthesis of religion and natural resources exemplifies the unusual breadth and depth needed to clarify and deepen our values and actions to meet today’s challenges of sustainable development. Ruskin’s standpoint was to interpret God’s plan for humanity, as set out in the Book of Genesis, in terms of the Creator giving Earth substance and form. God willed functions into natural resources so that they may be used by His people to fulfill their divine destiny. He embedded in nature a divine blueprint for a natural economy, which organises the use of nature for production in conjunction with a local political economy dispensing justice for rich and poor alike. The necessary materials and energy were provided, as physical and biological resources, through planetary and solar economies. The former produces episodes of mountain building associated with Earth’s molten core; the latter governs weather and climate. These flows of materials and energy were set in motion following God’s ‘command that the waters should be gathered’, which produced the planet’s land-sea interactions. At this point Ruskin, envisaged the Creator’s blueprint being realised through the denudation of mountains by rainfall. Starting from the divine ‘gathering of waters’ the human natural economy was dependent on the God-given ‘frailness of mountains’.

The first, and the most important, reason for the frailness of mountains is “that successive soils might be supplied to the plains . . . and that men might be furnished with a material for their works of architecture and sculpture, at once soft enough to be subdued, and hard enough to be preserved; the second, that some sense of danger might always be connected with the most precipitous forms, and thus increase their sublimity; and the third, that a subject of perpetual interest might be opened to the human mind in observing the changes of form brought about by time on these monuments of creation”. (6.I34-35)

This quotation may be taken as an example of Ruskin’s philosophy that environmental features produce ideas, which are then confirmed by studying the features themselves. Ruskin’s holistic knowledge system relates human spiritual values of the Bible to our attitudes to, and use of, the land (Fig 2). For example, the Old Testament has several references concerned with the fruitfulness and flourishing of the planetary economy linked with ‘the finest produce of the ancient mountains and the abundance of the everlasting hills’. Other Victorian thinkers tended to slot into this framework.

Kingsley and Haggard differed from Ruskin by giving more value to the processes and fruits of science, particularly as applied to industrialism. Charles Kingsley for example, was one of the first to articulate the science of ecology. He also probed into freshwater and marine biology, and was deeply involved with public health issues concerning the supply of clean water to disease-ridden towns and cities. Rider Haggard was personally involved with the more efficient use of land for agricultural production and forestry, subjects on which Ruskin had little to say. All three made practical proposals for social change to improve the lot of artisans and their families.

Fig 2a Ruskin’s natural economy

“And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called the Seas.” (Genesis 1:9-10)

Fig 2b Natural economy according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment http://maweb.org/en/index.aspx

The concept of land was approached by Victorian educators through five cultural ideologies (systems), and fourteen associated behaviours (processes), which still facilitate social change.

Land Processes

1 Annexation of land

2 Attachment to land

3 Conservation of land

4 Depiction of the land

5 Cession of land

6 Conquest of land

7 Enhancement of land

8 Eviction from the land

9 Exclusion from land

10 Exploitation of land

11 Migration from the land

12 Reclamation of land

13 Rights to land

14 Settlement of land

Land systems 1

Agrarianism

2 Colonialism

3 Environmentalism

4 Ethnicism

4 Land systems

Ethnicism We emerged as a ‘human’ species through a system of ethnoecology, which involved the integration of family groups with seasonal cycles of biological production. As hunter-gatherers, we first developed ethnic skills to adapt our basic needs to the pace of local ecological production, and its vagaries of climate and terrain.

Agrarianism The advent of agriculture transformed our relationships with natural resources. Nature was equated with ‘land’, which became a focus of possession through settlement, and alteration through cultivation, and the selective breeding of crops and livestock.

Colonialism Colonialism has always been a foundation of economic development wherever a settled society could command foreign lands, and, or, their people, to produce raw materials for home consumption. Land became ‘territory’, and the means of domination were always the same, the fleet, the army, violence and, if necessary cunning and even treachery. Colonialism, and its ultimate development, through conquest, as imperialism, are as old as history, and have carried world development along in their wake for the past 5000 years.

Industrialism Industrialism was brought about by capital investment in factories and machines, fed by large stocks of natural resources, tended by a stable, dense population, with assured routes to consumers who wanted mass produced goods. The pace of urbanisation was vastly increased by the global spread of industrialism during the last two centuries. There is no country on earth that has not experienced the flood of rural people into towns and cities, lured by visions of partaking of industrialism’s apparently limitless wealth. Land upon which towns and cities were built has a uniformity that generated a culture of ‘placelessness’. Land, which supported industrialised agrarianism, became ‘countryside’. Town and country have distinct cultures despite modern mass communications, which are sometimes nationally divisive. However, ‘placelessness’ is universal because in both cultures it is common for families not to have any connections with the social and spiritual roots of the land upon which their dwelling is built.

Environmentalism One of the most important ethical questions raised in the past few decades has been whether nature has an order, or pattern, that we are bound to understand, respect, and preserve. This is the question prompting the environmentalist movement. Those who answer “yes’ also believe that such an order gives an intrinsic value that can exist independently of us; it is not something that we merely bestow. ‘Reactive environmentalism’ sees environmental problems, issues and challenges as mistakes arising from ignorance foolishness or venality, and regards their solution as increased governmental regulation, and application of expertise to industrialism. ‘Ecological environmentalism’ conceives the problems as being culturally interconnected, and rooted in more fundamental mistakes in the structure of social decision making. Ecological environmentalists judge that major social changes are necessary to resolve ecological problems that if unchecked will be socially destructive. ‘Moral environmentalism’ seeks justification, through Darwinism, as to how we should live. Morality evolves into something more than usefulness and expediency. It becomes a self-transcending sense of mercy, sympathy, and kinship with all animate existence, including Earth itself, and focuses on questions, such as ‘By what right do we elbow aside countless species in our pursuit of resources, and presume to remake nature according to the desires of just one of its life forms?

Conquest Involves aggression activated by kinship, political ideology, and emotional responses to the behaviour of other groups and individuals, exemplified by ‘revenge’, ‘fear’, and ‘covetousness’.

5 Lives and lands

Ruskin and Kingsley were born in the same year, 1819, on the threshold of Victoria’s accession. Ruskin lived a quarter of a century longer than Kingsley, but had completed his major works by the time Kingsley died. In this perspective both writers were dealing with the problems issues and challenges brought about by unprecedented economic, social and scientific changes. Rider Haggard, was born a few years after the great 1851 showcase of British industrial achievement displayed in the Crystal Palace, and his life followed this same historical trajectory. But, by 1860s, there were many signs that while sure of the past, people were becoming increasingly less optimistic about the future. Haggard arrived in Cape Town six months after Kingsley’s death, uncertain of his duties, but determined to make success of his opportunity to participate in the colonial administration of Natal province. As it turned out, although only there a few years, he was witness to what turned out to be the beginning of a loss of confidence in the Empire builders, which in South Africa led to the Boer War of 1899. We can place Haggard in the context of a continuity of generations from his boyhood in country society at the peak of the English squirearchy. His mother’s writings were about the uncertainties of belief brought about by Darwinism. The diaries of his daughter record the impact of the Second World War on village life. In these three lives of one family we have a remarkable view of a century of social change.

Eversley

” I firmly believe, in the magnetic effect of the place where one has been bred; and have continually the true ‘heimweh ‘ home-sickness of the Swiss and Highlanders. The thought of the West Country will make me burst into tears at any moment. Wherever I am it always hangs before my imagination as home, and I feel myself a stranger and a sojourner in a foreign land the moment I get east of Taunton Dean, on the Mendips. It may be fancy, but it is most real, and practical, as many fancies are.”

When he wrote this, Charles Kingsley was thinking about Devonshire, a notional attachment to land, which began in a real sense at Holne vicarage under the brow of Dartmoor, where he was born on 12th June 1819. This deep feeling for the hills, rivers and rocky coastline of the West Country was reinforced from1830, when his father was presented with the rectory of the tiny fishing community of Clovelly. In between, and up to the age of 12, thirsty for knowledge, he was further magnetised by the large skies and luxuriant wildlife of fenland, to the east of Barnack, where his father held the living for six years. However, without doubt, Kingsley’s ‘homeland’ was the village of Eversley and its surrounding Surrey heaths. Here he began married life, little thinking that, with a short interval, it would be his home for thirty-three years. Here he applied his mind to heathland ecology, freshwater biology, and his life-long sport of stream fishing. He died at Eversley on 23rd January 1875.

His relatively brief contact with the fens came out later in descriptions of what was in his boyhood something of a watery wilderness, although fast disappearing through the final stages of agricultural improvement through vast land drainage schemes. These youthful contacts with dykes and bogs were eventually synthesised with a strong sense of English history to author ‘Hereward the Wake’. Clovelly and its surrounding heritage of Elizabethan seafaring produced ‘Westward Ho!’ and evoked an abiding interest in marine biology. However, it was his day to day contacts with the lanes, fields and commons of Eversley that set him thinking about the geological forces that mould the nooks and crannies of a neighbourhood, and determine the development of its small-scale, and sometimes special, pattern of plants and animals.

As Kingsley’s own educational model of a river system, his book, ‘Water Babies’, incorporates all these points of view. Within a compressed industrial landscape the story expresses a biological and moral quest, which is literally carried along in the flow of a river system, from untainted uplands, supplying water power to northern mills, through an urbanised estuary, into a vast imaginary undersea world, as yet unaffected by industrial development. ConistonJohn Ruskin lived for 23 years in a country house, with its stunning mountain views to the West over Coniston Lake, from 1877 to his death in 1900. In a lecture to the people of Kendal in 1877 he described his attachment to the Lake District as follows:-

“Mountains are to the rest of the body of the earth, what violent muscular action is to the body of man. The muscles and tendons of its anatomy are, in the mountain, brought out with force and convulsive energy, full of expression, passion, and strength.”

“I knew mountains long before I knew pictures; and these mountains of yours, before any other mountains. From this town of Kendal, I went as a child, to the first joyful excursions among the Cumberland lakes, which formed my love of landscape and of painting: and now being an old man (he was 58 years old), I find myself more and more glad to return.”

His other ‘home’ was the Swiss Alps, and his purchase of the lakeside estate of Brantwood in the Lake District was a logical decision about the question of where to spend the rest of his life, Switzerland or Cumbria? Both lands focused his mind on two problems; the geological forces that produce cataclysmic upheavals in Earth’s surface, and the artistic depiction of mountains as landscape. He saw these fundamental questions, one of science, and the other of art, as two sides of the same coin. One aspect of his lateral thinking was to connect them through the budding science of meteorology, which had begun to classify weather patterns using the shapes and distribution of clouds. In this context, Ruskin was fascinated by the beauty of ever-changing mountain skies, which has a complex physical basis in the vertical temperature gradients and the relative instability of air flows.

Ditchingham

Rider Haggard had an even longer attachment to a particular part of the English countryside than either Ruskin or Kingsley. Part of his wife’s legacy was a substantial country house in the village of Ditchingham. This community is situated on the northern bank of the River Waveney, which here forms the boundary between Norfolk and Suffolk. Across the river to the south is the Suffolk market town of Bungay. Ditchingham House was his home from 1887 until his death in 1925. His ashes were interred in the village church, and we can do no better than refer to the symbolism of his stained glass memorial, dedicated by his youngest daughter Lilias, as a window on his life.

The subject of the centre light is the crowned and risen Christ bearing in His hand the world showing eastern hemisphere. On the pallium over his robe are seen the Serpent round the Cross, signifying the Crucifixion, the Keys of Life and Death, Adam and Eve denoting Original Sin and the need of Redemption and the Pelican symbol of Love and Sacrifice. On the left is St Michael, Angel of the Resurrection holding the Scales of Justice and a Flaming Sward. On the right is St Raphael, Angel of all Travellers bearing his Staff and girded for a Journey. Below in the centre is a view of Bungay from the Vineyard Hills. On the left, the Pyramids and the River Nile, surrounded by the Lotus Flower emblem of Egypt. On the right, Hilldrop, Sir Rider’s farm in South Africa. These views he loved and they illustrate three sides of his life, Rural, Creative and Imperial.

Above in the upper lights are seen the Chalice, his Crests and Mottoes, and the Flame of Inspiration. In the borders the Open Book, the Crossed Pick and Shovel and various Egyptian symbols, also Oak for strength, Laurel for fame and Bay for victory.

Ditchingham and its neighbouring villages are metaphors for the fundamental aspect of the land question, which starts and finishes by way of arbitration of ‘how much belongs to whom’. This question was literally lived out on a boundary commemorating the disputed territory of two Saxon clans; the ‘North’ and ‘South’ folk. Each tribe claimed descent from the East Anglian ‘kings’ whose Continental ancestors sailed up the shallow estuaries of East Anglia. Small-scale family feuds are written in the tortuous parish boundaries, which snake off in all directions around the parish church. From his agrarian base, amidst the flinty fields at the edge of the ice-eroded East Anglian clay plateau, Haggard takes us via a ‘good read’ on real and imaginative excursions into the many facets of human nature associated with natural and political economy. Through his factual reports, and the characters of his fiction, we may interact with the lives of farm workers, see the machinations of colonial land administrators laid bare, sympathise with the victims of British imperialism, and enter alternative civilisations powered by supernatural forces. In this context, his life is an extraordinary effort to come to grips with the transiency of civilisations, and the individual lives that produce its cultures. Like Ruskin, but in his own way, he was using the gift of a powerful imagination to explore the ordering of human nature for a just and prosperous society, against the background of an apparently indifferent Universe. He proposed practical social reforms to cope with the former, which required political will to enforce. Till the end he thought the power of imagination might reveal invisible strands of immortality connecting the material cosmos with an infinite spiritual structure. Individuals, like himself, with this exceptional power, would be the gatekeepers who could, for good or evil, draw aside ‘the curtain of the unseen’. We can see something of his wide ranging mind in the following quotations from his writings.

Migration

“A still greater matter is the desertion of the land by the labourer. To my mind, under present conditions which make any considerable rise in wages impossible, that problem can only be solved by giving to the peasant, through State aid or otherwise, the opportunity of transforming himself into a small landowner, should he desire to do so, and thus interesting him permanently in the soil as one of its proprietors. But to own acres is useless unless their produce can be disposed of at a living profit, which nowadays, in many instances, at any rate in our Eastern counties, is often difficult, if not impossible. Will steps ever be taken sufficient to bring the people back upon the land; and to mitigate the severity of the economic and other circumstances which afflict country dwellers in Great Britain to such a reasonable extent that those who are fit and industrious can once more be enabled to live in comfort from its fruits. In this question with its answer lies the secret, and, as I think, the possible solution of most of our agricultural troubles. But to me that answer is a thrice-sealed book. I cannot look into the future or prophesy its developments. Who lives will see; these things must go as they are fated-here I bid them farewell.”31 Dec 1898

Emigration

“What I do hold a brief for, what I do venture to preach to almost every class, and especially the gentle-bred, is emigration. Why should people continue to be cooped up in this narrow country, living generally upon insufficient means, when yonder their feet might be set in so large a room? Why do they not journey to where families can be brought into the world without the terror that if this happens they will starve or drag their parents down to the dirt; to where the individual may assert himself and find room to develop his own character, instead of being crushed in the mould of custom till, outwardly at any rate, he is as like his fellows as one brick is like to the others in a wall ?” “Here, too, unless he be endowed by nature with great ability, abnormal powers of work, and an iron constitution, or, failing these, with pre-eminent advantages of birth or wealth, the human item has about as much chance of rising as the brick at the bottom has of climbing to the top of the wall, for the weight of the thousands above keep him down, and the conventions of a crowded and ancient country tie his hands and fetter his thought. But in those new homes across the seas it is different, for there he can draw nearer to nature, and, though the advantages of civilisation remain unforfeited, to the happier conditions of the simple uncomplicated man. There, if he be of gentle birth, his sons may go to work among the cattle without losing caste, instead of being called upon to begin where their father left off; there his daughters will marry and help to build up some great empire of the future, instead of dying single in a land where women are too many and marriage is becoming more and more a luxury for the rich. Decidedly emigration, not to our over peopled towns, but to the Antipodes, has its advantages, and if I were young again, I would practice what I preach. Nov 18″

Exclusion

“Of late years there has been a great outcry about the closing of some of the Norfolk Broads to the public, and the claim advanced by their owners to exclusive sporting rights upon them. Doubtless in some cases it has seemed a hard thing that people should be prevented from doing what they have done for years without active interference on the part of the proprietor. But, on the other hand, it must be remembered that it is only recently the rush of tourists to the Norfolk Broads has begun. It is one thing to allow a few local fishermen or gunners to catch pike or bag an occasional wild fowl, and quite another to have hundreds of people whipping the waters or shooting at every living thing, not excluding the tame ducks and swans. For my part I am glad that the owners have succeeded in many instances, though at the cost of some odium, in keeping the Broads quiet, and especially the smaller ones like Benacre, because if they had failed in this most of the rare birds would be driven away from Norfolk, where they will now remain to be a joy to all lovers of Nature and wild things. These remarks, I admit, however, should scarcely lie in my mouth when speaking of Benacre, since on our return towards the beach, after rambling round the foot of the mere, we found ourselves confronted with sundry placards breathing vengeance upon trespassers, warnings, it would seem, which we had contemptuously ignored. Should these lines ever come under the notice of the tenant of that beautiful place, I trust that he will accept my apologies, and for this once ‘ let me off with a caution.'”HRH May 31st 1898

6 Conclusion

Why did not these lessons of social injustice and the anti-industrialism polemics of influential Victorian writers feed into the education system? The answer also chimes with the failure of natural economy in the 1980s to replace geography and biology in a national curriculum. Although at that time the UK education system was in the throes of reform, which actually, and for the first time, did produce a national curriculum, it was part and parcel of the Thatcherite ideology. The needs for an ecological of the ‘good life’ ran up against values that drove the political economy, which were, as now, the need for maintaining year on year economic growth. Values for living sustainably have to be adopted politically before the education system will change to support the new ideology.

The idea that pieces of non-human nature can be owned is so obvious within industrial cultures that it is still hard to call into question, yet it has not been so apparent to many other peoples. The Native Americans of New England, for example, had quite different conceptions of property than those of the colonists coming from England. We can contrast the specialised subject teaching required by 19th century European Empire builders with the teaching of the native Americans, who were living with no concept of economic growth but in thrall to ecological principles, which will eventually catch up with the West. The Native Americans recognised the right to use a place at a specific time. What was “owned”, was only the crops grown or the berries picked. Thus, different groups of people could have different claims on the same tract of land depending on how they used it. Such rights of use did not allow for the sale of property These differences remain to this day. As Buffalo Tiger, a Miccosukee Seminole Indian stated recently

“We Indian people are not supposed to say, ‘This land is mine’. We only use it. It is the white man who buys land and puts a fence around it. Indians are not supposed to do that, because the land belongs to all Indians, it belongs to God, as you call it. The land is a part of our body, and we are a part of the land. We do not want to ‘improve’ our land; we just wish to keep it as it is. It’s hard for us to come to terms with the white man because our philosophy is so different. We think the land is there for everyone to use, the way our hand is there, a part of our own body.”

Jimmie Durham, a Cherokee, comments similarly

“We cannot separate our place on earth from our lives on the earth nor from our vision nor our meaning as a people. We are taught from childhood that the animals and even the trees and plants that we share a place with, are our brothers and sisters So when we speak of land, we are not speaking of property, territory, or even a piece of ground upon which our houses sit and our crops are grown. We are speaking of something truly sacred.”

Even if nonhuman nature is regarded as the sort of thing, which can be owned, how can it be owned privately? How can one person take claim to land or other parts of nature? By what right does one person exclude others from parts of the earth? If it was not created by those who claim to own it, how can such a claim be legitimate? Although private ownership of the earth is now a common dogma, it was not at the outset of the capitalistic regime. Then the conception of nature as privately owned required justification. Until institutions change to mirror better the economy of the biosphere and its interconnected human values, an appropriate value-based national/international curriculum will never take its place as major subject.

Schools as institutions only mirror and complement the world within which they operate. Therefore, natural economy and similar holistic educational innovations will become institutionalized only when culture is not compartmented into the specialities and disciplines deemed necessary to support year on year economic growth. In the meantime, cross-curricular polymath education has a home within the Internet. For example, the University of East London, ‘virtual schools’ initiative was launched in 2007 to weave the theme of Global Dimension into secondary teacher training to educate for sustainability. Regarding natural economy, this is the central theme for a mind map of cultural ecology (www.culturalecology.info) and is being developed as an e-learning programme for learning about keeping within Earth’s limits.